The Light in my Room (An-Nuur fii ghurfatii)

I write in a white, rectangular corner of our flat, which I hammered together without denting the pressboard surfaces or crushing my thumbs overmuch. The walls are white, too. I get up early to write. The large windows beside and behind me look over the Don River, over Corporation Street–really, you have to wonder about those Sheffield street-namers (Inequality Street, Tax-haven Street, anyone?)–and up a forested hill, a mass of jumbled darkness. And then light begins to do its work: the hill, as the sun emerges, reveals its tumbling and luxurious green leaves; the river flows in a pattern of whitish wavelets and surface flexes like fragmenting chevrons. I can see the mortar rictus around each brick in Aislewood’s Mill, and then the sun, briefly, hides behind the Mill’s old chimney. I can turn off the overhead fluorescent lights now and dumb down the shadows so the motion of my hand, say, is not so obviously ulterior and my face and shoulders are not lurking in my screen.

I haven’t written a word yet.

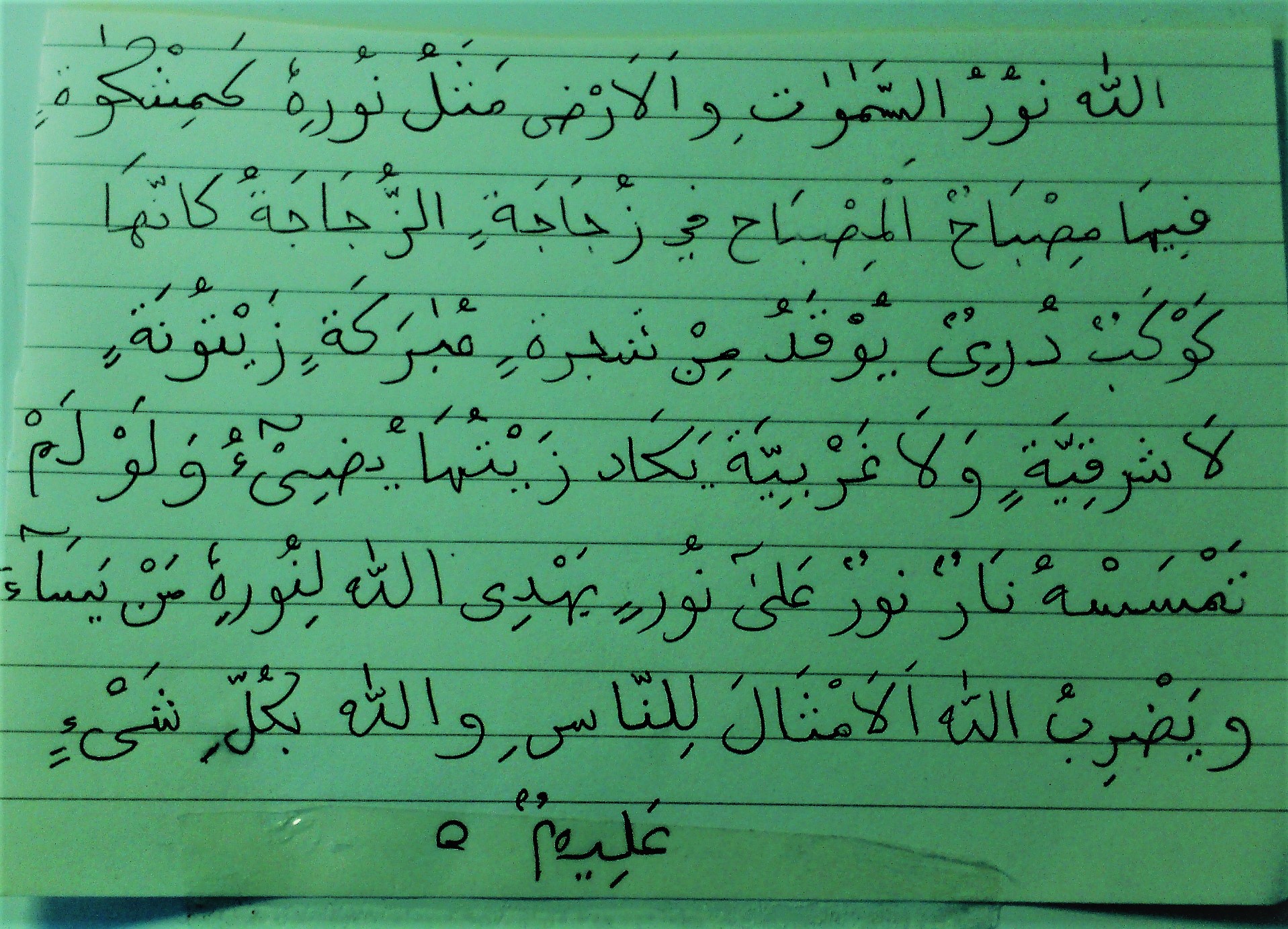

Above my computer, (see attached photo) I have taped a handwritten verse from the Qur’an, the Light Verse (24:35). I have been writing poetry lately, and mulling over the various inadequacies of metaphor, so I look to this verse as corrective and inspiration, as I believe it suggests much about creativity. I know you may not be a believer of any kind, so I hope you will accept “Allah” in the verse to mean an inconceivably huge creative force, connecting everything. In the verse, the light of Allah is compared to a lamp, in a glass, in a niche, and the glass to a shining star kindled from a blessed tree, whose oil is from neither the East nor West but is just on the brink of luminescence, though fire has not touched it.

Much has been written about this verse’s spiritual implications, but I think its movement also suggests what goes on when writers achieve their breakthroughs. I love the chaining spontaneity of this rush of comparisons–light, niche, lamp, star, tree, oil–and the stately parade of Ks in the Arabic (kaamishkatin, ka’innaha, kawkabun, mubaarakatin, yakaad). There’s a nice refusal of the fuel’s source, pointing to a mysterious, absolute perfusion. The images come fluently, with nothing so clanking as a causal chain. This is what we hope to access. May the light sweep our intentions aside, ahead, and along, and lead us where it will.

But I am no enlightened mystic. I struggle to find the light. I am trying to write a poem about a bygone Manitoba farm, whose dawn begins with a distant silver rind on the secondary highway, a pale sheen on the steel oil-tank. Then the light reveals the diagonal printing on an outbuilding’s buffalo-board, the glint of its chicken-wire mesh. The spray of dried mud above a pickup truck’s wheel-wells. The specks of chicken feed scattered in the gravel…

I will just look at the Arabic a little longer. Then I will begin, in sha’a Allah.

Steve Noyes is a novelist and poet living in Sheffield.

Website: www.stevenoyes.com