Prince of Wales’s Royal Tour of India, 1875-76

War correspondence was not the only source of William Howard Russell’s fame. As a member of the Prince of Wales’s circle, he managed to secure privileged access in reporting royalty, a position that drew criticism from other sections of the press for such preferential treatment. His invitation to accompany the Prince as ‘Assistant Private Secretary’ on his tour of India in 1875-76 is a case in point. While the press debated various issues associated with the tour in the months leading up to it, of greatest interest to every newspaper was how it should be represented. When it became known that Russell would be the only journalist allowed to accompany the Prince on the Serapis from Brindisi to Bombay, and that the other Special Correspondents would ‘go with the baggage in the Deccan’ (‘English Affairs’, New York Times, 8 October 1875, p. 1), a furious remonstrance arose from the rest of the press. Harry Furniss believed that the royal preferment for Russell came down to personality:

Russell owed much of his popularity and patronage to his Irish humour. He was always good company, and his ceaseless flow of stories, retailed in dulcet tones of a rich Irish brogue, were greatly relished by King Edward, who, as Prince of Wales, made Russell one of his staff companions on his tour in India.

(‘War Correspondents and some “Specials”’, My Bohemian Days, 1919, p. 124)

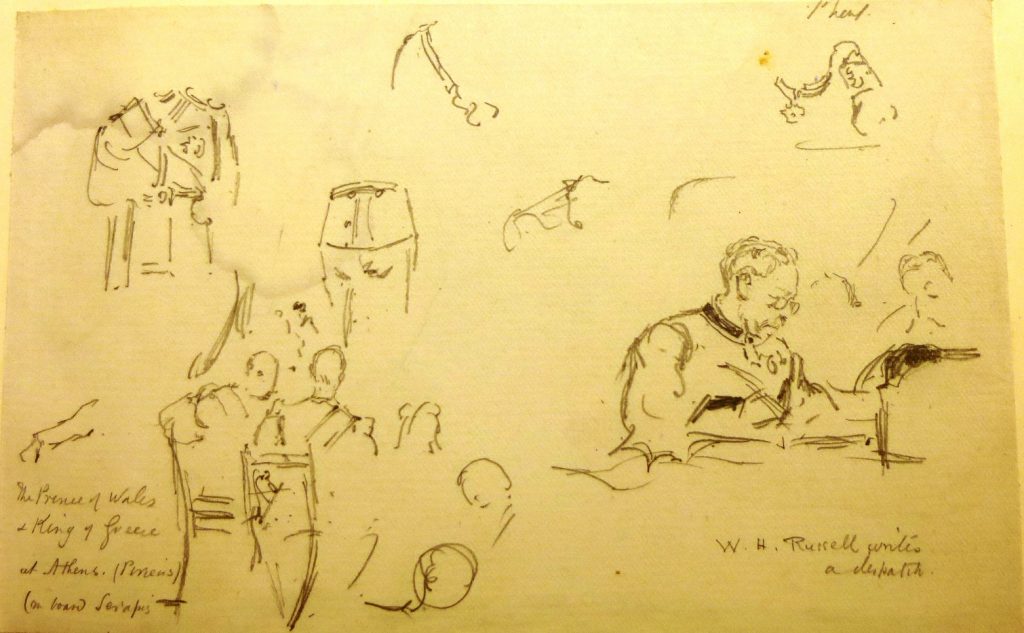

This page from Sydney Prior Hall’s sketchbook, similarly favoured as the official royal artist, shows his quick pencil study of Russell writing a dispatch on board the Serapis seen alongside a drawing of the Prince of Wales and King of Greece seated at table. The juxtaposition of the figures demonstrates the assimilation of both Specials into the intimate circle of the Royal entourage.

Ironically, however, Russell found his privileged position as part of the Royal suite served to constrain rather than facilitate what he could report. Moreover, the difficulties associated with his ambiguous position as simultaneously Special Correspondent for the Times and Assistant Secretary of the Prince, were compounded by his inability to adapt to changing technologies. By the mid 1870s, following Forbes’s success in scooping his rival correspondents in reporting the Franco-Prussian war, increasing use was being made of the telegraph even though the costs of wiring remained high. But Russell disliked the medium and employed a system of combined reporting of the Prince’s tour by both telegraph and special mail dispatch. He wrestled with the different time-lags involved in publication in each case and continued to complain from India to the Times’s editor, John Delane, ‘I cannot explain to you the paralysing effects of sitting down to write a letter after you have sent off the bones of it by lightning’ (Letter to John Delane, 24 March 1876, Times Newspapers Ltd. Archive.)

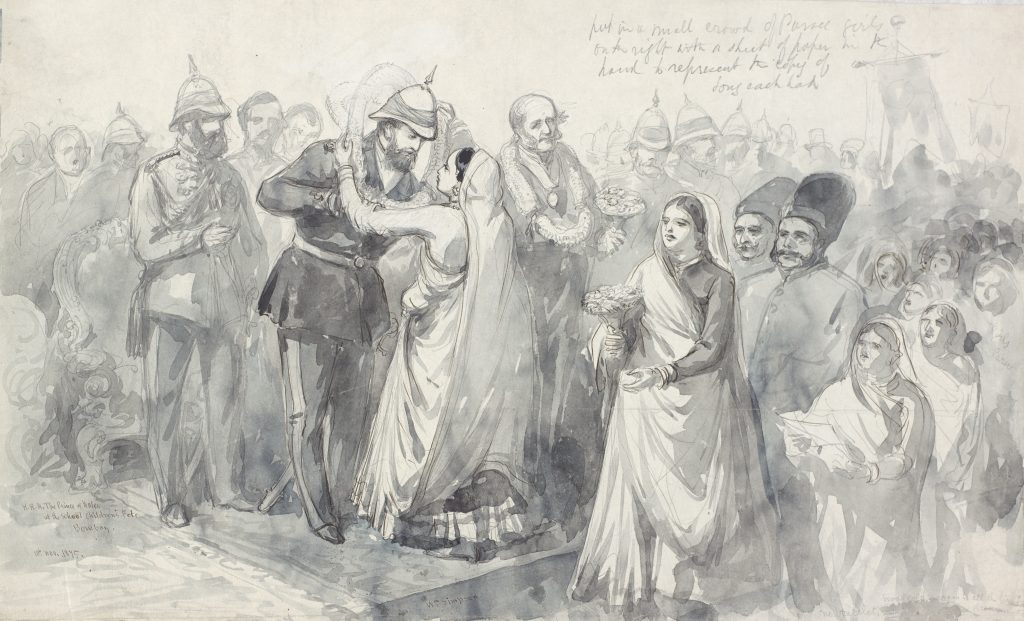

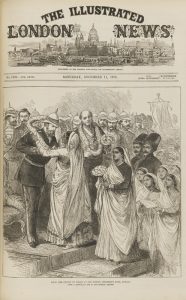

On this occasion, William Simpson, often himself the recipient of private royal commissions, travelled separately for the Illustrated London News, along with two artist-reporters for the Graphic (Walter Charles Horsley and Herbert Johnson). Over the course of this seminal royal tour, which lasted seven months in total (including the journey to and from India), between them they channelled a constant stream of images back to Britain through the pages of the periodical press. They chronicled every aspect of the Royal visit to an unprecedented degree, including civic ceremonies such as this representation of the Prince of Wales’s visit to the School Children’s Fete on 10 November 1875 in Bombay. Documenting an event designed to promote the educational benefits instituted by the British administration, Simpson, in this illustrator’s sketch, provided an attractive view of the moment the Prince received a garland of jasmine from ‘A beautiful Parsee girl, attired in pink satin, whose name is Miss Dhunbaee Ardaseer Wadia’ (ILN, 11 December 1875, p. 586).

The sketch became a front-page image for the Illustrated London News. In engraving the work, the staff draughtsman sharpened the details but closely adhered to Simpson’s original composition and instruction to ‘Put in a small crowd of Parsee girls on the right’ each with a song sheet in hand. The accompanying written description in a subsequent column of text gave an added layer of aural information that – in tandem with the image – gave readers the prompts they needed to animate the illustrated moment in their minds:

The sketch became a front-page image for the Illustrated London News. In engraving the work, the staff draughtsman sharpened the details but closely adhered to Simpson’s original composition and instruction to ‘Put in a small crowd of Parsee girls on the right’ each with a song sheet in hand. The accompanying written description in a subsequent column of text gave an added layer of aural information that – in tandem with the image – gave readers the prompts they needed to animate the illustrated moment in their minds:

A band of Hindoo girls then sung an anthem, in the Mahratta language, followed by Parsee girls, with the same in the language of Guzerart, expressing their joy at the Prince’s arrival and their fervent wishes for his happiness

(ILN, 11 December 1875, p. 586).

When Simpson later exhibited his drawings from the tour in an exhibition titled India “Special”, this ability of the works to convey a virtual experience of the Prince’s tour was remarked upon, with one reviewer commenting:

Looking over these numerous and able sketches, … one cannot but reflect on the immense value of such attendance upon a semi-royal progress of this kind. But for the efforts of these gentlemen, wielding the pen of the ready writer and the pencil of the ready draughtsman, the tour which has been followed with such interest by millions of people would have been a mere matter of hearsay, of no interest at all, except in any ultimate results, to those at home. As it is, between the pen and the pencil we almost follow the whole thing, and feel as if we had been there

(The Builder, 10 June 1876).