By Violetta Ritz, GCDC Doctoral Candidate, School of Politics and International Relations

‘1.5 degrees is not just a target, but a necessary precondition to our continued existence.’

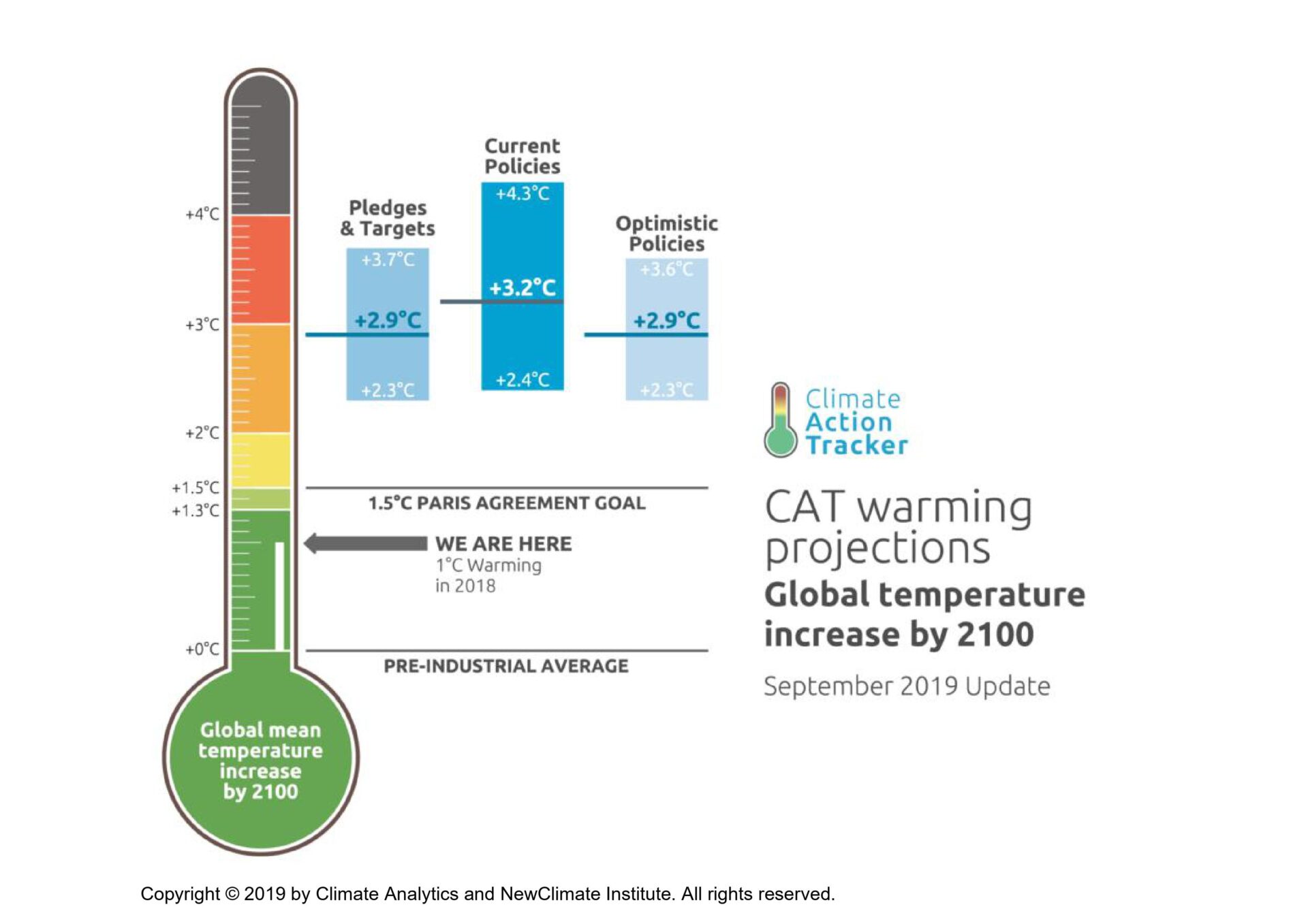

Milagros De Camps’ words spoken on behalf of the Alliance of Small Island States at COP 26 ring in my head while reading the Climate Action Tracker’s global update released in the same week as De Camps’ delivered her speech in Glasgow. The Tracker estimates that present-day policies put us on track for a temperature rise of 2.7°C by 2100. ‘Even with all new Glasgow pledges for 2030, we will emit roughly twice as much in 2030 as required for 1.5°,’ the Tracker finds.

Given the insufficiency of governments’ current measures to meet the Paris temperature target, lawsuits around the world have been mounting pressure on states to close what the Tracker terms ‘the credibility gap’. States’ acts adding to global warming can classify as a violation of their legal obligations. While this argument is gaining ground before judicial bodies worldwide, the UN Human Rights Committee passed a resolution in October ‘recognis[ing] (…), for the first time, that having a clean, healthy and sustainable environment is a human right’. The wheels of climate justice are turning. There is, however, one trying question that judges worldwide are facing: What exact level of emissions reduction is due from individual states for them to conform with their legal obligations?

During my time at the GCDC, I have endeavoured to contribute to tackling this question. In an article which is forthcoming in Transnational Environmental Law, I analyse the evaluation of states’ greenhouse gas emissions by the Climate Action Tracker through a legal lens. The Climate Action Tracker is a database maintained by climate scientists and policy analysts from the NewClimate Institute and Climate Analytics in collaboration with the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. The Tracker assesses states’ climate action against the Paris temperature target and ranks countries into different categories ranging from critically insufficient to 1.5 Paris Agreement compatible. As of now, no country is ranked in the latter category, and more than half of the countries covered by the Tracker are rated as highly or critically insufficient. The results of my interdisciplinary research suggest that the so-called PRIMAP Equity tool, used by the Tracker, is the best available method to distribute a global carbon budget among states in accordance with equity criteria recognised by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). The PRIMAP Equity tool allows for such a transparent and comprehensive operationalization of the equity principle enshrined in the international legal regime on climate change that is it to be considered apt for legal use.

The main question that lies ahead concerns the size of the global carbon budget. This hinges on the global temperature pathway to be pursued and at what likelihood. Controversies exist over the legal bindingness of the Paris temperature target. Therefore, even if not as strong as many hoped for, the ‘resol[ution] to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C’ in the Glasgow Climate Pact is important as is the UN Human Rights Committee’s recognition of the human right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment. The first part of the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report released in August stresses that even global warming of 1.5°C will cause events unseen in the ‘observational record’ and that any further increment in warming will aggravate these events and increase the likelihood of climate tipping points being triggered. Against this backdrop, a strong argument is crystallising that preventing global warming above 1.5°C is vital for small island states and it is vital for life on earth as we know it. It’s not just about ‘keep[ing] 1.5 alive’. It’s about keeping what we love alive.