Marquis of Lorne’s Tour of the North West Province in Canada 1881Royal Pageantry and Patronage

There was no distinction between the royal entourage and the press cohort when it came to reporting on the Marquis of Lorne’s (Queen Victoria’s son-in-law, husband of Princess Louise) tour of the North West provinces of Canada in 1881. Charles Austin was the Special Correspondent for The Times, while the Graphic was quick to report that as ‘Mr. Sydney P. Hall, has been invited to accompany the Governor-General, we hope to publish from time to time the chief incidents of interest of the trip’. Hall had also provided coverage of the young couple’s first royal tour of Canada in 1879, shortly after Lorne had been appointed to the governorship in 1878. For this subsequent tour, the official party was a relatively small group and Hall and Austin travelled as intimate insiders – allowing them to relay a correspondingly close, personal view of Lorne’s journey to the reading public. One desired outcome from this collaboration between the press and the royal family was that it would help present the region as a destination ripe for emigration. The Graphic framed their opening remarks accordingly:

Although Lord Lorne will really only travel through a comparatively small section of the British North American Empire, the district which he has chosen is of considerable importance, for where but a short time since only hunters and trappers existed, the vanguard of agriculturists is now steadily advancing, while the old forts of the Hudson’s Bay Company are being transformed into townships and agricultural centres. … The great and undeveloped resources which the Canadian Dominion presents for emigrants, however, are being gradually recognised, and one good effect of Lord Lorne’s tour will undoubtedly be to bring prominently into notice a region which possesses a cold climate in winters, it is true, but which, at the same time, offers great advantages to the enterprising and the industrious.

(‘To the Great North-West with the Marquis of Lorne’, Graphic, 31 August 1881, p. 164)

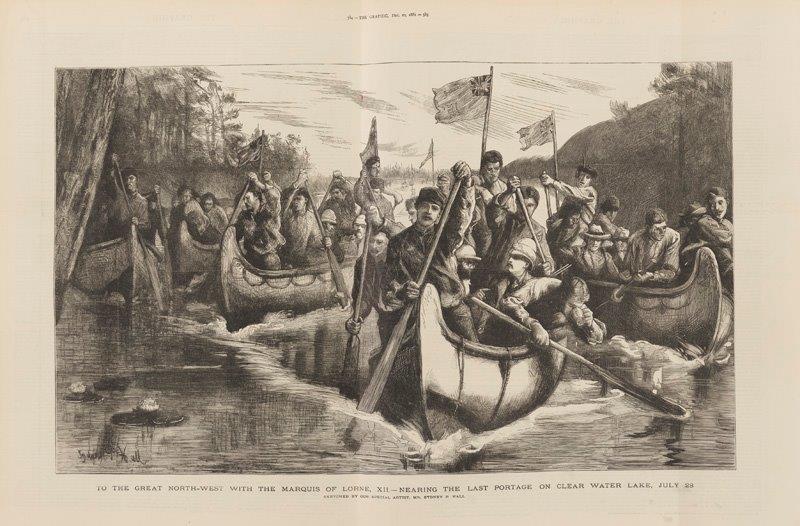

The Graphic enlivened their coverage with extracts from the artist’s diary, which conveyed Hall’s direct impressions of the events, incidents and encounters he observed in the course of his travels. Hall made comic mileage out of the physical discomforts endured by the party, with illustrations such as the one of ‘The Times’ [Austin] ‘in his Wigwam on the Prairie’ working under a mosquito tent to avoid being bitten (Graphic, 1 October 1881, p. 339). He sought to relay the sensations the participants experienced, with, for instance, images that suggested the sublime effect upon members of the party faced with the vast expanse of the prairie (Graphic, 4 February 1882, p. 99). Presented as a double-page image, in this representation of Nearing the Last Portage on Clear Water Lake, showing the forward movement as if head on, Hall endeavoured to replicate for the readers a visceral sense of the thrill and exhilaration he had felt as the party raced towards the last portage (the reach of land between two lakes) in ‘brilliantly painted bark canoes’ (Graphic, 10 December 1881, p. 579).

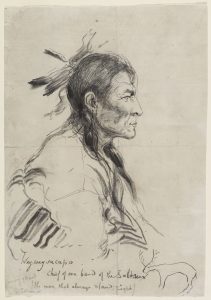

As was his custom, Hall captured portrait vignettes of the most interesting individuals he came across, including this compelling study (now held with 250 other original examples of the artist’s work in the Public Archives of Canada) of ‘Waywaysacapo, a Saulteaux chief at the pow-wow at Fort Ellice, and his mark, August 13, 1881.’ One method Hall used to help his audience engage with these sights of – what seemed to Victorian eyes – a strange, exotic people – was to identify points of familiarity:

The profile of the Indian chief, Waywaysacapo, struck us all by his likeness to Gladstone. The interpretation of his name (the man who always stands or, as some said, is right) seemed at least to the liberals of the party, peculiarly appropriate. The interpreter told him how like he was to the greatest of the Chiefs of England. He did not, however, seem to appreciate the honour.

(Graphic, 1 October 1881, p. 342)

As was the case to varying degrees with all the Specials, the artist-reporter echoed the imperial prejudices of his times – and, as the above extract demonstrates – the vicarious vision he offered was that of an outsider looking in.

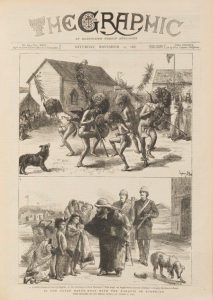

Hall projected back to Britain powerful but encoded images of a remote terrain under British dominion, which were both anthropological and imperialist in character. In this front-page image, the Graphic combined his dramatic view of a First Nations ceremony enacted for Lord Lorne – a buffalo dance, involving four men and a boy wearing buffalo head masks, that had taken place at Fort Qu’Appelle on 18th August – with that of an incident in the street that emblematised Dr MacGregor’s (the ‘famous preacher’ travelling with Lorne) missionary zeal. The former focused on the ‘diabolical effect’ of the spectacle, created by the masks of ‘matted hair’ and horns that ‘made them live like very devils’, with Hall demonstrating how the dancers, as if taking on the animus of the animal, had ‘seemed to imitate the movements of buffaloes pawing the ground, jerking their heads from right to left; tossing them, and grunting with spasmodic ugh-e-ugh.’ With telling juxtaposition, the second showed the Doctor stopping to bless ‘pagan’ children he happened to meet after attending a service at the Mission House (Graphic, 19 November 1881, p. 507).

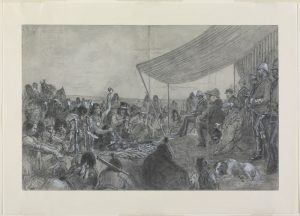

The keynote image of the entire tour was undoubtedly Hall’s representation of ‘the Pow-Wow at Black Feet Crossing, September 10’. Reproduced in the Graphic as a double-page spread on 5 November 1881, in his sketch, seen here, the artist-reporter highlighted the sight of ‘Chief Crowfoot, Chief of the whole Blackfeet nation’, seated on the Union Jack, making entreaties to Lord Lorne. Described as ‘the most picturesque and interesting of all such gatherings’ (which involved 2,100 Blackfeet and 450 Surcees) the scene marks the poignant moment when, surrounded by his warriors, Crowfoot, who ‘was in mourning, and for sackcloth and ashes wore a buffalo robe and no moccasins’ illustrated the plight of his tribe by holding up a ‘tin cup to show how much flour was doled out to each of his people – poor flour too, and he compared himself and his tribe to that empty pannikin, for so they had been since the buffalo had left them’ (Graphic, 5 November 1881, p. 459). The artist later worked up his sketches into two more elegiac compositions – first in pastel and then a large-scale oil (now in the collection of the Gilcrease Museum, Oklahoma) – in which he transformed Crowfoot into a brave standing figure, with arm proudly raised, declaiming against the fate of his people. The potency of these later works relies on the indexical link they retained to the actual event, yet their elision of factual and fictive elements brings to the fore how the work of the Special Artist essentially oscillated in status between art and journalism.