Opening of the Suez Canal

Apart from providing the allure of the exotic, the graphic journalists’ ability to virtually transport the reading public to overseas locations took on a more serious purpose in the context of making remote news events, such as the construction of the Suez Canal, more comprehensible. In his memoirs, William Simpson demonstrated how his work in this case, and that of the Special Correspondent William Howard Russell, had been instrumental in altering Britain’s official stance towards the building of the Suez Canal. Commissioned by the Illustrated London News to ‘illustrate the new route to India’, including a look at the Suez Canal then in development, Simpson set forth on 22 December 1868. In Cairo a letter of introduction brought him into contact with Ferdinand de Lesseps, the French developer of the canal project. Seizing the opportunity for a ‘public relations’ exercise, Lesseps invited a party of British delegates, including Simpson, Russell, and the ‘celebrated engineer’ John Fowler, to view the construction site because, as Simpson discerned:

M. Lesseps knew that Russell was to write letters to the Times, that John Fowler… would give practical opinions on the technical details, and that I would illustrate the whole.

The plan worked. Noting that until then ‘[i]t had been the traditional policy of British statesmen to oppose French influence in Egypt’ and that the prevailing wisdom had been that the ‘sand of the desert would fill up the Canal as fast as it was made’, dooming the enterprise to failure, Simpson recalled:

There was great surprise therefore when letters from Russell and Fowler, as well as my pictures, announced that the Canal was a success, that it was nearly completed, that the sand of the desert was a myth, and that the work when finished would be of the greatest advantage to Britain. From this explanation, it will be seen that, so far as Britain was concerned, our visit had almost a historical importance.

(The Autobiography of William Simpson, 1903, pp. 204-5)

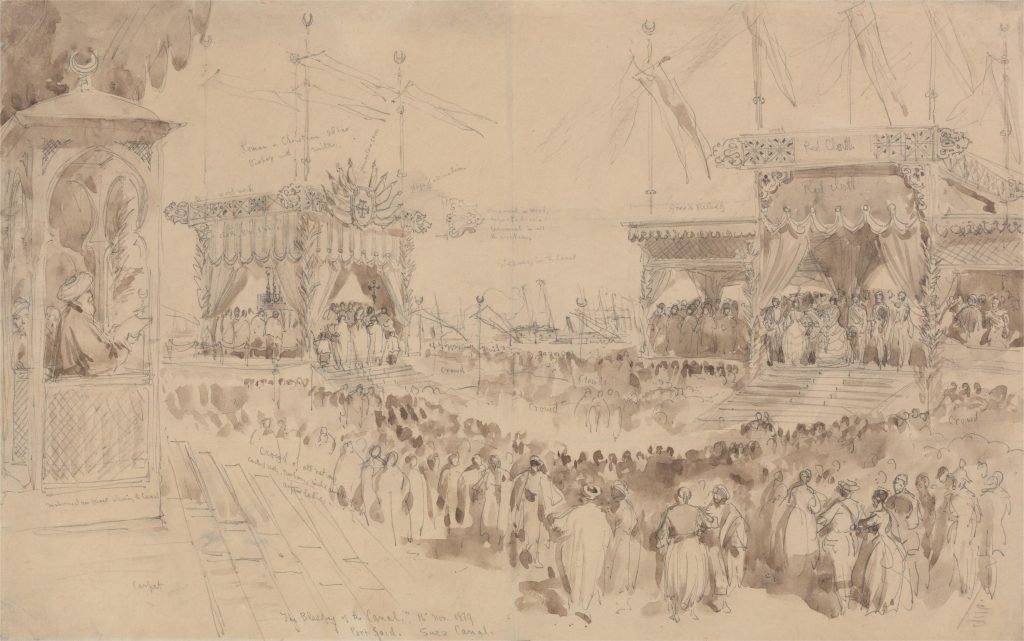

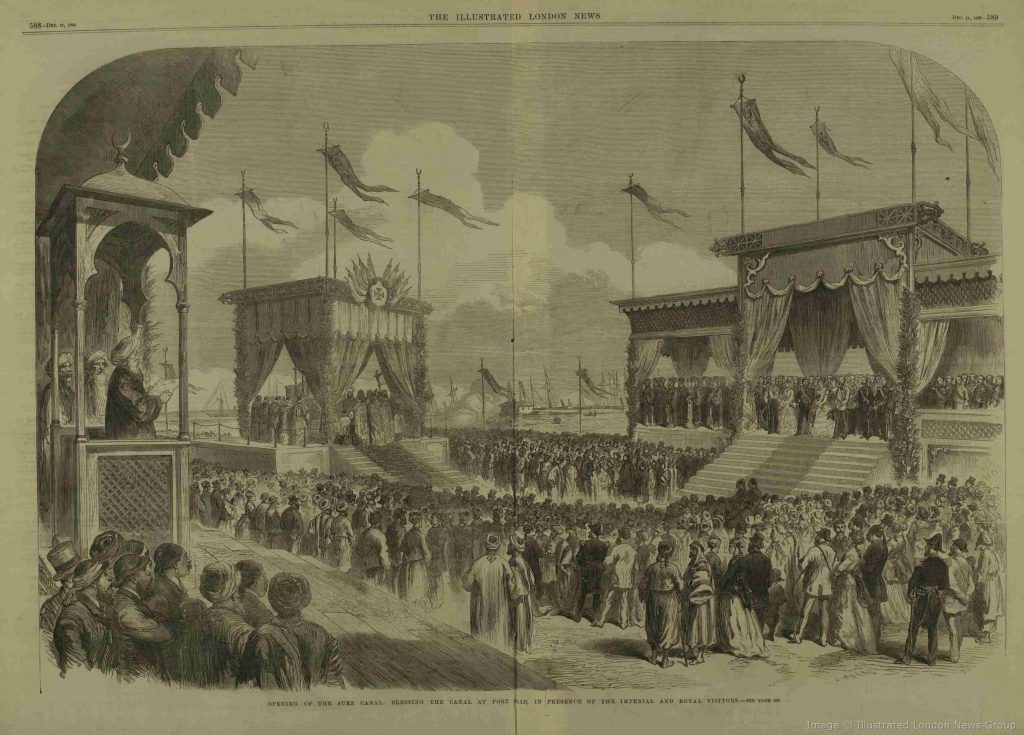

Categorised as ‘an illustrator’s sketch’, the particular form of imagery devised by the Special Artists to quickly describe and communicate the events they observed, this example of Simpson’s work derived from a subsequent commission from the paper to return and document the official opening of the Suez Canal on the 16 November 1869. For the first time ‘retained permanently on the staff of the Illustrated London News’ (from August 1869), and having received an invitation to the opening ceremonies ‘[o]wing to my personal acquaintance with M. Lesseps’, Simpson agreed a combined foreign assignment to report on the events in Egypt and a forthcoming great council of the Roman Catholic Church in Rome (Autobiography, p.224-5). Characteristic of his working methods, this sketch of the Blessing of the Suez Canal that took place at Port Said on 16 November 1869, made with pencil and sepia wash, demonstrates how Simpson annotated his view of the event with details of this ‘Pan-religious function’ which had ‘Latin, Greek, and Mohammedan priests officiating’ and ‘imperial and royal personages’, such as Lesseps’s second cousin, the Empress Eugenie, who formally inaugurated the canal, attending. His working conditions were chaotic:

We started through the Canal on the 17th, and as it was necessary to catch the weekly mail from Egypt, I remember I had to sit on a pile of luggage getting my sketches ready to post at Ismailia. When we arrived there on the 18th, Shepherd, who represented a Bombay paper, and I went ashore to post letters, and when we came back our ship was gone

(Autobiography, p. 227).

For reasons of expediency, Simpson outlined the key features of the event (including the ornamental structures and main protagonists) and relied on notes such as ‘Crowd of all nations, cocked hats, turbans’ to provide direction to the staff draughtsman appointed to engrave the image for publication on its arrival in London. On receipt, the draughtsman extrapolated details from these instructions to complete the work. While still at base representative of the actual event, the final illustration that appeared in the press about three weeks later thus combined elements of fact and imagination – as a comparison of the two stages of the image confirms.