Franco-Prussian War, 1870-71

The conflict that broke out between France and Prussia in the summer of 1870 represented a watershed in the development of the war correspondence of the Specials. It was the first major conflict to be reported via extensive use of the telegraph. Archibald Forbes repeatedly scooped his rivals and transformed the fortunes of the Daily News in the process, trebling its circulation, by making extensive use of the telegraph to relay his descriptive letters from the front. As Philip Knightley explains, ‘It was the Franco-Prussian War that marked the decline of William Howard Russell and the rise of Archibald Forbes, the leader of the new guard’ (The First Casualty, 2000, p. 47). Notwithstanding the increasing use of the telegraphic despatch, however, the public craving for descriptive letters from ‘Our Special Correspondent’ at the seat of the war, established earlier by Russell, remained strong. As an editorial in the Times argued,

The bare facts communicated by the telegraph are tantalizing. It is the ‘special correspondent’s’ duty to make history out of that fleshless skeleton, and, when the electric spark fails, his graphic pen supplies the form and hue of life.

(Times, 21 July 1870, p. 9)

Special Correspondence sought to transport readers imaginatively to the seat of the war, as the account given by the special correspondent of the Daily News (probably Hilary Skinner) of the field of battle the day after the surrender of the French at Sedan in September 1870 illustrates.

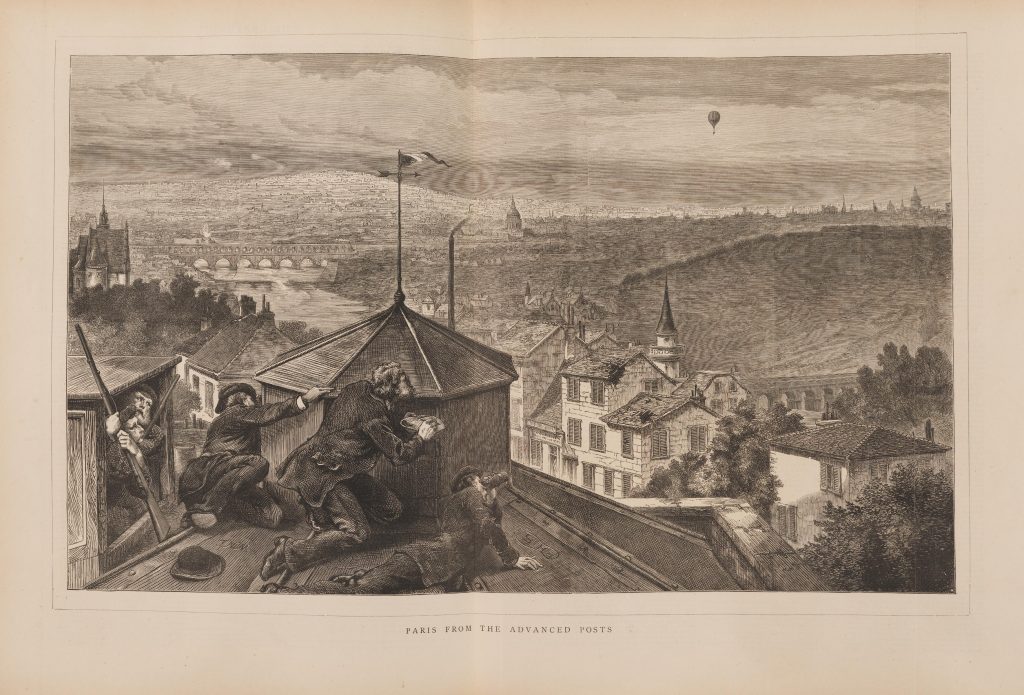

Following the efforts of their Special Artist, Sydney Prior Hall, the Graphic was quick to claim that ‘[t]he artist has manifested himself as necessary now to the due reporting of important occurrences as the special correspondent’ and to chart how this ability ‘week by week to set before the public a pictorial chronicle of the war even to its minor incidents’ had altered the traditional conventions of war art, which was no longer ‘tinctured by the old fashioned classicality’ (‘War and the Fine Arts’, 18 February 1871, p. 143). The key to the popular enthusiasm for their coverage was Hall’s aptitude for providing a vicarious experience of the events he witnessed. ‘Imagination and individuality’ were seen to be the ‘distinguishing features of his work’ (Barnett, ‘The Special Artist’, p.168) and he became known for supplying spontaneous, evocative images that suggested the lived experience of the war from the perspective of the individuals involved. Highly articulate, he often supplied an accompanying written explanation of the inspiration for the image. This double-page engraving, with its exhilarating perspective, resulted from ‘a journey in company with two English officers to the extreme front, to obtain a nearer view of Paris’ while staying at the Chateau Meudon (‘Paris from the outposts’, Graphic, 5 November 1870, p.446). Incorporating an impression of the reconnaissance party precariously positioned on a rooftop, he managed to suggest their nervous tension at the time:

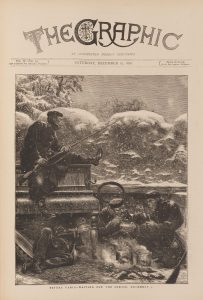

Hall deliberately offset images of the more ‘ghastly’ aspects of the war with affective glimpses of the soldiers occupied in more mundane activities, to emphasise the pathos of the situation and engage the public’s sympathy. In ‘Before Paris – Waiting for the Sortie, December 3, 1870’, he provided an incongruous view of a group of soldiers he’d spotted making supper on a chilly evening within the grand remains of a derelict property.

Hall deliberately offset images of the more ‘ghastly’ aspects of the war with affective glimpses of the soldiers occupied in more mundane activities, to emphasise the pathos of the situation and engage the public’s sympathy. In ‘Before Paris – Waiting for the Sortie, December 3, 1870’, he provided an incongruous view of a group of soldiers he’d spotted making supper on a chilly evening within the grand remains of a derelict property.

While quartered together in Magency, Archibald Forbes provided the necessary ‘effective and telling’ title for The Buried Quick and the Unburied Dead, Hall’s representation of one of the most gruesome scenes they had both witnessed of alert Prussian sentries surrounded by the bodies of their dead comrades. Recalling the circumstances behind the conception of these sketches, Forbes opined:

It seems to me that no one who saw them as they appeared in the Graphic of the period but must have felt and been thrilled by the quiet, true power and the touchingness of the sentiment which they disclose

(‘Mr Sydney P. Hall of the “Graphic”’, The Sketch, 1 February 1893, pp. 27 & 30).