Posterity and the Future Historian

Highly conscious of their contribution to posterity, many of the Specials were not primarily concerned with earning the estimation of their peers, but looked forward to their work being prized by the ‘historian of the future’. William Simpson rightly considered artistic reportage to be a ground-breaking and peculiarly characteristic phenomenon of Queen Victoria’s reign that would be of immense value to future generations:

One result of this new phase of art is that the reign of no monarch has been illustrated before in a manner equal to that of her Majesty. All the events of her life, as well as those of her family, are on record in a pictorial form. Her Parliaments, councils, and wars have been minutely reproduced. All the public events of the time are on record by this new means.

(Notes and Recollections of My Life, hand-written memoirs, 1889, pp. 296-7).

For Simpson and his journalistic peers, the core value of graphic journalism lay in its ability to facilitate an affective, virtual experience of the news events they observed firsthand to readers of the metropolitan press then and now:

As a Special Artist I have at all times felt that I was not seeing for myself alone, but that others would see through my eyes, and that eyes yet unborn would, in the pages of the Illustrated London News, do the same. This feeling has at all times urged on my mind the necessity for accuracy; and I trust that those in the future, either the historian or the archaeologist, who may refer to the subjects I have contributed, will find no reason to doubt their faithfulness.

(‘The Special Artist’, Illustrated London News, 14 May 1892, p. 604)

As the artist prophesied, those researching his work in the current age are surprised at the latent vitality it still conveys and appreciate the ‘foresight’ with which he meticulously documented his drawings. Alexandra Jones, in a recent blog for the V&A, notes how in cataloguing Simpson’s Crimean sketchbook she felt ‘as if he could imagine someone like me examining his album over a hundred years later, and wanted to make sure I had all the information I might need’ (Alexandra Jones, ‘William Simpson’s Sketches from the Crimean War’, 5 May 2016: http://www.vam.ac.uk/blog/tag/william-simpson). Thanks to the advent of digital research tools, the ‘future historian’ is now slowly realizing the wealth of information on current affairs laid down in perpetuity by the graphic journalists of the Victorian age.

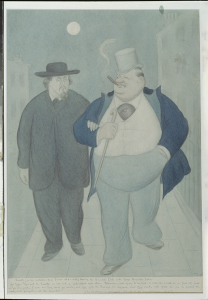

However, their value as works of art is yet to be re-assessed. Undoubtedly, this form of factual realism (based on the reportage of actual events rather than images inspired by them) propagated by ‘the Illustrated London News school, special-at-the-seat-of-war department’ (as described by the critic George Bernard Shaw in The World, 12 October 1887) had a circular influence on the broader developments in the fields of Victorian art and literature – a circumstance that needs to be appraised in greater depth. This caricature by Max Beerbohm from his series of illustrations of Rossetti and his circle (1916) attests to the friendship that existed between the special correspondent George Augustus Sala and one of the leading proponents of the Pre-Raphaelite movement, Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Similarly, comments by Harry Quilter, the Victorian art critic and writer, in which he identified the correspondence between journalism and the tenets of Pre-Raphaelitism, warrant further investigation. He ascribed the ‘keynote of the success’ enjoyed by ‘the new journal [the Graphic]’ to ‘the spirit in which the designs were conceived’ and argued that ‘this may perhaps be called the unconscious pre-Raphaelitism of all the contributors’. While the translation of scenes inspired by illustrated journalism into the realms of the Royal Academy has been explored (See Andrea Korda, Printing and Painting the News in Victorian London: The Graphic and Social Realism, 1869–1891, Ashgate, 2015), what remains to be discovered is the way in which the constant flow of topical representations of the Special Artists and their literary counterparts, the Special Correspondents, made in pursuit of their journalistic profession, altered the visual precepts of the Victorian public and their artistic expectations in the process of reshaping their everyday engagement with the world.

Of course, the well-known arguments about the flawed subjectivity of documentary photography and other empirical art forms are equally applicable to the ‘eyewitness’ material produced by the journalists. Furthermore, there is evidence that the Special Artists were not averse to using photography in the course of their reportorial duties. During a visit to Melton Prior, Henry Pearse recalled how,

Presently the sketch-books are laid aside and photographs produced which show how valuable an adjunct to a war artist’s kit the camera may be

(‘Famous War Sketchers, III’, 15 February 1893, The Sketch, p. 148).

Significantly, however, Pearse categorized the camera as ‘an adjunct’ tool in the artist’s documentary practice. The technological limitations of the medium in terms of the constraints upon image production (primarily long exposure times and the inability to easily reproduce photographs in the press) meant that, until the end of the nineteenth century, the camera could not cope with recording incident and spontaneity – the defining characteristics of a news event. Therefore, for the majority of Queen Victoria’s reign, the photographer would only play an ancillary, supporting role in the documentation of the news. Instead, the graphic journalists took the lead in communicating news data through the channels of the illustrated press with an exact, replicative ability now associated with filmed or photographic news footage.

In fact, the work of the Specials raised issues for the Victorians which still have current resonance for today’s audience, such as the desire for immediacy that drives our own 24-hour news culture; arguments about the use and influence of ‘embedded’ war correspondents and the complex skill of blending accurate fact with compelling detail to meet popular demand without erring into embellishment.

Signalling her own sense of continuity with her Victorian predecessors, in an address at St Bride’s Church, Fleet Street, on 12 November 2010, the late Marie Colvin, former Foreign Correspondent of the Sunday Times, explained the legacy left by William Howard Russell, ‘the first war correspondent of the modern era’:

Billy Russell, as the troops called him, created a firestorm of public indignation back home by revealing inadequate equipment, scandalous treatment of the wounded, especially when they were repatriated – does this sound familiar? – and an incompetent high command that led to the folly of the Charge of the Light Brigade. It was a breakthrough in war reporting. … Now we go to war with a satellite phone, laptop, video camera and a flak jacket. I point my satellite phone to South Southwest in Afghanistan, press a button and I have filed.

In an age of 24/7 rolling news, blogs and twitters, we are on constant call wherever we are. But war reporting is still essentially the same – someone has to go there and see what is happening. You can’t get that information without going to places where people are being shot at, and others are shooting at you. The real difficulty is having enough faith in humanity to believe that enough people be they government, military or the man on the street, will care when your file reaches the printed page, the website or the TV screen.