A quiet revolution

Covering a wide range of topical events – from engineering innovations, civic affairs, parliamentary debates and judicial inquiries to royal tours, municipal ceremonies and military campaigns at home and abroad – the work of the Specials remains a fundamental, but often overlooked, primary source for the social and cultural history of nineteenth-century Britain. As a new media technology that brought the world closer, shrinking space and time and conveying newspaper readers to distant places, the work of the Specials should be considered as seismic in its cultural impact as the introduction of the railway and telegraph. Excited to be at the forefront of what, even then, they considered a thoroughly modern phenomenon, the Graphic marvelled at the global scale of the visual news access now graphically available to the Victorian reader through the medium of the press:

Moreover, the various portions of the globe are now so closely united by railways, steamships and electric wires, that morning by morning the news of the whole world is almost simultaneously upon our tables, so that we partake, not merely as formerly, in the joys and sorrows of our own fellow islanders, or in those of the small portion of Europe, but in those appertaining to a thousand million of human beings. The intelligence of a terrible flood in China, of a forest fire in America, of an extraordinary discovery of gold or diamonds in the Southern Hemisphere, reaches us at a speed which would have been deemed miraculous within the lifetime of men still living; and thus, with the whole world as a reservoir of astonishing events, no pictorial journalist need never lack subjects for illustration

(‘Preface’, Graphic, Vol. II 1871, p. v).

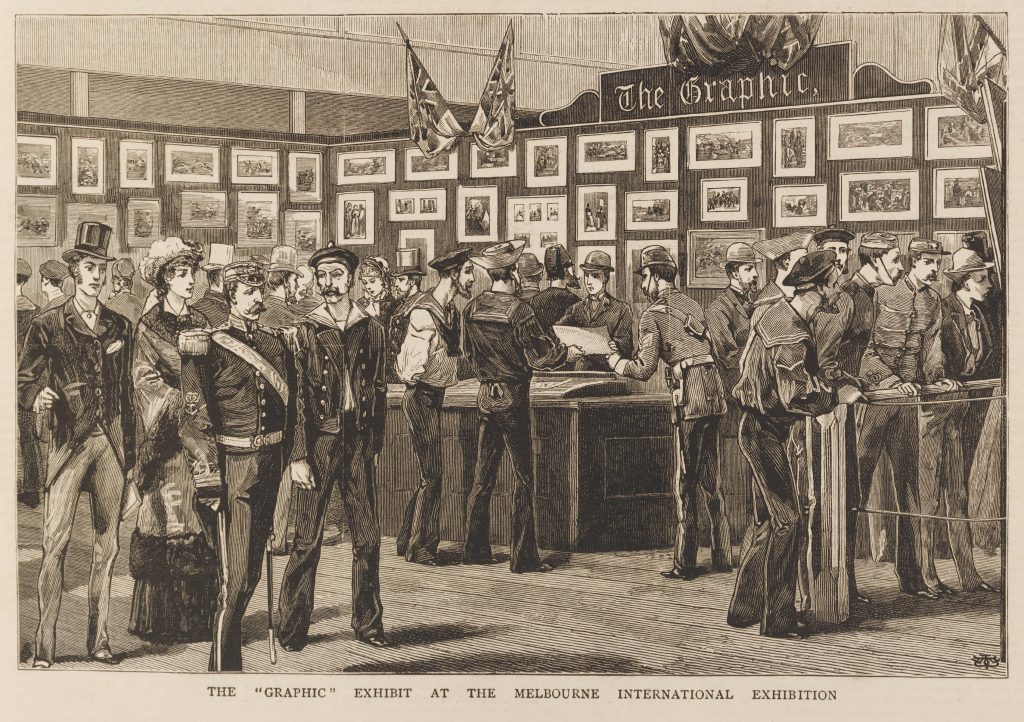

The foundation of a global media network is seen in the dissemination of British journalistic practice via the International Exhibitions that periodically took place over the course of the second half of the nineteenth century. In August 1876, the Graphic reported that it had a section at the American Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia that was ‘intended to show the whole process of producing an illustrated newspaper, from the trunk of the tree whence is obtained the wooden block on which the illustration is drawn and engraved, down to the finished electrotype whence the impression is printed’ (‘Our illustrations’, Graphic, 12 August 1876, pp. 150 & 164). As showcased in this engraving, the newspaper also had a promotional stand at the Melbourne International Exhibition of 1881, with framed examples of the illustrative art of the Specials on view. Talking in particular about the journal he founded, but in a manner that speaks to the impact of Victorian graphic journalism in general, William Luson Thomas, would proudly proclaim:

The success of the Graphic caused the most extraordinary movement. In nearly every country in the world illustrated papers and magazines, started up in all directions, many of them paying us the compliment of copying our illustrations every week, and adding others of local interest– many also, particularly in Spain and Italy, showing great originality and introducing artists of talent to the public

(‘The making of the Graphic’, The Universal Review, 15 September 1888, p. 86).

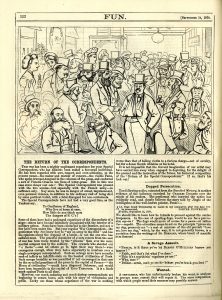

Meanwhile, the fame of the Specials as celebrated individuals in their own day is captured in Fun’s sketch, ‘The Return of the Correspondents’, published to mark their arrival back in England from covering the Franco-Prussian War. Immediately recognisable in the front row is George Augustus Sala (his right arm in a sling), with ‘Labby’ (Henry Labouchere. the ‘besieged resident’ of the Daily News) with the monocle to his right. The fact that readers of Fun could be expected to recognise the Special Correspondents in its sketch bespeaks their status as household names by the 1870s. However, Harry Furniss revealed that although at times extremely popular, this high celebrity of the Specials was fleeting in character:

War correspondents only come to the surface when there is a campaign; for a brief time they enjoy the most exciting experience in journalism. They are ‘it,’ they spend money like princes and return as heroes; they appear on lecture platforms in their war-paint or in evening dress a la Forbes, their coats ablaze with foreign orders, or hanging from ribbons round their neck. They appear in the limelight and are then lost from view until the next war brings them forth again.

(‘War Correspondents and some “Specials”’, My Bohemian Days, 1919, p. 136)

Part of the reason for the lack of recognition of the creative achievements of both branches of the profession in recent times is that they operated across the boundaries separating Victorian art and literature from the developing field of documentary journalism. Thus, although admired for their bravery by their contemporaries, lasting critical success eluded them. It is only by looking back through a retrospective lens that their seminal role in the foundation of a graphic news industry, which forever altered the British public’s field of view, becomes startlingly apparent.