Introduction

Surveying English Journalism and the Men Who Have Made It in 1882, Charles Pebody described George Augustus Sala as

a newspaper contributor without a rival in his own special line. Dr Russell and Mr Archibald Forbes may sketch a field of battle in a way that Mr Sala could not touch; but fields of battle do not, happily, often call for the descriptive powers of a Russell or Forbes; and except upon a field of battle, Mr Sala is practically a man without rival. His readiness, his picturesque sensibility, his aptitude for vivid and graphic writing, his great powers of expression, and his still greater powers of illustration, constitute him the beau-ideal of a journalist.

(p. 142)

Sala’s capacity to transport his readers through the graphic techniques of his Special Correspondence was apparent from the beginning of his career, as his description of the Gostinnoi-Dvor or great bazaar of St Petersburg for Household Words as part of his series, ‘A Journey Due North’, demonstrates. This flamboyant account is typical of Sala’s ‘word-painting’, its appeal lying in the wit and ingenuity with which its far-fetched ingredients are gathered to form the miscellaneous compendium. While opposition between the familiar and the foreign was a characteristic trope of earlier travel writing, Sala’s description estranges the known points of reference invoked through their fantastical assemblage.

![Extract from [George Augustus Sala,] ‘A Journey Due North’, Household Words, 22 November 1856, p. 447.](https://research.kent.ac.uk/victorianspecials/wp-content/uploads/sites/2017/2017/01/7.1-GAS-description-of-Gostinnoi-Dvor-HW-172x300.jpg) Aware of the tradition of ‘armchair travel’ in which he participated, Sala reminded the readers of the Illustrated London News, in preparation for the upcoming coverage of the Prince of Wales’s Indian Tour of 1875-6, that virtual travel could be of greater benefit than an actual journey:

Aware of the tradition of ‘armchair travel’ in which he participated, Sala reminded the readers of the Illustrated London News, in preparation for the upcoming coverage of the Prince of Wales’s Indian Tour of 1875-6, that virtual travel could be of greater benefit than an actual journey:

We may learn a great deal from an artificial moving panorama when we are seated in a comfortable arm-chair and the panorama glides gently before us. On the other hand, we are apt to derive but very little instruction from a natural panorama, which is stationary, while we dash past it in express-trains or rapid steam-ships. To find those who may in the greatest measure profit by the Royal trip to Hindostan I venture to look at home. The graphic and animated description of the Prince’s tour… – should awaken in the minds of the public at large a lively and a lasting interest in India and all appertaining to it.

(‘India and the Prince of Wales’, 16 October 1875, Special Issue, p.7)

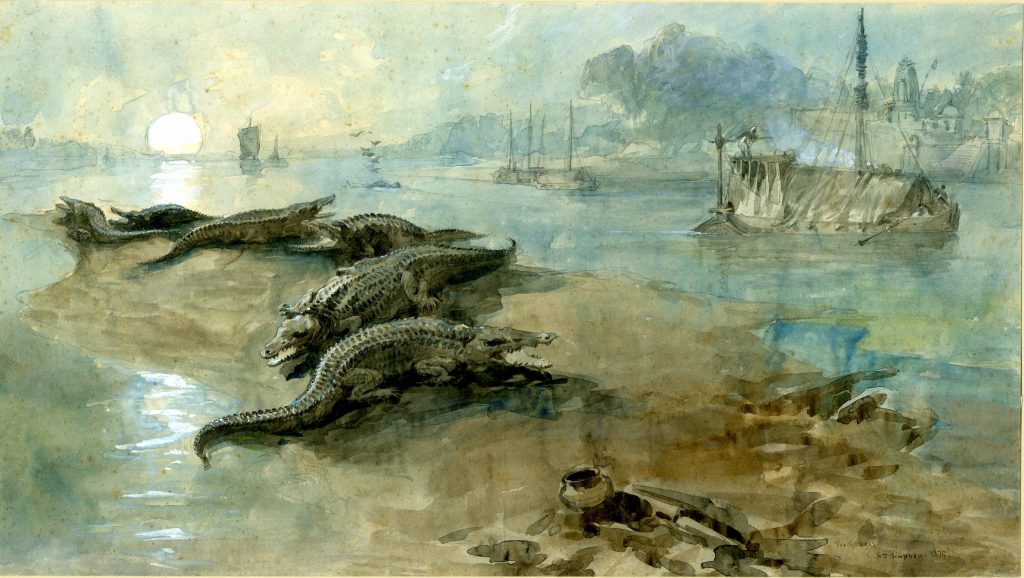

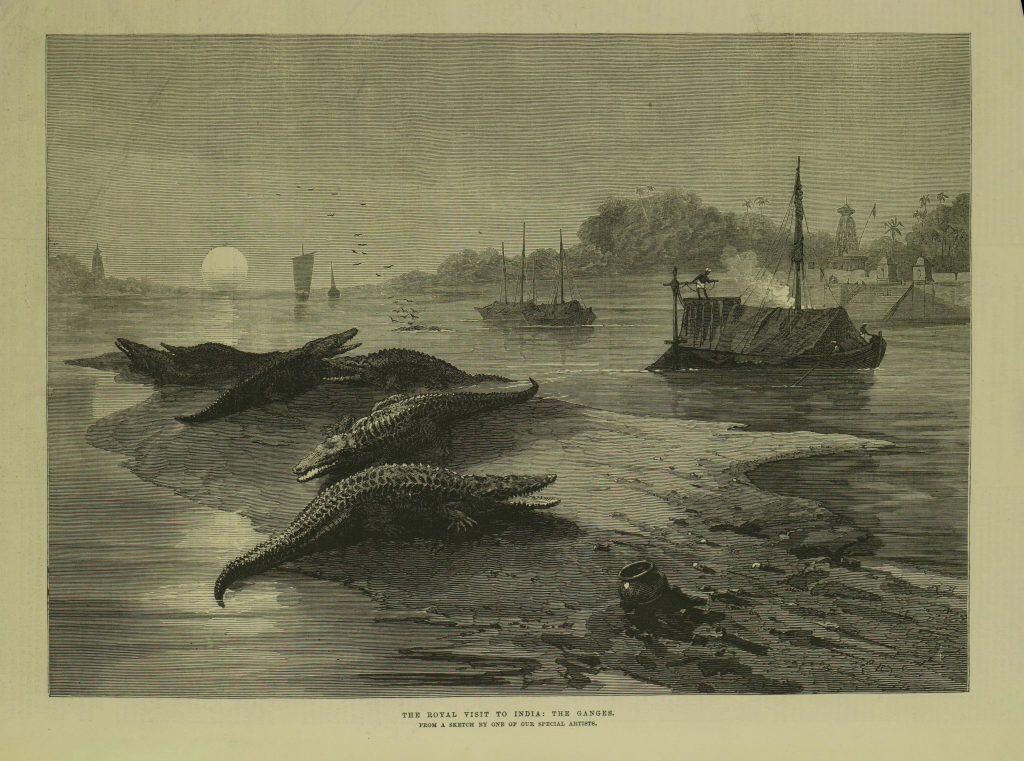

Tapping into this appeal to the exotic in transporting newspaper readers to unfamiliar locations, the Illustrated London News published William Simpson’s picturesque view of crocodiles on the banks of the Ganges as part of their representation of the Prince’s visit. Conscious of the compelling quality of the image, the artist worked it up into a finished watercolour (now preserved in the British Museum), and subsequently exhibited it in India ‘Special’, the exhibition he held independently on his return to celebrate his work as a Special Artist on the tour. This follow-up display gave visitors the chance to engage with his illustrations again, but this time in colour – adding a new dimension to the imaginative exercise.