“One-step-back” mode: GCDC research in 2020

“We have an ancient and quite famous ritual in the South Italian region where I was born. During the Easter week procession in Taranto, men in hooded outfits carry the statues of the Passion of Christ, but they don’t walk at an average pace. They perform what we call the Passo del Perdono – the walk of forgiveness: two steps forward, one step back. Nothing better than this gesture, two steps ahead, one step back, encapsulates what it feels like working on a GCRF research project in the middle (or perhaps in the tail) of a long pandemic. Then again, it is not an exercise in forgiveness, but about acceptance, endurance, and, it may sound sentimental, about attention.

I completed my PhD at Kent in May 2020 and begin working on the post-doc straight after, with the help of my former supervisor Michael Newall and filmmaker Richard Misek from the School of Arts. My project, Acting before the Emergency, focuses on how art can educate people to prevent or cope with climate-related disasters in Brazil. In the last year, the Coronavirus outbreak has side-stepped climate change as an urgent concern internationally. Corporations that until a few months ago were committed to environmental issues have begun putting their “greenwashing” commitments aside with the excuse of financial survival (see article). The situation in Brazil, however, was already quite worrying even before Covid-19.

As he came into office in 2018, Brazilian right-wing president Jair Bolsonaro began a process of deregulation of environmental policies, including devolving power of the IBAMA (Brazilian Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources), and passing laws that legitimised “land grabbing” in the Amazon. According to Reuters, “deforestation hit an 11-year high last year and has increased 55% in the first four months of 2020.”

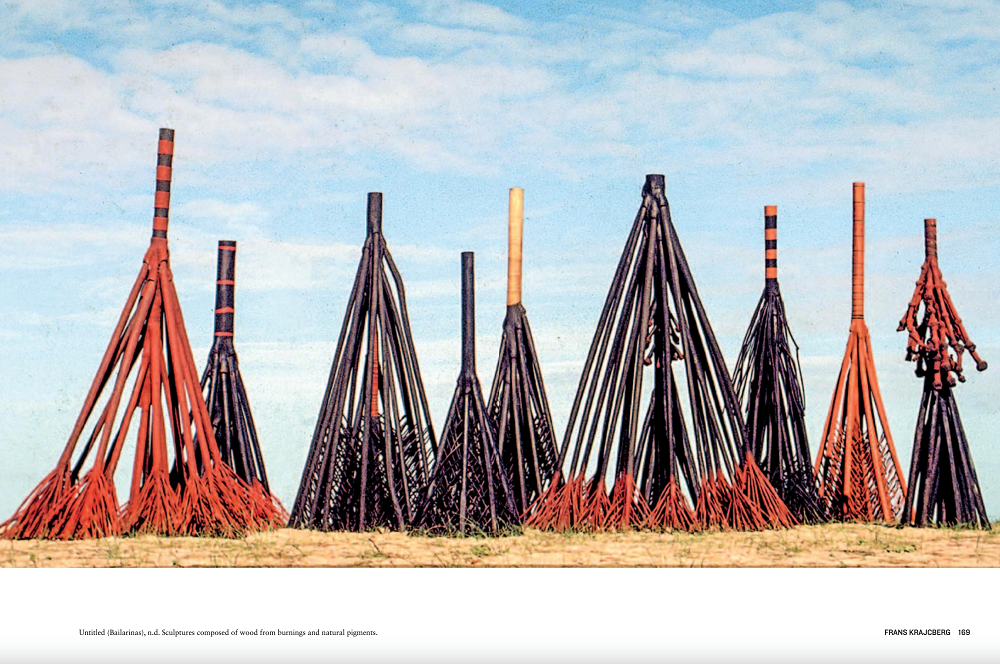

A page from the 2016 San Paolo Biennial with Frans Krajcberg’s work Untitled (Bailarinas) (32bienal.org.br)

The situation was radically different before. In only 2014, the international community had hailed Brazil’s environmental policies as a world-leading example to follow. Not only did the country register the lowest record of fires in the Amazon, but a report from a UKRI-funded project concluded that people were exceptionally sympathetic towards the issue of climate change (link). In 2016, the San Paolo Biennial – one of the world’s most acclaimed art manifestations – exhibited several ecologically-minded works. Titled Incerteza Viva – Live Uncertainty, it capitalised on a long-standing tradition of earth-art in the country, with artists such as Bene Fontaneles, Erika Verzutti, Maria Teresa Alvez and Frans Krajcberg. Two years later, the new president came into office.

An Instagram post by Brazilian artist Uyra Sodoma

For the above reasons, my research focuses on how climate-related disasters feature in the art produced or exhibited in Brazil over these last two crucial years. It is not about activist art, nor about sublime “disasters” – or at least not only. The research instead is an attempt to map out how art operates across different modes of engagement as opposed to media and activist narratives, and how these modes of engagement can help us understand and think about climate change differently. I see art as a resource for sensing and thinking about the threatened planet, and promised realities. I am thinking of Uýra Sodoma, the Amazonian drag queen-biologist who uses performance to educate young people to protect the Amazon. Or about filmmaker Ana Vaz, whose film Apiyemiyekî? (2019) is currently on show at the ICA in London. These artists demonstrate how climate change is intrinsically connected to the practices of justice, equity and sustainability in everyday life – they understand climate change from a very regional perspective. Hopefully, these and other works will feed into an educational, accessible resource for climate change educators that will not just present examples of best practice, but contribute to strengthening the links between the networks of artistic production and those of climate change outreach in Brazil and internationally.

The poster from Apiyemiyekî?, dir. Ana Vaz, 27min, 2020

The most challenging aspect of working on this project has been to question if it could ever make any difference in the larger scheme of things. Working alone in a child’s bedroom, I have been waiting for emails, answers, or Zoom meetings with someone on the other side of the world. It is hard to maintain realism in a project like this. It seems as if the whole world as I know it is engaged in a collective effort of self-reflection and mea culpa, stuck in a massive one-step-back mode just like in the Taranto procession. Luckily for me, these moments don’t last forever but are perhaps necessary to take, as philosopher Isabelle Stengers argues, a pace of slow attention. Maybe it is when I take a step back that I am moving forward.”