The Parnell Commission (1888-89)

Cause Célèbres, such as the Parnell Commission, called for the services of particular Specials to be dedicated to reporting on the entirety of the proceedings for a protracted period. Sydney Prior Hall was considered to have excelled himself in the comprehensive coverage he provided for the Graphic on this judicial inquiry, which took place at the Royal Courts of Justice over the course of 14 months starting in September 1888. In his biographical profile of Hall, Lewis Lusk recalled how:

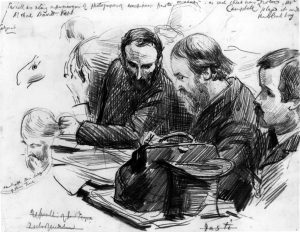

On each occasion [the Parnell Commission and the Jameson Raid Enquiry] he was in court the whole time, busy with a swift revealing pencil which missed no turn of affairs. The fighting figure of Parnell fascinated him, and he brought out the Irish leader’s personality very remarkably.

(‘A Famous Journalist’, Lewis Lusk, Art Journal, 1905, p. 279)

The special commission was set up to investigate the allegation that the leader of the Irish nationalists and a chief proponent of Home Rule, Charles Stewart Parnell MP, had explicitly condoned the murders of two members of the British Government in Ireland in Phoenix Park, Dublin in 1882. Journalism itself was on trial, as the case centred on a facsimile of a letter published by the Times in 1887, seemingly signed by Parnell, in which he appeared to approve the assassinations. Sensationally, following his cross-examination, the Irish Journalist Richard Pigott privately confessed to the Special Correspondents Henry Labouchere and George Augustus Sala that he had forged the damning letter before fleeing and taking his own life in March 1889 – leaving them to testify to his calumny in court.

Seeking to provide an exact chronological record, Hall produced a multitude of distinct images, interspersing single portraits of particular participants with scene-setting views of the courtroom and anecdotal records of the main incidents as they took place. Indicative of the pioneering serial art form the artist-reporters devised in response to the exigencies of documenting multi-faceted, long-drawn-out news events (in this case involving the testimony of 450 witnesses), taken together as a body of work these illustrations show how they function cumulatively in a synecdochic fashion, with the abstracted, partial representations being used, when arranged collectively, to suggest the actuality of the whole occurrence. Hall’s drawings were reduced in scale to fit the page and published in groups alongside a verbatim transcript of the relevant court proceedings. Notably, the original pencil studies (now jointly preserved in the National Portrait Gallery, London and the National Gallery of Ireland) have a spontaneous, vital quality that has been somewhat diminished in the translation to the hardened line of the engraved form – revealing an acknowledged downside to the reproductive technique often grumbled about by the Special Artists. Nonetheless, akin to a film still, a technological development for which these documentary graphic sequences are arguably a direct precursor, works such as this drawing of Parnell, shown seated with his lawyers, intently concentrating as he annotated photographs of newspapers that would be used in evidence, once published, allowed the Graphic’s readers a vicarious glimpse of that day’s action in court – with the interplay between the written and visual accounts, which are mutually contextual, again being key to the animated effect of both documentary mediums.

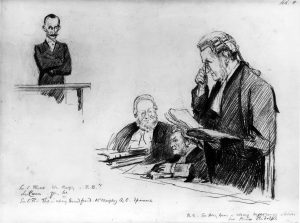

Interest in the courtroom drama reached fever pitch with the cross-examination of the sinister ‘Major Le Caron’, the pseudonym used by the Government Spy, Thomas Miller Beach, who claimed to have infiltrated the Fenian organisation on behalf of the British Government. Drawing on his inherent skills as a caricaturist, Hall laid bare the comic aspect of Beach’s wary performance in court, as the spy ‘rapped out his answers with a sharp metallic twang’ (Legal column, Graphic, 16 February 1889, p. 158). In this work, focusing on the exchange between the edgy witness, with his defensively crossed arms, and his wry interrogator, the barrister Sir Charles Russell, Hall cleverly used the suggestion of the telescoped distance between the protagonists to convey the tense drama of the moment.

A source of popular fascination, the commission attracted a crowd of high profile spectators, including leading actors, authors, painters and dramatists, such as Lord Leighton, Herbert Beerbohm Tree and George Meredith – some of whom came in search of creative inspiration. Signaling the fashionable allure of the case, Hall made portraits of the well-known celebrities he spotted, including this unusual, but compelling view of Oscar Wilde, shown with an air of immediacy as if preoccupied by the proceedings.