Heroic Adventurers

The inherent pluck that gained the Special Correspondents and Artists their heroic reputations is vividly captured in Frederic Villiers’s description of Archibald Forbes: ‘Amidst the noise and din of battle, and in close proximity to bursting shells, whose dust would sometimes fall on the paper, I have seen him calmly writing his description of the battle, not taking notes to be worked up afterwards, but actually writing the vivid account that was to be transmitted to the wire, and the work was always good.’ (Peaceful Personalities and Warriors Bold, London 1907, p. 243.)

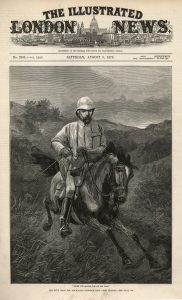

‘The Zulu War: Mr Archibald Forbes’s ride from Ulundi’, Illustrated London News, 9th August 1879

© IllustratedLondonNewsLtd / MaryEvans

Given the arduous demands of the role and the adventures to which it led, the Special sometimes became more newsworthy than the news he was delivering. Archibald Forbes’s legendary ride from the field of British victory at Ulundi to dispatch his report as Special Correspondent for the Daily News is a case in point. When the battle of Ulundi brought the war to an end on 4 July, Forbes rode alone through hostile territory to reach the nearest telegraph office at Landmann’s Drift, some 110 miles distant, and sent first news of the British victory. The heroic quality of the ride was lauded in the Illustrated London News with a front-page engraving – based on notes made by Melton Prior, who was also present in Ulundi, and worked up by Richard Caton Woodville, Jr. – of ‘the bold, unwearied, dauntless, solitary horseman, “bloody with spurring, fiery red with haste”’ (9 August 1879). Woodville was a military artist, underlining the extent to which Forbes’s prowess as Special Correspondent was being merged with the heroism of the British army by the metropolitan press.

Ironically, Forbes himself would comment on Villiers’s own disregard for personal safety. Noting that he had first made the acquaintance of Villiers during the Turkish-Serbian War of 1876, he described how he saw Dochtouroff, one of the Russian Generals, reprimanding Villiers ‘vehemently on account of his recklessness, as that young man sat on a hillock among the dropping shells while he calmly sketched the hard-fought struggle’ before confirming the justness of the rebuke:

Among Villiers’ faults is – or was, for he may have reformed since he and I campaigned together – a regardlessness of personal danger; to which accusation, however, he would, no doubt, plead the truism that it is among the obvious duties of the war artist to take his life in his hand.

(Forbes, The Sketch, 26 April 1893, p. 773)

Underscoring the chilling truth to this assertion, and consequentially, the justness of their celebrated status, Forbes concluded his account of Villiers’s career with a sombre reminder of his proximity to several Special Correspondents when they died in the course of their duties:

He was near Herbert Stewart when the Arab bullet cut short a career of brilliant promise: he witnessed the death of his comrade Cameron, the able and daring correspondent of the Standard, and he was walking with St. Leger Herbert of the Morning Post when the latter was killed.

(p. 775)