By Professor Jeremy Carrette, University of Kent

In Joachim Radkau’s history of the environmental movement, The Age of Ecology (Polity, 2014), the “revolution” in ecological engagement is seen to be “in and around 1970”, captured by a “cluster” of events that moved conservationist activity into a mass movement. The year 1970, for example, saw the first Earth Day on the 22nd April, the European Conservation Year (originally declared in 1963 by the Council of Europe) and environmental issues featured on the covers of key national magazines such as Time and Der Spiegel. The actions of the 1960s had set these events in motion, the creation of the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) in 1961, the key publication of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring in 1962 and the UNESCO conference on the biosphere in 1968 are three such moments.

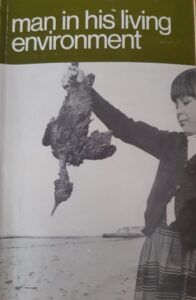

Radkau’s study recognised but chose to ignore the “secret spiritual side” of his “new Green Enlightenment” argument, but 1970 was also important for the roots of Anglican thinking on the environment. Though largely forgotten, the first major report on the environment by the Church of England Board for Social Responsibility, entitled Man in his living environment, was published in 1970; only 80-pages in length but registering the full impact of environmental neglect.

The Board for Social Responsibility of the National Assembly of the Church of England had been invited by the Standing Committee of the Conferences on ‘The Countryside in 1970’ to “convene an ecumenical group to produce a report on the theological, philosophical and ethical bases for the use and conservation of the natural resources of land, air, water and wild life”, with the hope that “a report would help in observation of European Conservation Year 1970” (p.7). The conferences for ‘The Countryside in 1970’ were held in 1963, 1965 and 1970 and their work towards the European Conservation Year were presided over by the Duke of Edinburgh and became key events in the national campaign to change political and religious awareness of environmental issues. The successes of such conservationist work can be seen in Tim Sands’ extensive study Wildlife in Trust: A hundred years of nature conservation (The Wildlife Trust, 2012), though the political battles were extensive and continue in very different ways.

HRH Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, and HRH the Prince of Wales, at the final session of The Countryside in 1970.

The conferences on ‘The Countryside in 1970’ and their importance to the UK can be seen as shifting the political landscape and raising issues for local and international action on the environment. For example, Arthur Blenkinsop (MP for South Shields) raised the issue of the European Conservation Year in Parliament on 10 March 1969 and praised the first two conferences for their “detailed preparatory work”, paying tribute to such key figures as the Duke of Edinburgh and environmentalist Max Nicholson.

Blenkinsop asked whether the Government was “really supporting the venture actively enough” and highlighted that it was “not merely a European matter, but a world matter” (HC Deb 10 March 1969 vol. 779, cc1127-38; Hansard, Commons Sitting, Orders of the Day, api.parliament.uk). Likewise, the Standing Committee of the Conferences on ‘The Countryside in 1970’ had found support in the then Archbishop of Canterbury, Michael Ramsey, the Catholic Archbishop of Westminster and the British Council of Churches to bring together an ecumenical group with the following terms of reference: “To examine and comment upon the ethical basis of man’s use of natural resources, particularly those associated with the living environment”.

Proceedings from the first Conference of The Countryside in 1970.

From Conservation to Climate Change: 1970 to 2021

An ecumenical report from the 1970 Church Assembly Board for Social Responsibility, now over 50 years ago in the Church of England’s history, may seem irrelevant compared to such contemporary mass movement texts as Time to Act (2020) from Christian Climate Action, the Christian wing of Extinction Rebellion, or, indeed, Extinction Rebellion’s own “handbook” for action, This is not a Drill (2019), with the Afterword from former Archbishop Rowan Williams. The environmental crisis has escalated since 1970 and the networks of the Anglican response have in turn become global, with such international reach through the Anglican Communion Environment Network (https://acen.anglicancommunion.org) and groups like Green Anglicans (http://www.greenanglicans.org) in Southern Africa. However, I think there are fascinating historical details and some profound ethical issues in this early institutional statement within Anglican history.

One historical point to mention – in this year of his death – is the fact that we see the important place of Prince Philip, the Duke of Edinburgh, in Anglican thinking on the environment, something that becomes more evident in his work with the Right Rev. Michael Mann, Survival or Extinction: A Christian Attitude to the Environment (Michael Russell Publishing, 1989). Man in his living environment opens with The Duke of Edinburgh’s closing speech at the 1963 ‘The Countryside in 1970’ conference – in words that echo what we now call the Anthropocene – emphasising how the world is “dominated by the works of man [sic]” and the need for a “balance between species and within environments”. There is also a fascinating mention of the University of Kent, because the ecumenical group behind the report included Professor W.A. Whitehouse, the founding Professor of Theology and Religion at the University of Kent in 1965, who is listed in the opening membership pages. Professor Alec Whitehouse (1915-2003), a Congregational minister, was a specialist on science and religion and well-suited for the technical environmental and ethical aspects of the report.

However, it is the wider ethical issues of the report that continue to have important value to environmental thinking. The language of the report illustrates the initial Anglican reception of the new emerging ethical horizon, something seen in the opening words of the Bishop of Leicester: “One result of this report may well be that the word ‘ecology’ becomes more common in Church circles than it has been in the past!” Strikingly, these words have been realised fully in the contemporary activities of A Rocha – the international Christian conservation group founded in Portugal in 1983 – which informs the Anglican network of Eco-churches across the world. The report in this way was a turning point in engaging the Anglican community to act and change minds.

It begins with a recognition of the problem of the human animal – “man” – as the dominant ecological force and the fact the human animal has “not learnt the laws governing balance in nature” and thus faces the destruction that follows (p.13). The political and economic issues are clearly stated: “They too easily plead immediate economic gain and in the process impoverish the earth and destroy what is irreplaceable” (p.17). The report does not begin with detailed theological or philosophical comments, but highlights “specific problems and situations” in order to map the “state of knowledge” on these key environmental subjects (p.9). It addressed a wide range of concerns, covering the treatment of animals, over-population, pesticides, air and water pollution, water resources, the sea and sea-bed, and public attitudes to conservation. Each section discussed the new awareness of complex ecosystems, mismanagement and the need for conservation acts and agreements, providing a strong sense of the relationship with the environment. It was in the final two sections that the ethical issues of the environmental situation were pulled together in ‘A Basis for Judgement’ and ‘Provisions for Vigilance’.

The ethical force is driven with a call for a “cultural revolution in which it is affirmed that despoiling the earth is a blasphemy and not just an error of judgement” (p.61). It seeks a change in “attitude”, where “immediate gains to future good, which restrains economic exploitation to make it a source of enrichment of life, which challenges the cult, though not the fact, of social and industrial efficiency” (p.61). The call for action in the face of disasters and the programme for vigilance makes the last 50 years appear deafening. Embracing science and religious-secular philosophy, the report holds a collective drive to protect the future and does not hold back in questioning the ethical failures of religion: “The record of religious utterance on this vast theme is not spectacular” (p.63). The ethical concern in large part opens questions around a wide variety of theological and evolutionary issues, appealing to Biblical themes as well as Darwinian insights, through Alister Hardy, Julian Huxley and Teilhard de Chardin, to reimagine images of God. It ambitiously brings modern biology into creative dialogue with natural theology to address the “inter-relatedness of living creatures in the physical conditions obtaining on earth” (p.70).

The final section is striking for its final ‘Provisions for Vigilance’, which today serve to underline the failure of that vigilance in the church and the world to listen to the requirements of environmental harmony and balance mapped out in 1970. The summary point of the report is to take action “before it is too late” and to become aware of the consequences of decisions; but looking back – while there have been conservation achievements – we see how environmental issues have now moved tragically from concern to crisis, from conservation to climate emergency. Fifty-years later, we see that there is a different sense of time and urgency and overcoming the blocks to change even more vital. Addressing each of the themes of the report from the treatment of animals to land use, the report recognises the problem of “co-ordination” and the need for “an administrative revolution” to bring forward the ethical judgements through international treaties; something not lost in our contemporary context of the COP26 (Conference of the Parties, the UN climate change conference) gathering in Glasgow this autumn, 2021. It sees the competing interests at play in these decisions, but wisely stressed there must be “power to make and enforce decisions” (p.79). The report still holds power and relevance with these insights.

Man in his living environment is an extraordinary moment in Anglican environmental thought. It confirms 1970 as a threshold in environmental history, but also reveals a radical opening of the agenda that shaped the future Anglican contribution and the challenge to change attitudes and reshape Anglican ethical and theological concerns. The report draws attention to the underlying ethical neglect that results in the environmental devastation: “Man [sic] loses proper control over nature by losing control of his [sic] own morality” (p.63). The Anglican challenge over the next 50 years was to reshape the ethical and theological imagination, but that challenge continues for all the same reasons the report states of “avarice, greed, [and] pride” that “destroy the earth” and which are clearly not the ethical purpose of life (p.63).

The image selected for the cover of Man in his living environment captures well the overriding moral concern: a small child holding up a dead sea bird from the oil-slick waters. Here – in visual form – is the Swedish Environmental activist Greta Thunberg’s ethical challenge to the world, the responsibility and ultimate accountability of those in power to protect the earth for future generations (see Thunberg No One is Too Small to Make a Difference, Penguin, 2019). Returning to Anglican moral engagements on the environment in 1970 is a salient historical and ethical exercise, because it underlines the urgency of the task and the dangers of forgetting the ethical vigilance of such reports.

Jeremy Carrette is Professor of Philosophy, Religion & Culture and is presently carrying out research into the history and ethical philosophy of Anglican environmental thinking.