Maiden Voyage of the Great Eastern

Like the railroad, steamship, photograph or telegraph, with all of which it was closely associated, the journalism of the Special Correspondents and Artists brought the world closer, shrinking space and time and conveying readers to distant places. Indeed, they were reporting upon the very developments in transport and communications technology upon which the delivery of their own graphic news coverage depended.

Extract, From Our Special Correspondent, ‘The Trial Trip of the Great Eastern’, Daily Telegraph, 12 September 1859, p.5.

© The British Library Board. NRM MLD7

On 9 September 1859, Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s massive 22,500-ton steamship left the Thames estuary for Weymouth on its maiden voyage. As the largest ship the world had ever seen, she was accompanied by a sizeable press contingent that included George Augustus Sala, Special Correspondent for the Daily Telegraph. The voyage was tragically cut short by a boiler explosion just after she had passed Hastings. In the excerpt from his report of the accident reproduced here, the eye-witness veracity of Sala’s account is emphasised as he recounts the event from the perspective of his actual position in the dining room.

According to his biographer, Ralph Straus, it was Sala’s despatches on this trial voyage of the Great Eastern that confirmed the proprietors of the Daily Telegraph ‘in their belief that they had found a prince of special correspondents’ (Sala: Portrait of an Eminent Victorian, 1942, p. 151).

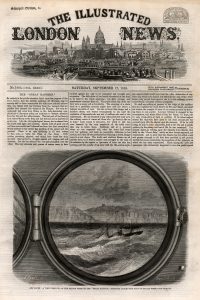

Cover of the Illustrated London News, 17th September 1859, featuring a report on the Great Eastern ship and engraving based on a sketch of a view off Dover from one of the saloon ports.

© IllustratedLondonNewsLtd/MaryEvans

In contrast to Sala’s graphic narrative of tragedy, and presumably not wanting to waste a unique piece of documentary art already furnished by their Special, the Illustrated London News chose to accompany their account of the accident with a sketch of the view from one of the saloon portholes during the gale the previous week. The peculiar device of framing the view ‘off Dover’ as seen through the porthole is both an authenticating strategy designed to assure the reader of the Illustrated London News that this sketch was taken ‘on the spot’, and a way of seeing that situates the viewer in the position of the artist, sharing the immediacy of his perspective on the scene.