Finding each other inside a quantum computer

In a paper to appear in the New Journal of Physics (read the accepted manuscriptpublished article here) we tackle using quantum technology a problem we have all faced at some point: how do I find someone who is also looking for me if we cannot communicate? This is called a “rendezvous problem”. The trick is, of course, to have agreed a strategy beforehand. For instance, when we walk with a child into a supermarket we might tell the child “if we get separated, wait for me and I will find you” (thus preventing a situation where we are both looking for the other and missing them or, even worse, we are both staying put indefinitely).

Of course if the child is a teenager who has a mobile phone (and the mobile phone signal is good inside the supermarket – so not the one I go to!) then we just call each other and we guarantee success without the need for a pre-agreed strategy. But there are many real-life situations where communicating is not an option. For instance, two parachutists or drones dropped behind enemy lines may want to find each other ASAP but not be so keen on broadcasting their position to the enemy. Or we may be two robots on opposite sides of a large asteroid, with no communication infrastructure. Those are the kind of situations the “rendezvous problem” refers to.

In those cases, it would seem that we are stuck with the option of agreeing a strategy and hoping that we are lucky and find each other quickly. However, very recently Piotr Mironowicz, of the Technical University of Gdansk, discovered that there is another way: the two parties may share two halves of a quantum object (for instance, two atoms that were originally part of a single molecule) and use what Einstein called “spooky action at a distance” to coordinate their actions after they are separated.

What we have now done, in collaboration with Piotr, is to deduce the exact steps that the two parties would need to follow to achieve this. We then simulated the process inside a quantum processor, which we were kindly provided access to by IBM, and obtained, in the simplest case at least, an excellent agreement between the theory and the experiment.

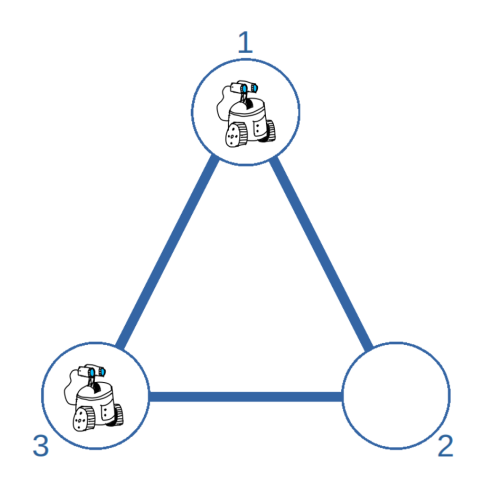

To think of a concrete example (taken from our paper), imagine two robots (let us call them Alice and Bob) that get droppped each on one site, out of three available – see picture. They need to make one move, maximising the chances that they will end up on the same site. Without Quantum Physics, the best Alice and Bob can do is to agree to go to the site with the lowest index. With this plan, they win the game 5 out of 9 times, or 55.6% success rate. This is much better than just using a coin flip, which would have a 33.3% success rate.

Now suppose that Alice and Bob each have a “quantum coin” (usually called a qubit, which is the simplest type of quantum object). Then they can each manipulate their qubit and observe its state (the quantum equivalent of flipping the coin and looking which side it landed on). It turns out that, due to the “spooky” correlations between the two coins (which can have been set up at the earlier time when Alice and Bob agreed the strategy they would follow), this does better than even the best possible strategy: 58.3% success rate. This may seem a small improvement, but we have managed to observe it in our quantum computer experiments and the advantage is predicted to be greater in other, more complex rendezvous scenarios.

It is important to emphasize that Alice and Bob have not told each other which sites they were on – in fact, they have not exchanged any information, other than at the start of the game, before the sites were assigned. However, the two coins have influenced each other and this has introduced correlations between the results of Alice’s and Bob’s coin flips – “spooky action at a distance” indeed!

So what is that “spooky action”, you might wonder? This is the bit of quantum physics that Einstein didn’t like – however, he was wrong, and Aspect, Clauser and Zeilinger shared the Nobel prize in 2022 for carrying out the experiments that proved that. It turns out that when you split a quantum object in half the two halves continue to influence each other even after you have separated them and can no longer communicate. Our work vividly shows some real-world effects of this. The technical term for it is “quantum entanglement”.

This paper is part of Josh Tucker‘s PhD project.

New Journal of Physics

Quantum-assisted Rendezvous on Graphs: Explicit Algorithms and Quantum Computer Simulations

Joshua T. Tucker, Paul Strange, Piotr Mironowicz, and Jorge Quintanilla

Accepted Manuscript online 10 September 2024

Citation: J Tucker et al 2024 New J. Phys. 26 093038

DOI: 10.1088/1367-2630/ad78f8

Abstract: We study quantum advantage in one-step rendezvous games on simple graphs analytically, numerically, and using noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) processors. Our protocols realise the recently discovered [Mironowicz New J Phys 2023] optimal bounds for small cycle graphs and cubic graphs. In the case of cycle graphs, we generalise the protocols to arbitrary graph size. The NISQ processor experiments realise the expected quantum advantage with high accuracy for rendezvous on the complete graph K3. In contrast, for the graph 2K4, formed by two disconnected 4-vertex complete graphs, the performance of the NISQ hardware is sub-classical, consistent with the deeper circuit and known qubit decoherence and gate error rates.

Media dossier

(added 19 November 20246 December 202429 September 2025)

Quantum Zeigeist – Quantum Computers Could Coordinate Moving Devices for Efficient Logistics Say Researchers from University of Kent

KMTV – Kent Research INvestigates Driverless Cars Through Physics