Robert & Peter Chandler

About

| Farmer’s name | Robert Chandler & Peter Chandler (nephew) |

| Age | 94 (Robert) |

| Location | Chandler and Dunn, Lower Goldstone Farm, Ash |

| Size | 1482 acres |

| Type | Mixed |

Interviewed by: Louise Rasmussen

Filmed by: Joe Spence

Date: 12 July 2015

Transcript

(Robert Chandler taking paper and notes out of an envelope)

Louise: Did you make notes for today?

Robert: Well I just made just a few headings. I mean, we can start off…if we go back to the, to the 1920s say when farming changed from horses to tractors. That took place during the 1920s and the, you know the earlier tractors were, like the earlier cars, unsophisticated, that was a big change of course. And then we go on from there.

Louise: Right.

Robert: So…and then of course the next big step with tractors was the Ferguson system being introduced. Do you remember the Ferguson system? He…was he, he was English, wasn’t he?

Peter: Basically the Ferguson system was a tractor but they also manufactured all the implements for that tractor. So that they all fitted that one tractor and the cultivators and the ploughs and a whole range of implements so it wasn’t …

Robert: See, they introduced hydraulics to tractors and other…and whereas, prior to that, tractors had pulled horse implements. You see instead of having a couple of horses or three horses on a thing you pulled it with a tractor. But once the Ferguson system came the implements tended to be fixed to the tractor. And so, you know if you wanted to move from one field to the other you could do that quite easily you know, cause you could, you used to pick it up and go away with it.

L: How did that influence your working days on the farm?…I can imagine it became a lot easier, but…

R: Yes, well, yes, yes, it got, of course it was easier yes. And then of course as we went along tractors got much more sophisticated, you know, we started off just sitting in the open on an old iron seat with a bag of straw and then we had, you know, soft cushion seats and then we had cabs and then we had air conditioning and, you know, to get where we are now, and now of course with satellites tractors and combines and things steer themselves.

P: Basically now with modern technology, as Robert says, the combine or a tractor you can put it in a field and ok, the operator turns at the end but you can, it can drive a straight line and you can take your hands off the steering wheel. And it, by the satellite navigation, it will just drive a straight line. Now, from many farming ways that’s actually more efficient cause with a combine, if you’ve got a header that’s 30 foot wide, when you’re sitting in the middle and you’re looking out, if you miss, like 6 inches, you’re actually under-utilizing the header. Whereas with satellite navigation, it actually makes sure that there’s no real overlap, and the guy on our farm, he’s got it on one, he can go once down a field, go 3 or 4 widths of that machine over, knowing that when he comes back, when he’s done a couple of ends it will actually work the ground to the width of that machine rather than years ago, you’d go well, I think I’m about right, and you might have been either have a little strip left or, you know, what they call overlapping. So technology is coming into farming dramatically.

R: And of course the advent of the combine, which really started in the Second World War and there were a few came in from America during the Second World War, and you see prior to that we cut corn with a, what we called a self-binder. You went round and round the field with a…I got some pictures of it, but it cut the corn, tied it into a bundle and pitched it out at the side. And then you had to have men out there who, or girls, who collected the ten sheaves together, and made what we call a shock. You know, you piled two together like that and then four on each side of them. And then of course the next thing to do was to, you had to cart them to the stack yard on a, some sort of trailer or a wagon and then after that you thatched the stack, and then you had to thresh it during the winter. See, once the combine came, it did all that in the field; it cut it and threshed it and initially it put the corn into a bag, and much to by annoyance a bag was up nice and high on the combine and it slid down a chute under the ground. So the poor chap who came by and had to pick it up put it on a trailer, which always annoyed me cause I was that poor old chap. And so you went into the barn with a whole lot of bags. All your corn in bags. But then of course it wasn’t long before the combines had a tank on them and it went into the tank, and we, then we had a trailer, a nice, high sided trailer, typical trailer, and you’d run alongside the combine and as it was still combining, the corn came out of a chute into a vehicle or a trailer or lorry or something. And then of course we went to grain harvesters at Wingham who had a sort of central grain storage system, you know, individual farmers, some, the bigger farmers did that, but us small peoples, relatively small corn growers, we, you know, we couldn’t afford the capital outlay but they had this, so I had an old army lorry and I used to get it loaded and nip off to Wingham with it you see. And then hopefully get back before we’d got another tank full.

P: So I think, I think like anything, technology, I mean there’s been a huge change in technology equipment, machinery, and as a result of the change from horses to tractors, and from a bagging combine to a combine that we have now is just that the output and the number of people employed on the farm.

R: Yes exactly, yes, cause all these…as we went along so you needed less and less people because another thing that came in soon after this was the crop sprayer. We had, we could spray for weeds. You see, instead of, whereas we used to have a whole lot of people hoeing potatoes and walking through corn, stubbing out the thistles, now it was all done with a sprayer, and a selective weed killer. So that was a big step forward, but also it meant, you tended to need less people. And then, the next, well one of the next things really was the plant breeders. When I started we were satisfied with one and a half tons of wheat or my father was, one and a half tons of wheat to the acre. But once combines came, and the corn used to grow quite high, you know it was up, almost shoulder high, a variety like Red Standard, but once the combines came, you see, they didn’t want too much straw because it slowed them down cause it had to get all through, wind through them. So if you were little short stuff, that, that…you see. So the breeders tended to get short of a shorter straw, but bigger ears, somehow, and so within a matter of 20 years, crops shot up from about 1,5 tons to the acre to about 4 tons, which was quite a big step up.

P: There’s no doubt that breeding, it doesn’t matter if it’s on cereals or even on apples, that the varieties we’re growing now consistently crop much better than the ones back, you know, 50 years ago. Especially on cereals and because it’s an annual crop, you can actually get a fairly reasonable, you can introduce a new variety quite quickly. And so breeding has been quite a huge part of…there are quite a lot of, a lot of money spent on, in research stations over the years on breeding new varieties, but not only are they trying to breed for crop, for volume, they’re also trying to breed so that, they’re trying to breed in a certain amount of resistance to certain diseases. And especially now, that’s become an even bigger issue because – love it or hate it – the chemical debate is here. We’re finding now that the number of chemicals available to us is going down quite dramatically, but the pest and disease pressure is still there. And if…it won’t go away because Nature’s very good at adapting itself, so what might have been a major pest or disease many years ago may not be so crucial now, but something else has come in and taken its place. As you can see, I mean, as you likely read in the press, GM has become a big…And, it’s a difficult one: I can understand the people, that they were worried that we’d get 3 eyed fish and everything else if…But that’s taking genes out of different, you know, animals and putting it into something completely different. I think now a lot of the work is, certainly abroad, is looking at if potato blight for example, which can be a major problem, shall we say mildew and scab in apples can be a major problem, it’s certainly abroad, they’re looking at is there a gene in another apple variety that you can take out. It could be done by, over many, many years, trying to breed that gene into an apple variety. It’s a hot topic and always will be. But we have to feed the world somehow, so it’s…and I have a brother in Canada and the oilseed rape over there is nearly all GM.

R: Yes, it’s odd that the English people won’t have GM, in fact where trial plots have been grown, if these antis hear about it, they’ll go and pull it all up.

P: I don’t know if you’ve read in the press; not long ago, I think in the last few months, one of the research stations over here or research body, I mean the cost of the actual the…research into the trying to breed a certain thing into a… I think it was wheat, was surpassed by the fact that it cost God knows how many million to keep the security up. And I like to think it’s a balance, where do we go? But from the apple front here, well, I don’t know when the first cold…when did the first cold…years and years ago, apples were just stored, barn stored, picked and put into a barn and stored. Robert the first cold store went in?

R: 1930

P: So that was a cold st…

R: The second one in 1934. And I remember my father saying that in 1930 when he put the apples, we put them in bushel boxes, he put bushel boxes in the cold store. When it went in they were worth a shilling a bushel, when they came out they were sold for 9 shillings and he was … (laughing) highly delighted.

P : So that just shows how, you know how things, from the 19…ok then again 1930s, but that showed how a, just by cooling apples, these days, not only do we cool them, but we also control the gas levels that the oxygen and the carbon dioxide in the stores, and now we…so we went from what they called just cold storage to say a controlled atmosphere, and we’re now at ultra…what we call ultra-low controls, so we may run a store; you’re breathing 21% oxygen at the moment, in the middle of winter, some of my apples might breathe 1%. But that technology has literally come over many years, because I now have to have a, like a computerised sampling machine that, I can’t go in and check the apples, that’s too dangerous, I’d die literally within a breath, because it’s at 1%, I’d just pass out. So we have to monitor the gas levels within that store remotely, and I’m reliant on a specialist bit of monitoring kit to say this is the level, and it will open and close valves to maintain that level because we’re now trying to store fruit, shall we say longer, but also the final consumer, you, don’t want apples with a yellow background, they don’t want it a little bit shrively. So the expectation of the final consumer has gone up.

R: When I was trying to do all this control, we used to do it by hand. You know, you opened a valve with just a fraction you see, and sometimes you opened it too much, so that, you know, we never really, if you looked at our results, they’re a bit, little bit like you see, up and down, up and down, so that we didn’t – although it helped – we didn’t get the, sort of efficiency that we get now with these where they’re monitoring, being monitored all the time, and we only…we had a monitor by hand. So only did it sort of morning, midday and evening and it was left all night on its own, and so when you went in the morning you were surprised to see the oxygen had gone up, or there was hardly any oxygen there at all! But…you now, so electronics in a way have been quite a big step forward I think.

P: So the stages basically were; no cold storage and just outside in a barn, cold storage, so just like a fridge, and then shall we say simplified control, so manual effectively, manual control of the store gasses, and now we’re into very kind of detailed, kind of computer controlled, very sensitive monitoring equipment.

Joe: Is that technology affordable for every farmer?

P: I think now if you want to store certain varieties for, until February, March, it’s effectively the only way to go. You don’t need such good stored if you’re gonna go say in…if you’re picking in September, October and you’re gonna sell in November, December, but once you want to go afterwards…But as a farm here we are using a marketing agent to sell our fruit, and we’re working as a group so I don’t open a store, my neighbour doesn’t open a store and someone in West Kent opens, so we got three stores open at the same time and so we gotta sell them all, and then you’re kind of a bit of supply and demand cause if there’s too much being offered, then obviously the price can go down. So we’re trying to effectively store it as long as possible; if it comes earlier than was originally planned, it’s not a problem. But what you can’t do is kind of hold it, if it was destined for December, you can’t suddenly say well actually I wanna get it out in February. And also with the fruit the thing that’s changed dramatically is in Robert’s day a lot of the fruit went up to the local markets.

R: Yes, well, one can argue about this I think, because the advent of the supermarket meant that all the little shops disappear. And so years ago, we would, say, pick strawberries, we used to get up at half past 4 and pick strawberries, and the chap would pick ‘em up at 8 o’clock and take ‘em up to Ramsgate or Margate, and then people could have them the same day! Well now, if they go into these supermarket things, it has to go through the system, so it probably takes, well how long does it take, Peter? It probably takes sort of 3 or 4 days…

P: With apples it’s longer, with strawberries that they can pick today it’s gone out tonight, picked this morning and it’s gone out tonight, but it means it’s not delivered into supermarket until tomorrow. So yes it’s…shelf life, there’s no doubt that shelf life also, the expectation of the consumer today, shelf life is expected to be much longer. Seasons don’t exist. 50 years ago, we picked strawberries, what I call main crop in June, and so you had, I mean Wimbledon used to be the prime kind of June, and people used to stretch it with certain varieties into July, and that was the strawberry season. And now you can buy strawberries 12 months a year. They’re not always English, but they, people will ship in, it’s the same like with a lot of vegetables, you know, you can buy, I don’t know, mange-tout now, which you couldn’t have…And all kinds of other vegetables, which maybe come in from Africa or I don’t know, Southern hemisphere. Apples, there wasn’t really any Southern hemisphere kind of apple coming in at the time, wasn’t being imported, so they just got used to the English and then things used to finish and you’d go on to something else.

R: Another…going back to the sort of a bit earlier, the things that altered agriculture to a degree, I think the government introduced an advisory service, which was free to the user, and if you had a problem, you know, you could phone up and a chap would come out and give you advice. He’d look at the thing and so on. I think that was quite a help to poor old farmers who perhaps weren’t so highly educated as they are now. L: Does this service not exist anymore?

P: We can buy advice, there are various advisers out there but we have to physically buy, whereas years ago there used to be a government advisory body, and so it was effectively a government organisation that would, as Robert said, if you’d got a problem you could approach them and they would come out and give advice on that particular subject. Now I suppose like a lot of things is the cost so it then used to be ADAS so it turned into ADAS over the years, and that’s now been, has had to become a, effectively a commercial organisation. So as a business now, we can go and buy growing or advice from effectively where we want, and there are various advisory groups out there, doesn’t matter if it’s on cereals or fruit or…cattle or whatever. You can go and buy the advice if you want to. But it’s a commercial world.

R: So yeah, I mean I have to admit to being retired for something over 20 years, so I mean, I’m thought to be out-of-date now, but it seems to me in some ways that you haven’t got the outlets for your commodities, whatever you’re growing, there’s no…the number of buyers is reduced, I mean the millers have all got together, there’s only about 4 millers in the country, so I mean they all get together and say right that’s the price chaps. But years ago we had a little mill in Ashford, one in Ramsgate, you know, and you could…And the same with… you know, we could sell to commission agents. I mean we’d have a couple of commission agents in London another one in Leeds, Newcastle, Edinburgh, Bristol. You know, and we could…Leeds was a very good one, you know, and I think it made it more interesting really.

P: So fruit used to go through what I call a wholesale market, and obviously they were then supplying your traditional green grocer. Now as Robert quite rightly says, the traditional green grocers, there are some are still about, but their number is dramatically reduced because the supermarkets have come in and effectively taken over most of the market. Now, not only is it for kind of fresh produce, it’s for all kinds of, you’ve only gotta look at Tesco’s, ok, their figures recently aren’t too good, but they’ve gone into non-foods, they’ve gone into clothes, they went into white goods so you know washing machines and all kinds of electricals et cetera, and because their buying power is so huge, and realistically, love ‘em or hate ‘em, we have to deal with the supermarkets.

L: So how do you have to sell your produce today compared to how you used to sell it?

P: With apples, we now use a marketing agent whereas years ago a lot of it was done as Chandler and Dunn to these commission agents up in the wholesale markets or locally to local, secondary wholesalers, so he’d come and pick it up with a lorry and…

R: See what you could do, I mean what we used to do long before Peter had anything to do with it for instance, we got a bit of a name. There used to be a thing called the Imperial Fruit Show, and that…My father and uncle started showing, which brought our name before a whole lot of people, you see…commission agents. And so there was a time when we sold quite a lot of stuff in Newark because, or Nottingham because Nottingham was a thriving place in those days; it had a big bicycle industry, it had Boots the chemists, it was full of lot of girls there used to buy all sorts of things that we could provide. I think that, you know…although the trade went up, and if you got a quality product or got a bit of a name, you very often sold yours when the other people didn’t sell theirs. You know, you were known. And I think that’s quite important really. Now, you see, the, I suppose, Chandler and Dunn doesn’t count for anything does it?

P: I mean now, if you go and buy apples in a supermarket it’s in a Tesco bag or a Sainsbury bag or whatever. If you go on to the continent, they’re still very much…the supermarkets there are not so big and strong. They’re beginning to get so, and so you can still sell in a…your own named bag. Now, what they do over here is that it’ll be in a Tesco or supermarket bag and some of them will want the name of the grower on it, but it, you know, with all due respect, people aren’t going rifling through the shelves of Sainsbury’s to find a pack that says Peter Chandler rather than, I don’t know, you know, Fred Flintstone’s or whatever, cause basically on the shelf it’s maybe all from me today and from another grower in two day’s time. So yes the name, there’s no doubt years ago, because you were dealing with a lot more buyers, and smaller companies you got, you had a reputation as a grower of, I don’t know, fine produce or maybe, you know, not so fine and so yes, if you were known for good produce, normally, you know, that was the stuff that sold first. If I try and put, say, fruit onto a wholesale market and I’d like to think mine’s quite good, but someone else is putting some poorer stuff, normally now, even these days, the better stuff will sell first as it’ll move, because the customer will come and go well, actually that looks better than that, so I’m gonna buy that. Is it worth a lot more? That’s the debatable question. But with cereals, yes, there’s no doubt now if you take cereals in the UK now, what sets the price? the world market. Whatever we grow in England is tiny compared to America, Canada, and what does Russia want to do; is Russia exporting or is it buying hundreds of thousands of tons? And that makes a huge difference to the overall price. Because the other thing is we’ve gone global. When my uncle was…it was produced in this area, a lot of it would have been consumed…you know, relatively local, I know some went to Newark and Nottingham, but a lot of it would have gone to London. So it didn’t matter if it was corn, vegetables, potatoes, apples, it was consumed relatively locally. Now we’ve gone into a, shall we say a global market, a lot of food is, say traded, I mean you can move food around and it’s imported from all over the world. Whereas years ago you just didn’t have those imports, so when I’m looking at apples these days, I’m going well, you know, I got lovely English apples, but someone saying actually there’s some here from France, are they better, are they cheaper? So as a business, I now, I mean the thing that a lot of people don’t realise these days, a lot of, there is a lot of movement of produce just linked to exchange rate, which never happened years ago. Because if the pound is strong or pound is weak, it makes either importing or exporting…the mathematics is just completely different. So if the market is weak on the continent and the pound is strong, it’ll suck in more fruit or more produce because they’ll get more for it over here even though they’ve gotta ship it here then they will maybe in their own market. So there’s certainly huge amounts of movement of products, doesn’t matter if it’s, you know, fruit or whatever. I mean grain is moved around the world… so is fruit, I mean. I’m in a group…the marketing group we use, World Wide Fruit, is half owned by a group of English growers, and half owned by a group of New Zealand growers. Now that was done so the marketing organisation could deal with the supermarkets, and be able to supply them 12 months of the year. Whereas many years ago Chandler and Dunn would supply apples for the season, and it would then go on to, you know, so it would finish its apples, have a break, and then it would go on to strawberries and gooseberries and various other…

Joe: Does that mean that when the pound is strong, that makes business more difficult for you because you’ve got more presumably cheaper compared to…

P: Well the other thing that they would say is if you talk to an industry guy, if the pound is very strong, trying to export, so it doesn’t matter if you’re making, I don’t know, nuts, belts or cameras or whatever, when the pound is strong trying to export becomes much harder because you’re trying to export in pounds, which then converts to a lot of euros, and people go hm, hm, hm don’t like that! So it does make…and foreign exchange is a big, a lot of people don’t realise what an impact it has on movement between countries or across the world.

R: Do you think it’s a mistake then that we’re not in the euro?

P: I don’t think it’s necessarily a mistake, I was interested in a programme I watched the other day, Robert, where there was a guy that was mainly exporting and he was actually buy…he’s saying at the moment he prefers to buy and he buys a lot of his products in euro, and sell. Cause a lot of it’s…if he’s going to the continent or to Europe, he wants to buy and sell in euros cause then he’s got a, he knows where he is, whereas if he’s buying in…

R: Was that the Virgin Man?

P: No, no, this was guy growing certain food products. He wanted to buy in euros because he could buy at a certain level and he could sell in euro, so he knew exactly where he was, and that his market didn’t get distorted by exchange rates. But he was finding that of course, if you find someone in a lower economy, then a lot of things are based on dollars. So if people are unsure, then they’ll revert to buying and selling in dollars. So it’s…the market’s changed dramatically.

R: Not necessarily for the better in my opinion. … Have you got any questions now, we’ve being kept talking, now I think it’s your turn. L: Could you tell a little bit about how these changes have affected Chandler and Dunn specifically, and how you’ve expanded your farm over the 50 years?

R: Well, by putting up those stores in 1930, where they mortgaged the farm and built these stores, and my father and uncle they waited till, in those days, you know, the whole country was in a depression really. And they waited till they got a good crop of apples and built the store. But, you know, so they built the store between April, or even the beginning of May, and ended only really in September, so…and of course that started us going. Now then because they made quite a bit of money, in 1933, which was only 3 years later, they bought a farm at Perry. That was the start of the increase. And you know, things sort of went on from there, and then of course then the War came and that stopped us, but in 1949 they built another big block of stores, and since then we’ve been building blocks every now and again. You know, once you get a start, once you go over…you can sort of push on, can’t you? Cause you’re making bit of money, and of course you’ve got assets to borrow against. The more assets you got, the bigger you can, the more you can borrow. And you see, and because of the outlets, that’s another thing that I think, because the outlets, sales outlets were done away within a way, little farmers, you know people who had under 50 acres, they’ve all disappeared. If you think of the Parish of Ash now, to when I was… I mean there’s hardly anybody left now. Partly because things like us keep taking them over, I mean, we’ve taken over quite a few, in fact one only a few months ago, that poor little chap. Well, I mean, he wanted to sell it, but…

P: I think what’s happened is…fortunate for the family/the company is that over the years it’s been quite profitable, it has been able to reinvest that money into expansion. And land has become available off and on, over a period of years, and we’ve been able to purchase it, which is kind of expanded over the years, has been able to expand the farm.

R: You see, in 1958 I had 2 brothers and a cousin, and we decided that the company was getting a bid widespread so we decided to branch out a little bit on our own. So we bought a 300 acre farm called Bride farm, and we paid 50 pounds an acre for it, which included a house, and a few buildings, and so the total bill was something like 13,500 I think from memory. And of course we hadn’t got the money, we scratched about, emptied our pockets and we managed to raise about 1500 quid each I would think. So we put that in and then we borrowed the rest from the bank. But you see, when you think that that, only…in fact that seemed quite a lot because previously my father bought some marshland down here, cause this was a marshland farm, he bought some marshland down here for 24 pounds an acre so, in the 1930s, so in 1958 land prices had doubled to 50 pounds an acre. But you see it wasn’t long before people were paying, you know, coming over, people…it quickly went up. I mean 500, 600 and the last lot I bought was 3000 pounds an acre. But having said that, when my wife died, she got a little share in Bride farm, which got 1 eighth share actually cause we had for tax purposes to keep our wives half of our quarter. And when she died, they valued her share, which baring in mind we paid 13,500 for, a 171,000! Which was quite ridiculous because unfortunately you have to pay the tax in money. I mean, you can’t give this tax man a bag of dirt so…extraordinary. I can’t believe it. Now, people are paying huge amounts, much more than 3000; 3 times that.

P: That is the thing with land, you can’t make any more. It’s a finite resource, and it actually, if you look at farming for example, you know, the population’s going up, but the land areas effectively going, or the useable area for farming, is going down. Because you know, you wanting more houses, more roads, more facilities, more schools, et cetera, and that is taking out of the land. So we’re actually, we’ve gotta become more efficient and productive because there’s a bigger population wanting maybe a wider variation and a better quality of food to eat. And if you take it to its extreme now, and it is causing, and we’ve got it in this area, whereas now quite a lot of land is actually going out to food production and going into effectively power production because people are either putting the poorer quality land into solar farms, these ground bound solar farms, or we’ve got two anaerobic digestion plants within ten miles of here, and they’re both running mainly on maize, field crop maize. So they want I don’t know how many thousand acres, this guy that’s running these two things want, so whereas people were growing crops, cereals and whatever, this guy’s come along and said actually, I’ll rent your land for x pound an acre, which is maybe…when the corn prices are particularly high, actually you rent it from me at that cause I can’t earn out of corn, I’d say 200 pound an acre, I think it was at one stage. After net, all your costs, so a lot of it’s now going into effectively power production. So farming has changed from that, from being of course, when you had the horse and cart, of course you had to grow a certain amount, you know, to actually, and your land was used for growing crops to feed your horse. Whereas now it’s changing. Will it change again? I think it’s continually changing.

R: Yes. In answer to your question really, I think the reason we were able to expand is that we were in fruit rather than in, you know, you wouldn’t have done it on pigs or livestock or cereals, not to the same extent, I don’t think. Not to keep…cause we got quite a big family, you know, all in it, you know…I think, you know, if you got a cereal farm, you want about 3000 acres to keep yourself going.

L: And has it always been… So has it been more fruit in the past then now? Because now it’s more mixed farming?

R: Yes, well, see, I’ve done a little bit of family research and I think that the Chandlers started here somewhere at the beginning of the 1700s. But I think the first two generations they were tenants, they rented it. And I think after about 2 generations, I think the 3rd generation managed to buy it. We’ve had it ever since, I mean this is where it started, in this house. It started with about just over 20 acres, or 28 acres or something.

L: And how big is it nowadays?

R: Well, Peter can probably tell you…

P: It’s about 600, just over 600 hectares. There’s 2.47 acres to a hectare. So I’m saying, cause I’m so used to dealing in hectares now because…Yeah, that has, and I think Robert’s right that fruit, it’s an intensive horticultural crop. The costs generally to grow and produce are much higher, but the rewards at the end of it potentially are much better. Many years ago I said, you know with the…. going to local shops and going to the local markets, etc, they used to be able to sell. I mean now, because the demand is for quality, quality, quality, years ago the greener apples all got sold, the smaller apples all got sold, now, we are, the specification has, the bar has gone up, and up, and up and up. And I mean my father told me that Chandler and Dunn used to make its most money when it had its biggest crop. That wouldn’t necessarily fit, that wouldn’t follow now. Because it normally means if I’ve got a big crop, I’ve either gotta go into a lot of promotions or just cause it’s, because it’s a huge, a volume, a big volume crop, it might be too small, it might be too green, it might have too many marks on it, so we’ve got people on the farm now that…we had hail what, 6 weeks ago, we got people thinning apples at the moment, so basically taking off, if you got a tree that’s cropping too much, we’re actually physically taking apples off at the moment. One: to try and make sure that we get the correct size banding, and also if there’s a lot of marked fruit because of hail or russeting or whatever, it won’t make us any money, so there’s no point adding extra cost to it. The worst thing we can do is to pick it, put it into a store and then grade it, for only to go to juice, because that’s giving me a huge negative.

R: The other thing I think is that housewives, now that living standards have gone up, quite rightly, they want the best. They don’t want a smaller apple or a greener apple or one with a mark. It probably doesn’t taste any different, but you know people can afford to buy the best, so now the amount of food wasted is huge really. I mean, it would be more than a third, wouldn’t it? I mean how many apples does old Salvatore take from us?

P: I think it varies hugely from year to year.

R: If you look at the cauliflower field now, they only cut about half of them, do they? The others don’t meet the standard you see. So, because everybody wants top notch stuff cause…I can remember when I was a lad, we…my father brought any strawberries in to tea always the ones that the birds had picked, and everything else, you know, we weren’t allowed to eat the best.

L: Do you think it’s just guided by consumer demand or is there anything else that’s influencing this bar of quality that’s been going up?

P: I think consumer…I think there’s a mixture. Yes, people are prepared to pay for quality, but at the end of the day also the people in the chain have got to make a margin. And if you’re starting off with a low quality product for not a lot of money, then people won’t make money on it, so at the end of the day, the supermarkets still gotta make money out of something, out of the, whatever it sells; it doesn’t matter if it’s a can of beans or a kilo of apples. So I think if you offer someone slightly better quality, quite rightly they’ll go for it. Why shouldn’t they?

R: Yeah exactly.

P: So I think people’s expectations have gone up. There’s no doubt about that.

L: Have there been more governmental regulations and rules affecting quality as well over the years? Or has that remained the same?

P: No, I think that certainly some of the rules and regulations have tightened on you know, we are controlled by minimum size, and the classes have a certain quality issue to them, so they have gone up. But I suppose in many ways, I don’t know many…when you first started, Robert, if there were any kind of rules and regulations on quality or not? So they’ve certainly come in.

R: No, I don’t think so.

P: If I send fruit to a wholesale market now, and it’s, if it’s not up to scratch, I will get a Ministry inspector coming down and having a look and saying, look, this is not up to regulations. So they’ll either send me a report and say you’ve marked it as class 1, we believe it’s class 2, so we’ve down graded it, or they’ll go, this doesn’t meet certain standard requirements, and this has been withdrawn from sale. So yes, so the standards have changed.

L: In how far do you think that has influenced your daily work on the farm? Has it had any impact?

P: On the fruit yes. On potatoes, I suppose yes cause again you’re…people are buy…the thing now, people, you buy with your eye, and then your brain takes over. So if you go and see a lovely apple, you go that looks nice, I’ll buy them. It’s not until you eat that apple and your brain says I either like it or I don’t…Cause if you go into a supermarket the next time, and see that lovely red apple, you go oh, they look nice, and it’s only when your brain says, you know, I tried those and I didn’t like them, that you go I won’t buy them. But if your brain says actually they were quite nice, you buy some more. So it’s a mixture I think. The market is…And there’s a huge amount now done, I mean, the other thing that’s changed dramatically is the amount of money spent on adverts and promotion, I guess.

R: Yes, yes, I think there is. But do you, I mean, you’re quite young really, do you, you see, we used to look forward to seasons, we used to have things in seasons, didn’t you, and you didn’t have them out of season. So it was quite a nice thought to say oh, we can have this now. But now, there is no season cause you can buy strawberries in the middle of a blinking winter can’t you? They’re always available, so are raspberries, so are everything. Everything’s always available. So there’s no longer season. I used to look forward to early potato season, but now…

L: I think you can still

taste the difference between having strawberries when they are in season, and new potatoes as well …

R: Oh you think you still know when they are in season? Yes, of course when they’re widely out of season they very often come from the Southern hemisphere, don’t they?

P: I think what you’ll find there is, of course, yes, I’m glad you could pick up the seasons, but what you gotta bear in mind, cause it’s grown in a different country and in a different type of soil, they naturally have a different type of taste. So yes, it’s good that you’ve got used to a kind of shall we say an English strawberry rather than a…American or Israeli or wherever.

R: But having said that, because the supermarkets require strawberries to, not to go rotten, you know to travel better, the varieties, they do all those things, they look nice, but the trouble is, you can’t eat them in my opinion, they are hard and nasty. The flavour and texture doesn’t seem to matter now you see. When I compare them with the strawberries we used to have, these things they buy when we don’t grow them now, and have to buy the jolly things, well rubbish, they’re absolute rubbish, I wouldn’t give a thank you to some of them.

P: I think of course, the other thing is whereas when we grew strawberries years ago the transport was fairly, you know, went to the local markets very quickly on the day it was picked. Now, because of the way that they’re sold they gotta last, you know, their shelf life has got to be extended. And there’s no doubt that, you know, people wanted them to last longer, but in doing that it’s lost some of, you know, some attributes get lost.

R: You see plant breeders can produce what you want, eventually, can’t they? So I mean if you ask ‘em for those sort of things they do it, but they never think about, in doing it, they, something has to go and very often it’s flavour, and quality and, you know, internal quality. I mean I think the same has happened with apples. Some of the nicer flavoured apples, no longer, you know, we don’t grow them. We used to grow lots of different sorts of apples, but now I mean the number that we grow, because supermarkets don’t like to change varieties, they want to have one variety on the shelf 12 months of the year, don’t they Peter?

P: Well, I wouldn’t say 12, they want longer runs, and there’s no doubt that quite a few years ago, back, you know, the time you’re talking of, the early season variety, there was one variety followed by another, by another, by another. And one variety may have only been there for a couple of weeks then you moved onto another one.

R: Yeah they don’t like that (laughing).

P: And now, I mean that would be another huge difference is that the number of varieties of apple that Chandler and Dunn grow now, compared to what it grew 50 years ago, would be completely different. Because yes, people want more consistency, and even if you go now into a supermarket, you’ll find that they sometimes run certain varieties, such as an early red dessert, because of the relatively short growing season. Cause you can’t breed an apple to grow like crazy and mature, so you get an early season apple, and then effectively stop growing because it’s you know, if you gotta get to grow and get it to mature so it’s ready to eat in, I don’t know, beginning of August, you know, and it blossomed in, you know, maybe April, May time, it’s growth, it’s gotta grow quickly while it’s gonna carry on maturing once you’ve picked it. So it’s shelf life is relatively short. And the way Robert highlighted, wastage, it’s a big issue with supermarkets; they don’t want to put something on their shelf and then find that they’re getting a wastage. Because people aren’t picking them up and buying them. Now, they have behind the scenes some very, very complex systems to monitor their stock and reorder, trying to reflect the buying patterns. Not only of, in between certain days, you’ll find that as you get towards the weekend they order more, because they believe, you know, more people are going to the shops, but some of them will also be looking at the weather forecast, cause they’ll actually alter, say, their orders for strawberries or lettuce or something like that. Because if they think it’s gonna be a hot weekend, they’ll think well, people will maybe eat more salad or fresh fruit whereas if it’s gonna be, you know, cold and really rainy, then they’ll, cause people won’t, or they either won’t go out or they won’t have the barbecue or they won’t have the salad, they’ll have something hot. Behind the scenes there’s a huge amount of work going on, on planning, so that has changed. So I think the marketing, how we grow, the tonnage per hectare, because at the end of the day, we’re a business and we have to make money to survive. So yes, flavour, a lot of people, if you ask them a lot of questions they may put flavour at the top, but when they actually come to buy apples, they’ll go “I like those nice red, crispy, juicy Gala.” They may not be particularly, they may, flavour will still be up as one of their top shall we say requirements, but I think a lot of the younger generation, no disrespect, you want crisp, juicy. I mean we grow a variety here called Jazz, which is a very dense texture, very good apple, it’s got some flavour, but some would say maybe it’s not as flavoured as some of the older varieties. But also, the other thing is, if you pick something too early to try and get it into the food chain, because you know it’s gotta go through so many different things, it’s, you’re picking it in a more immature state. Now we pick apples in a slightly immature state cause I want them to store until February-March time, March-April time. Now, when I put an apple into store, I never actually stop it maturing. All I’m doing is slowing it down. The apple is continually maturing, but if I pick it up, if I pick it too early, then the flavour is not there and it won’t actually…I bought some apricots couple of years ago that had come from … somewhere and I think they’d just been picked too, too early. And yes, they looked lovely apricots, but they did not have any real flavour because they’d been picked immature and they then couldn’t produce their own flavours as they ripened.

L: It’s interesting because in many ways it sounds as though farming has become easier, because of the technology and the machinery, but then it also sounds as though it has become more complicated in many ways?

P: Well, yes, there’s a lot more technology, but at the end of the day we still can’t control the environment, the weather that we’re operating in. So for example, several weeks ago we had a hailstorm. I can’t stop those. Certain years the weather won’t be particularly helpful to pollination, so my crop could be lower. I could have frost. That’s a choice, you know, I chose to be a fruit grower, but we’re not in a manufacturing process where we have control of every element. So we’re, like a lot of businesses, trying to juggle what the consumer wants, and with apples it’s even worse, because I’m trying to guess now, what variety you want to eat in 5 years time, to 5 to 10 years time. So in that respect, it’s got worse because, with all due respect to my uncle, he could sell effectively what he grew. Whereas now, so he, don’t get me wrong, they would go with the varieties they believed because the market, but there’s a very high chance they could sell them all. If I suddenly put in a variety that I think is brilliant, and the supermarkets go don’t like it. I might love it, but is it gonna sell? So I have to now be much more aware of what, I mean we have a trial orchard now here on the farm where we’re getting varieties from all over the world to go what about this one, what about that one. And the chances of actually finding a real winner are very slim. But because an orchard has a 15 to 20 year life, they have to breed it, I trial it for 5 years, and then it’s in. So then I have to order the trees. So, I actually had a meeting the other day with my cousin that runs the farm here, and I shall do the same with Ian that runs Perry farm, to say actually, what are we gonna plant in 3 years time? Because I have to order the trees, the variety of tree. So I’m talking of that, so I’ve then gotta kind of guess what you guys are gonna eat in 5 to 10 years time. Now, with cereals or whatever, it’s, cause it’s an annual crop, and the breed, I’d not say they’re easier to breed, but cereal breeding over the years has done very well and the crops have consistently gone up.

R: Well yeah, but I think it’s true to say that we went through a period when crops…I don’t think in the last 20 years that there’s been much progress really. …

P: They’re not going up in the increment they did. They are getting heavier.

R: No. Within a year or two, you know, we doubled, you see. But nowadays you got just a few, well I think in terms of hundredweights, a few hundredweights an acre. See my grandson down on, he farms down in the South Downs National Park, you know, on this down land and he can grow 5 tons of wheat to the acre on that ground, so he claims, but I don’t know whether that’s true or not, he may be just be boasting, but I don’t know. (laughing, then taking out his envelope with notes and pictures) I got a picture here of the farm staff.

… (Starting to look through pictures, several people talking at the same time)

R: That’s my grandfather, this bloke. Now, I don’t know whether the staff were told it was gonna be a photograph or whether they’re in their working kit. It looks to me as if the ladies have decked out a bit. I mean I don’t know much about it. It was taken on outside here, on the doorstep of this house. Which in those days had espalier pear growing along, I took it off actually when I came here. … That was the farm staff in about 1900, well roughly 1900. I got another one here, which…1903; picking strawberries, and my grandfather and my father are on that, my father was only a lad. … He was born in 1899 my father, so in 1903 he would have been…he’d only been 15 or 16.

P: Have you got one with the combine? And you and Ian, have you got that one?

R: Yes I’ve got that one somewhere. … See here’s another one, which was a presentation to somebody who’d worked for 50 years, where is…that chap, he’ worked here for 50 years, and my father was making a presentation. But that was in 19…1969.

L: 1969, is that taken on the farm as well?

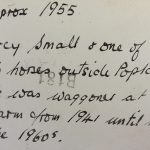

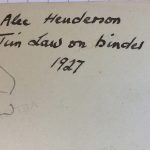

R: He will have taken over in one of the buildings, yes. … (taking out another picture) See, and there’s the first combine we had, and the old army lorry. That’s me sitting on the combine, and I think Ian was just sitting in the lorry cause he wasn’t old enough to drive it. … See we kept the odd horse until about 1955, also there’s a picture of the last one, just outside here. … See and now here is one taken in 1927 that was the very first tractor we had, and that’s pulling a self binder, you see, and it, you can see the sheaves that throws out under the ground. See, a horse used to pull that, it was only a…it was a horse implement and horses pulled it, but you just hooked it on the tractor you see. That was before the days of combines. … See and here’s another, there’s a 1930s photograph of ladies in our pack house.

L: There was a law passed at some point when women couldn’t work on the farm anymore with their children?

R: Well, we, you know, they used to come out in the summertime with children. We didn’t mind the children, you know, they ran about all over the place and they had babies in prams, and they, you know, it all went quite nicely. We never had any, well, we used to be slightly bothered about whether the children would get run over with tractors and things, but they all seemed to get by somehow. But we have to be careful.

P: And now that would be a no no. … Health and Safety.

R: See that’s, that was a later picture of another pack house that’s still in operation that one.

R: There’s another one. You see a chap with a horse thinning broccoli plants.

L: When is that from?

R: in the 1950s. (looking at the back of the picture) Oh no, it’s 71, 72. So we kept a horse to right after… (laughing)

P: I can remember having horses here.

R: Yeah. … Now, there’s a, see tractors went to 4 wheel drive, see this is a 4 wheel drive tractor with a lad driving. …There’s another picture, there’s a combine, the back of combine. … There’s a bailer bailing straw. …Then once you bailed the jolly stuff you see the next thing you had to do was take it away, loading it up. … There’s a picture of me, taken about 1949 on a big American tractor that came over under lend lease. It’s what they called a Rockol tractor, you know, which is running up rows and things, but you see it hadn’t got any cab or anything on it. You just sat up in the open, high up, quite nice really. See these tractors used to run on paraffin, but you started them on petrol, when it warmed up, you switched it over on to paraffin, cause paraffin was cheaper.

L: What has happened to all the old machines?

R: Well, I don’t know, we trade them in, you see. When you buy a new one, you trade it and it goes to the… We got that one because we had an old tractor and it went to Canterbury, and the Germans dropped something on it and finished it off, so then we could get one, because that happened, we were able to get one that, in the war we got a new tractor from America you see, a new one sent in.

P: I think you’ll find, yes, as Robert says, a lot of them were traded in. I’m afraid to say that a lot of it would have been scrapped and reused, whatever. Yes, I mean there are still, I mean the collectives around finding…

R: There’s another one of the combine and the poor people, that must have been me down there trying to clear the bags up in the distance. …

R: See there’s a …an intermediate sort of…this type of tractor was about the 50s and 60s, but the implements you see, the plough is fixed to the tractor whereas you see originally tractors used to pull the plough with a chain, you know, it was loose, but now that was hooked to the tractor, so when it gets to the end the tractor, you know, the man can lift the plough out of the ground, turn round and…But when you had a chain, you had to get off and muck about to turn around.

L: Is that the Ferguson system you referred to…?

R: That’s a Ford. Yeah, but of course all the other manufacturers followed soon, you know. Ferguson invented it, but…you know the others saw it was a good system. And now it’s still used, in all tractors that got what we call a 3-point linkage. You know there are 2 arms at the bottom, and then a top arm you see and it’s the bottom arms that lift the thing up and down, and the top one that sort of stops it from…

P: …pivoting backwards.

R: Yes.

… (taking photos of the photos)…

R: I’ve got a map, a copy of a map drawn in 1757 I think, by the Manor of Goldstone. Would you like to look at that?

L: Is that of the farm?

R: Well yes, it’s sort of, of this area in 1757.

L: I’d love to see that.

R: I’ll go and get it. …

J: So that was the first combine?

P: Yes, that was the, what they called the bagging machine. Can you see the bags over here, there’s one going down there.

J: And that would be your job to pick them up.

(All laughing)

R: Yea, that was the worst part of it.

P: Cause they were…

R: I tried all sorts of systems; I tried to run alongside and get them to throw ‘em off, pull an elevator …

L: Thanks so much.

R: Thank you.

[While driving around the farm, then to the bus stop]

Peter: …1 farm secretary, there’s 1, 2, 3, 4 in the butchery; and so its across the whole business, and the directors, cause we’re all working, there’s 5 working directors. During the middle of summer at peak when we’re picking, we’ll put on another, we have now 24, 34 on now, so were up to 66, and for main apple picking will put another 20, 30 on, so we’ll go up to just under 100. But that’s only for a relatively short period when we’re picking fruit.

Joe: …short term casual labour…

Peter: so that we got 30 odd casuals on now, thinning, they’ll then go into picking plums then picking main crop apple. They’ll take up one extra one to take up corn harvest and then potato…so we’re fluctuating…

Peter: …we’ll just drip water by the roots. The problem with aerial overhead spray irrigation, it just chucks up it in the air and a certain amount evaporates.

Joe: …. you’re wasting water…

Peter: ….so you’re wasting water. So we’re now going more to this, what I call trickle…for fruit…more to trickle irrigation.

Joe: …so is that coming into the ground?

Peter: Basically, we’ve got a system of an underground main to feed a main station, which will then… there’s what we call a header pipe goes underground along all these lines, and we’ll just pump water in to it and it just comes up. So that’s effectively a permanent system.

Joe: Is there a particular crop that this farm would be most proud of? Your piece de résistance?

Peter: I’d like to think fruit, but I’m biased cause I’m on the fruit side. The problem with… something like cereals, whereas fruit is direct to the consumer, I say direct, you actually eat an apple or you eat a strawberry, you don’t go an eat a handful of grain. Someone’s gonna mill it up, and put it into flour to make a loaf…yea, potatoes you do, no, I’d like to think on fruit and we’re reasonably good fruit growers, its stood us the test in time. I wouldn’t say we’re the most progressive, but then, you know, you gotta make money, so it’s a case of just trying to find the balance between… don’t mind his hearing’s not brilliant, so… he’s not doing too badly for 94!

Peter: Fruit growing is, like all things, changing. People are trying different ways of growing things. If you’re right at the forefront, sometimes it works, if it doesn’t it can cost you a fortune!

Peter: we can sell corn what we call forward on the futures market. So basically, I think my cousin has just sold some wheat for delivery in November, for a certain price per ton. But that price is set in stone, and we’ll get that price. If, god forbid we had an absolute hail storm and it wiped us out, we are duty bound to fulfil that contract. Now if the price suddenly shoots up to say twice the price, we’ve gotta fulfil that contract.

Joe: but equally if you produce a huge amount and the global price for wheat is lower, you’ve actually done yourself…

Peter: yes, yes, we’re basically hedging our position. I said to him, if that’s the best price you think you can get at the moment, and you’re happy with it, take it, at least your covering a certain part of your position. Now, it could go up, the thing is, you’ve only got to get a change…even things like the Russian invasion of Ukraine impacted the wheat market, because they suddenly thought “ooh god, what’s going…”, cause, any kind of… something like that, makes people nervous, they get twitchy.

Joe: so, is it yourself, you that negotiates that position? Or a person…

Peter: …on the wheat price? We talk to a buyer, because we’re not big enough to sell in any volume, so we do it though a trader. Same with my fruit I’m not big enough now, whereas Chandler and Dunn used to sell direct to the panellists, I could still do it to a wholesale panellist but they wouldn’t be able to take the volume, to deal with the supermarket I have to bulk my fruit with someone else’s to get the volume to better get into the supermarket.

Joe: which supermarkets do you sell to?

Peter: We actually do Marks and Spencer’s, Waitrose, Morrison’s, a bit to ASDA.

Joe: I may be being really naïve, but Waitrose, Marks and Spencer’s, especially, they sell themselves as being particularly ethical when it comes to dealing with farms…

Peter: yea, those two are what I call top end…M&S, effectively you could say, is very close to being a…it is a supermarket, but, they’re supplying to the top end. Yea, you can go into Marks and Spencer and buy some potatoes ready to cook that have got the mint on them and a certain amount of this, and just stick them in the oven and presto! They’re close to being a deli, in many ways, M&S. The thing that they do, and I know it upsets my uncle, they like to put a name on the pack, its only because they want you as a… this is the cynic in me…they want you to recognize the name, so Peter Chandler, if I put Chandler and Dunn, that’s a corporate kind of nonentity, whereas if you put Peter Chandler on the bag, that’s a person. And every so often they’ll stick a picture of one of me or one of the growers up in a store, and you go, yea actually it’s a person. So you can buy in and relate to it, whereas if I put Chandler and Dunn, you go, well it could be any kind of conglomerate.

Peter: My contract with the marketing organization I deal with, its contract is effectively based on the last delivery it made. There’s no written contract for supply, they can go, “no we don’t want anymore from you tomorrow”, and that’s it, bye. And you think, why do I deal with ‘em? But if I don’t, where do I go?

Louise: Getting back to labour issue we talked about before…not many local people working. Why do you think…

Peter: We get a certain amount. I mean, because the thing is, its casual work so people want…I can fully understand…they either want full time or, they want to know they can work, if you’re a mother with children at school and they’ll want, say actually an ideal part time job will be work from 9 to 3 or whatever, but they want it the whole year round, and of course we can’t offer that. A lot of housewives used to do it years ago, but I think its, you know, they’ve got other part time jobs or…Fruit picking is quite hard, you can earn good money at it, if you’re prepared to put your back into it. But for some peoples….

Joe: …paid per kilo…

Peter: yup , yup …

Peter: Right, I don’t know what the time the next bus is, but they should be reasonably….

Joe: left us in a nice part of the country though, so…

Louise: …and its all sunny, its alright.

Audio

Photos and Documents

Robert & Peter Chandler Interview Archive – Download .pdf version