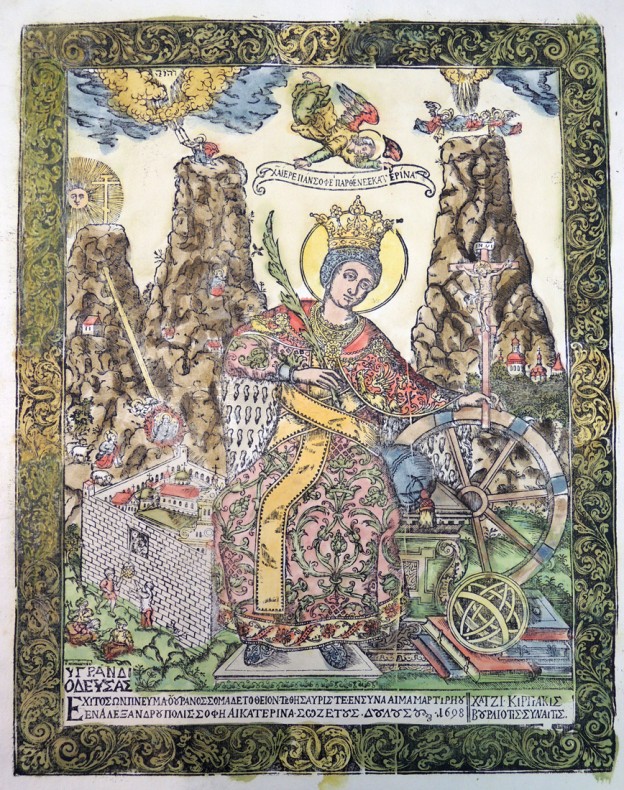

A woodcut print of St. Catherine produced in the region around Lviv in 1698 offers an insight into the invention and dissemination of an image with origins from the eastern Mediterranean and the Jordanian desert and later currency in the northern and southern regions of central and eastern Europe.

St Catherine in Lviv, 1698: the trans-national translation of an image from Crete and Sinai to Samokov via Lviv

By Claire Brisby, London

[1. St. Catherine of Sinai, Nikodimos 1698 ill. Papastratos, D, Χαρτινεσ Εικονεσ Ορθοδοχα Χαρακτικα 1660-1899 (1986) 401]

The woodcut print was published with the inscription Nikodimo rokou 1698, which names the engraver and emphasise the year of production at the end of the seventeenth century, ‘rokou’ being the old Ukrainian word for year (similar to Polish). The Polish language situates the production in a Polish-speaking context and the engraver has been identified as Nikodim/Nikodem Zubrzycki (Zubrytskyj), known to have been active in the period 1688-1724 in region of Lviv (he signed his works in Ukrainian and Polish), now in western Ukraine. The woodcut dates from the period of this engraver’s activity at the Orthodox Krehiv (Krechów) Monastery between 1688 and 1702.

The woodcut print is one of several by Nikodim representing St. Catherine with the iconography of the saint which had been inaugurated in Orthodox Christianity earlier in the century by an icon at the Monastery of St. Catherine in Sinai. Installed in the royal register of the iconostasis in 1612, the icon is inscribed to name a monk from Athos Palladas/Pallados and an active painter during the first half of the century; the additional inscribed name of Jeremiah from Heraklion anchors the icon’s production before 1612 to Crete.

Palladas’ icon manifests a considerable re-invention of the standard iconography of the saint, tailored to the venerable Orthodox monastery named after the saint at Sinai. The saint is pictured before the stylised three Biblical peaks of Sinai, with an image of the monastery itself in the lower left part of the landscape setting. Palladas presents the saint seated beside an astrolabe and several volumes of books, to represent the saint’s academic learning which sustained her refutation of the Christian faith leading to her martyrdom. This female representation of Christian faith and constancy attributed to rational erudition fuses religious piety with the scholarly erudition that was promoted in western cults of the saint. Moreover, the innovative visualisation of the monastery renowned in the Christian sphere since the Crusader’s intervention and patronal adoption of the saint enshrined in her miraculous translation from the west, endowed the environment of Biblical Old Testament revelation to the prophets Moses and Elijah with topographical veracity. The formation of Palladas’ subject and imagery synthesising theological piety with Enlightenment philosophy and integrating hybrid western approaches to representation reflect absorption of diverse ideologies from the multi-cultural context of the icon’s production in Venetian Crete.

Nikodim’s treatment of Palladas’ image of St. Catherine almost a century later demonstrates the enduring prevalence of the iconography as well as the status of Lviv as a prominent cultural centre responding to artistic and academic currents from east and west. It manifests the city’s importance as a centre of print production, responding to the patronage of multidenominational patrons, including from the Greek Orthodox mercantile community. An ordained deacon of the Orthodox Church and an active engraver at Basilian monastic institutions, Nikodim’s engagement with the Greek Orthodox iconography of St. Catherine had predated the series of prints by a decade, according to the only icon attributed to him inscribed 1688 surviving at the Vatopedi Monastery on Athos. His series of St. Catherine woodcuts were commissioned by HatziKyriakis from Vourla, near Ephesus in Asia Minor, with personal contacts with the Monastery of St. Catherine on Sinai. HatziKiriakis is known to have patronised another figure, Dionysius, and to have been personally responsible for supplying the printing workshop with materials, specifically paper and ink, and for a methodical distribution of prints. A copy of the woodcut with a variant inscription survives in Lviv and several woodblocks, together with some hand-coloured impressions preserved at the Sinai monastery, attest to their dispatch eastwards.

Nikodim’s woodcut prints of St. Catherine have continued to circulate afield, as evidenced in the examples preserved at the Princeton University Library – exceptionally, coloured, and in the Library of the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences in Sofia.

[2. Nikodim Zybrzycki (Zubzritski), St Catherine of Sinai, hand-coloured woodcut, 370 x 280 mm (Princeton, NJ, Princton University Art Museum) Inv. GA 2014.00010; J. L. Mellby, ‘Paper Icons Made for the Monastery of Saint Catherine, Sinai’, 2014, online: https://graphicarts.princeton.edu/2014/01/21/paper-icons-made-for-the-monastery-ofsaint-catherine-sinai/]

Moreover in Bulgaria, the stencil pricked to scale with the image of the woodcut of St. Catherine inscribed ‘Nikodimo rokou 1698’ which survives in a nineteenth-century workshop archive from painters in Samokov manifests the role of Nikodimos’ prints disseminating imagery in practical terms through their reception as templates for reproduction.

[3. Pin-pricked outline of St Catherine of Sinai by Nikodim Zybrzyski or Zubzryski, 370 x 280 mm, Sofia, National Art Gallery, Samokov Archive II 743.]

The staining of charcoal dusting bears witness to the intermediary function of the stencil in the transfer of imagery. The Samokov painters’ archive also preserves a series of drawings of the Apocalypse after Nikodim’s prints of the subject published in 1717 in Chernihiv, evidencing their debt to northern central European prints and the enduring agency of Nikodim’s work and of Palladas’ model image. Active during the period of the National Revival, the Samokov painters are in turn renowned for innovative interpretations of imagery as Palladas in Crete and Nikodim in Lviv had done for Sinai before them.

Bibliography

Claire Brisby, ‘Orthodox Prints in the Samokov Painters’ Archive’, Print Quarterly, vol.

XXXVIII, no. 2 (2021) pp.131-153; 132, cat 39.

Manolis Chatzidakis, ‘Μιά εἰκόνα ἀφιερωμένη στό Σινά,’ in Ἀφιέρωμα είς Κ. Ἂμαντον,

Athens, 1940, pp. 351-364.