Parliamentary Affairs

In 1886, in a column of text accompanying Paul Renouard’s sketch of ‘one of the smoking rooms at the House of Commons in the portion of the building allotted in recent years to the members of the Press’, the Graphic highlighted the growing importance given to ‘the small army of newspaper men who are in nightly attendance as long as the House of Commons is sitting’. Marking a subtle shift in perception that had taken place, the publication commented:

less than ten years ago the reporters received but scant consideration from a House in which their presence was by tradition, and, indeed, according to its rules and orders, nothing less than an intrusion. As Mr Palgrave, the Clerk to the House, says in his little book about the House of Commons, ‘The newspaper reporters are technically and truly “strangers” to the Parliament … Every word the reporters write is a breach of privilege’. But the modern House of Commons is not so antiquated as its own rules, and of late years officials have seen the reasonableness and desirability of helping, instead of hindering, the work of the Press.

(Graphic, 18 September 1886, p.291).

Reporting on parliamentary proceedings had become another routine aspect of the Specials’ portfolio. Akin to the introduction of cameras in the twentieth century, their work allowed unprecedented, vicarious access in graphic form to the daily affairs of parliament – the influence of which upon the court of public opinion has yet to be assessed.

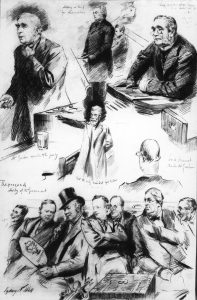

Sydney Prior Hall, like Harry Furniss (who worked in this capacity for the Illustrated London News and Punch), ‘frequently sat for many, many hours, watching every gesture, every change of expression’ made by the leading politicians while engaged in parliamentary debate (Harry Furniss on Gladstone, Pall Mall Budget, 11 October 1888, p. 13). This quick preparatory pencil sketch of the Prime Minister William Gladstone was made by Hall at some unspecified point in 1886 while either observing the debate on the Irish Tenants’ Relief Bill or Gladstone’s defence of his Home Rule Bill. Typical of Hall’s working method, such incidental portrait ‘scraps’ informed the documentary images he supplied to the Graphic and still retain a latent sense of his experience of observing Gladstone in person.

Rather than attempting to capture one representative scene, Hall often arranged a group of these quick vignette sketches into a composite image that worked in aggregate to convey a characteristic impression of the day’s goings-on. In this example Hall’s comic sensibilities came to the fore and he included a moment of levity he’d seen (involving a caricature of Joseph Chamberlain) amongst the frontbenchers after the division on the debate on Indian Cotton Duties – this related to the setting of import and excise duties on Indian cotton, an issue of keen concern to the Lancashire textile industry and Indian Nationalists. Joking apart, the illustration centred on the stern figure of Dadabhai Naoroji, member of the Liberal party and first Indian MP, declaiming the negative effects of the policy on the Indian economy.

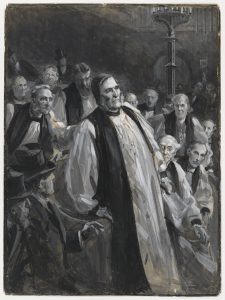

In the 1890s, technological changes saw the half-tone engraving become the preferred method of reproduction in the illustrated press. In response to this development, the artist-reporters provided a more advanced form of the ‘illustrator’s sketch’, worked up in grisaille watercolour to a more finished degree. Demonstrating his journalistic skill, in this powerful sketch, titled ‘The Education Bill in the House of Lords: A Pathetic Incident’, published in the Graphic on 13 December 1902, Hall represented the high drama of the moment when the ailing Archbishop of Canterbury briefly collapsed while vigorously defending the Bill before rallying to finish his point to sympathetic applause. The published version of the dramatic image, which focused attention on the figure of the swaying Archbishop, appeared with the factual account of the incident printed underneath detailing the sequence of events and the relevant, poignant excerpt of his interrupted speech.