Crimean War, 1854-56

Although the employment of foreign correspondents for major metropolitan dailies like the Times dates from the early nineteenth century, the peculiar role of the Special Correspondent and Special Artist as roving journalists sent out to report upon particular events was forged in the 1850s with the famous Crimean War reports of William Howard Russell for the Times, and the sketches of William Simpson (aka ‘Crimean Simpson’) for Colnaghi’s, the London print publishers. Russell’s reports were gripping, eye-witness accounts that brought the war home to British readers. In exposing the privations of the army and negligence of the War Office, they contributed to the downfall of the Aberdeen government. Similarly, alongside his superbly detailed battle scenes, Simpson’s sketches of the fever-racked victims at Balaclava stirred the nation’s conscience. Thereafter, as newspaper competition grew, both the reports from ‘Our Special Correspondent’ and the sketches furnished by ‘Our Special Artist’ in the illustrated press became increasingly important selling points. Newspaper readers would never again be content with less than first-hand accounts from the seat of the war.

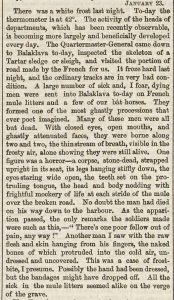

Russell’s unflinching graphic description of the sufferings of the British troops is vividly demonstrated in the excerpt from his report on ‘The Siege of Sebastopol’ published in the Times on 12 February 1855.

Such hardship is also captured in Simpson’s rapidly executed watercolour, ‘Huts and Warm Clothing for the Army’, where British troops, numb with cold, trudge through the muddy snow past half-built barracks.

In his memoirs, handwritten in 1889, Simpson recalled meeting Russell ‘in the mud of Balaklava’ shortly after arriving at the battlefield. While celebrating the fact that he and Russell were ‘the two oldest “Specials”’ then living, he also teasingly reflected on the difference in their commitment to the more perilous aspects of their jobs:

I thought nothing myself at the time of this going into the trenches, but when I read Russell’s letters to the Times, which were afterwards published, I noticed that he never ventured down except when there chanced to be an armistice.

(Notes and Recollections of My Life, p. 44)

This wry observation was diplomatically removed from the edited version of his published autobiography, but the latter did retain a passage in which Simpson compared the pitfalls and advantages of their respective roles. Acknowledging a qualitative difference in their treatment on the Crimean battlefield, Simpson attributed this distinction to the compelling power of the literary form over the artistic:

I found then, as I have since, that the ‘Special Correspondent’ of a daily paper is a far more important personage than a ‘Special Artist.’ Words are far more direct and specific than a picture. The correspondent appeals to a larger number of persons, and what he says may have also a political bearing, which brings him more prominently before the public than the artist.

However, the upside of this circumstance, was that, ‘at the seat of war’ the artist tended to be ‘in a more pleasant position’ because it meant he generally escaped official censure and was ‘welcomed wherever I went’, while, on the other hand:

If the correspondent blames any one, or any body of men, in the performance of duty, he is hated. If he praises any one there are always others who consider they have done equally well with the ones complimented, and they abuse the correspondent for not noticing their merits. Of course those who are praised are very friendly to the correspondent. The result is that the correspondent is much courted and much hated. I escaped all this.

(The Autobiography of William Simpson, R.I., 1903, p. 36)