Luvell Anderson: ‘Laughing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Comedic Imagination’

Novelist Paul Beatty wrote, “No matter how heartfelt, white interpretation of Negro humor and Negro existence is often too black.” Comedian Dave Chappelle suggested that part of the reason he left his Comedy Central show The Chappelle Show, was in part due to inappropriate laughter by white audience members. This provokes the following thoughts: Are there cultural artifacts that are too culturally ingrained to even be approached by “outsiders?” If not, what are the conditions that establish a “just right” interpretation in this situation, rather than one that is “too black?” In this talk, I explore these questions by providing a characterization of what Beatty might mean, describe how the diverging development of different linguistic communities gives rise to this, and looking at possible solutions to bridging this hermeneutical gap.

Rebecca Roache: ’45 Minutes of Mind-Blowing Oral Pleasure (Or: A Moderately Engaging 45-Minute Talk About Double Entendre)’

Double entendre, passive aggression, dogwhistles, and sulking all share certain important features:

- they attempt to communicate something covertly, and they do this by

- being ambiguous in that they bear an objectionable interpretation alongside an innocuous interpretation, and

- an important function of the innocuous interpretation is to enable the speaker to deny the objectionable interpretation.

If we pick the right sorts of examples, we can make these behaviours look very similar. Yet, even in very similar cases, our attitude towards these behaviours is very different: double entendre is widely recognised as a comedic device, but the others are not.

Focusing on the social relationships between speaker and audience, I explore the reasons for this discrepancy, and attempt to explain why we tend to find double entendre, funnier than even the most skilful of sulks.

Stuart Hanscomb: ‘Truth and autobiography in stand-up comedy: The genius of Doug Stanhope’

It’s common for stand-up comedians to tell stories as well as, or instead of, jokes. Stories bring something extra to the performance through their aesthetic appeal, and by facilitating alternative forms of humour. Stories presented as true add a further layer of appeal, but most stories told as if true by comedians are not true. A categorizing of forms of comedic story is presented: those that are evidently not true (shaggy dog stories, surreal stories); those told in the third person that are true; those told in the first person as if they are true but are made up or significantly embellished, and those told in the first person as if true and that are largely true.

Some advantages of comedians’ employing first-person stories of this latter kind are discussed, including avoiding disingenuousness or the requirement for audiences to suspend disbelief; the role autobiographical truths can play in challenging audiences’ beliefs and behaviours, and the quality of the delivery. These considerations, along with the question of how we can know if a comedian’s stories are in fact true, will be explored through the role of autobiography in the work of Doug Stanhope. Many aspects of Stanhope’s (highly unusual) life find their way into his act, ranging from his sexual explorations, to his alcoholism, to his girlfriend’s mental disorders and to assisting his mother’s suicide. True stories are also folded into other elements of an act that is highly authentic (there’s little between Stanhope the person and Stanhope the performer); involves spontaneity (including forms of audience interaction), and that often has a ‘point’ (political, ethical). These combine to make a show that is immersive, meaningful and inclusive. At the heart of its excellence, I want to claim, is truth, and links are made with Kierkegaard’s notion of ‘truth as subjectivity’.

Michael Young: ‘Such Shadendenfreude – Unpacking the Televisuality of Humor and Politics in Veep’

In recognition of the topic’s joking terms, this paper will discuss the intersection of humor and politics from a media perspective, particularly through the lens of television aesthetics. It will focus on the genre of political satire in film and television and identifies the popular and critically acclaimed television series Veep (HBO, 2012 – present) as a programme which exemplifies the expression and underlying values of a contemporary strain of aesthetic sensibility – schadenfreude – that runs through its axes of coarse disempowering humor and the perception of power. Specifically, the paper will explore the various aesthetic attributes that contribute to Veep’s affective reception, from its ribald characterization of the corridors of political power in the US to the exacting physical comedy of its lead actress Julia Louis Dreyfuss. Moreover, it will examine how the series’ success results from humorously overlapping some of the more problematic aspects that persists in the political landscape, namely, self-interest, ineptitude and public performance.

As its reflective starting point, this paper begins by first interrogating the significance of humor and politics in film and television. The first section of the paper will briefly trace key historical instantiations of political satire, understood as a genre that humorously sensationalizes the shortcomings, aspirations, dissonances and imbedded social structures of a prevailing political milieu. The second section will then elaborate on the novelty of Veep within this genealogy by highlighting its gendered position as the first comedic fictional television programme of a woman in the White House and then examining the philosophical foundations of the programme’s mode of satire as premised by the concept of schadenfreude and rendered legible by a postfeminist ideology. The third section will then use the close textual analysis of salient and relevant narrative events to show how this satirical modality is useful for making political topics pleasurable, entertaining, or otherwise palatable to viewers whose normative experience of politics is frequently negative. The fourth and final section will consider the ‘real world’ implications of political satire, from the criticism of political corruption and hypocrisy as a social commentary on controversial political perspectives and issues to the potentially dangerous normalization of unstable and insalubrious political personas and viewpoints.

Eric Studt: ‘In the Mood for Comedy’

This talk explores the role that moods play in comedy. Adapting John Morreall’s four principal elements of humour, I argue that the goal of comedy is to produce an enjoyable mood that results in (or at least tends toward) laughter. If the audience does not laugh, the comedian has failed in her task. I develop this point by showing three short clips from the 2018 recording of comedian Hannah Gadsby’s stand-up show, Nanette. As she delivers her routine, Gadsby explains her technique, which boils down to encouraging tension and tension diffusion in audience members. I argue that tension, in this context, is a mood. Of course, tension diffusion is only one technique that a comedian might use for producing an enjoyable mood that results in laughter, so I use Gadsby’s particular technique as an example of successful comedy and not as a paradigm for how all comedy works. I then bring Gadsby’s insights into dialogue with contemporary research on moods in the philosophy of mind by briefly comparing Gadsby’s use of tension with theoretical notions of moods put forward by Peter Goldie, Robert Solomon, Carolyn Price, Amy Kind, and Angela Mendelovici. Finally, I adopt and slightly adjust Jonathan Mitchell’s Mood-Intentionality Thesis in order to clarify how tension, as Gadsby uses it, is a mood and I show that comedy in general depends on a certain kind of comedic mood in order to make audiences laugh. In short, this talk brings the aesthetics of comedy into dialogue with contemporary research on moods and explores how this dialogue is mutually beneficial.

Leyla Osman: ‘Penetrating Seriousness: The Joker in Stella Dallas’

In this paper I will discuss the role of an archetype known as the ‘joker’, ‘trickster’ or even the ‘fool’. To bring this role into focus I will look at Ed Munn’s role in the film Stella Dallas (1937), as he represents this joker persona. A joker is someone who is capable of mocking what society holds dear; he laughs at any display of seriousness. Most often, society avoids such people, but at same time there is the desire to have them around. If there is no one to make fun of society’s actions, then the society risks becoming a parody of itself. In such a state, the society becomes an ice sculpture we must tiptoe around. The role of the joker becomes crucial at this stage, as he is the only one capable of breaking this sculpture. He does not obey the rules and he does not shy away from making fun of the seriousness we attend to.

Dieter Declerq: ‘Satire as Coping with a Depressing Socio-Political World’

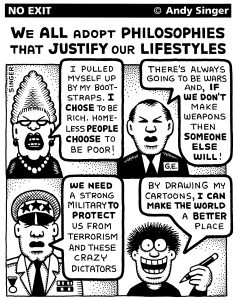

Figure 1.

Many satirists develop comic strategies to cope with a depressing socio-political world. Consider Fig.1, in which Andy Singer uses what I call ‘ironic characters’ to both ridicule political adversaries and cope with the limited efficacy of his political critique. Ironic characters are a ploy in the ironic communication of satirists, who let them assert viewpoints in a fictional world which are deficient positions about real-world affairs. Interestingly, Singer does not only direct his irony at hard-line conservatives, but also at himself – or, rather, a version of himself that believes his cartoons will emancipate the world. This reflexive use of irony is not only designed to be funny, but serves as a strategy to cope with the limits of political critique.

Robinson has argued that “formal or structural devices in literature [can] play the role of coping mechanisms” because they serve to reappraise content that is initially appraised as emotionally challenging” (2004, 196). My argument is that formal structures like ironic characters have particular innate potential to serve as coping strategies, because they are humorous. In this respect, Carroll has developed an incongruity theory of humour, according to which humour results from “an anomaly (…) relative to some framework governing the ways in which we think the world is or should be” (2014, 17). Carroll specifies that “in order for humorous amusement to obtain” one “must regard the incongruity not as a source of anxiety but rather as an opportunity to relish its absurdity” (2014, 29). For this reason, “what is potentially threatening, frightening, or anxiety producing about [humorous incongruities] must be deflected and/or marginalized” (Carroll 2014, 30). This phenomenon, which Carroll characterises as “humorous distance or humorous anaesthesia”, serves as a clear framework to investigate how humorous strategies in satire, like ironic characters, serve as coping devices (2014, 32).

Matt Hargrave: ‘‘Putting yourself out there’: Depression in contemporary stand-up comedy and its relationship to a politics of self’

This paper considers depression as a material component in an artistic process, rather than psychological injury or social stigma. Drawing on interviews with UK based comedians who utilise material about depression in their work (Hal Branson; Susan Calman; Seymour Mace; John Scott; Felicity Ward) and participatory stand-up training run with and for people who use mental health services, the paper analyses stand-up comedy’s potential to intervene in debates about depression, vulnerability and the politics of self.

Several questions drive this enquiry: How does treating depression as a joke – as material alongside other subjects – redefine the terms of engagement with it? Which competing discourses define depression and how can stand-up contribute to them? And to what extent does stand-up undermine or perpetuate normative tropes of public disclosure or recovery?

The paper engages with two main currents of philosophical enquiry: First, it follows Alain Ehrenberg’s assertion that depression is an endemic contemporary phenomenon; one which reflects the weariness of the postmodern subject, who must undertake the daily labour of self-definition (The weariness of the self, 2016). The paper argues that stand-up is a particular kind of self-definitional labour, one that reflects what it means to live in a world of perpetual, self-monitoring, choice. Second, it asserts that psychological vulnerability is an increasingly urgent question in the neoliberal era, in which the prevailing mode of selfhood is ‘entrepreneurial subjectivity’; which promotes competitive self-seeking as the only rational choice (Erin Gilson, The ethics of vulnerability, 2013). The paper argues that stand-up, as an artistic and social platform, offers a unique place to observe vulnerability at work. By extension, the paper explores how ‘therapeutic subjectivity’ – the existence of an inner self that needs to be witnessed and understood – is emblematic of a culture which makes the individual consumer solely responsible for his or her own health.

Tom Baker: ‘Comedy, Empathy and Relatability’

In this paper, I explore the varieties of empathetic and sympathetic responses we have to comedy and how these responses interact with the comedic and educative features of stand-up. It is commonly believed that in order for a stand-up comedian to be successful (read: captivating, funny, etc.) they must be at least minimally relatable to their audience: no one wants to hear about the first-world, champagne problems of rich, famous, beautiful people.

Thus, though there are exceptions, comedians must maintain a sense of everyday-ness about them. This relatability allows the audience to more easily empathise with the comedian’s perspective; to more easily imaginatively adopt their cognitive and emotional states (Coplan 2008). To use the shoe-wearing metaphor for empathy: the audience imaginatively place themselves in the comedian’s shoes (or at least the shoes they perceive them to wear). In this way, comedians can encourage their audience to laugh with them. A different type of response, which is used to great effect by comedians such as Sarah Silverman, is what Giovannelli (2009) calls proxy sympathy: the sympathetic response to someone based on an assessment of the situation she is in, which is contrary to her own assessment of the situation; a ‘if she only knew’ form of sympathy. By presenting themselves as oblivious to certain conventions, facts, etc. comedians can encourage their audience to respond in this way and effectively laugh at them. Finally, I discuss how each of these approaches can result in enlightening comedic moments by creating communion among the audience members, along with or separate from the comedian.

Toam Semel: ‘It’s Funny Because It’s True: The Everyday Comic Event as a Work of Art’

We often marvel at a humorous remark’s ability to unmask, unveil or shed light on its subject; however, this affinity between the comic and truth is hardly ever explored by philosophers. This paper will attempt to flesh out the relationship between the comic and truth, by suggesting a novel way of analyzing the comic event, in hopes of arriving at a deeper, richer understanding of the comic phenomenon than the one reached by traditional approaches such as incongruity, superiority or relief theories, as well as aesthetic accounts. I propose to analyze the comic event using the conceptual framework set forth by Martin Heidegger in The Origin of the Work of Art, where he refers to the work of art as ‘a happening of truth’. I will draw on his conceptual scheme and show how the characteristics identified in the artwork can be found in the quotidian comic event – a spontaneous humorous remark, a haphazard amusing sighting – which will be my main focus. Ultimately, I will show that the quotidian comic event can be viewed as a proper work of art in Heideggerian terms, one which we create and take part in, in our day-to-day lives.

Considering the comic event as a quotidian work of art provides a new understanding of its peculiar status in our daily lives, its meaning and its intricate mechanism. This traditional talk will examine everyday examples, and demonstrate how this conceptual scheme addresses many facets often overlooked by other approaches – namely the importance of context; the audience’s role; the meaningful involvement the comic work entails in place of disinterested detachment (aesthetic approaches) or objective rationality (incongruity theory); and most of all its nature as an instance of truth, where disclosure and concealment are forever intertwined.

Matthieu Chauffray: ‘Humour and philosophy: is that a joke?’

Humour is a language tool, and as any other tool, its value depends on what is done with it. Indeed, humour can be either a formidable social lubricant or a terrible weapon.

Traditionally, philosophers analyse humour according to 3 theories :

- superiority theory : we use jokes to dominate others. Thomas Hobbes (Leviathan, I, 6) argued that a joke is a sign of “sudden glory” : when I detect someone else’s weakness, I make it obvious to others so they are distracted and do not see my own failures.

- relief theory : jokes are a balm for our wounds. Sigmund Freud (Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious) notes that humour allows one to rest. In doing jokes, one retreats from one’s inescapable distresses and thoughts of death. It also makes one able to take care of others by making them laugh.

- incongruity theory : jokes are a language disposition. As Homer in the Iliad or Shakespeare in Hamlet, the joker has the ability to connect words, images and concepts that are inadequate. In doing so, she surprises us (as Aristotle would say in his Rhetoric, III). Humour is then an intellectual virtue shared by writers, rhetoricians and comedians

If humour is an intellectual virtue, can we say that it is also a moral one ? If so, what would this mean exactly? This is the fundamental challenge of the proposed presentation: humour is the best understood as seen as a disposition of a person, conform to a series of intellectual and moral criteria.

In order to grasp these criteria, I will attempt to answer three specific questions:

- How can jokes create divisions between people ?

- How can jokes function as a relief ?

- How can jokes be made at all ? (in an intellectual and moral sense)

Alan Roberts: ‘Humour is a Funny Thing’

Humour is a funny thing – everyone knows it but no-one knows what it is. Consulting a dictionary on the question ‘What is humour?’ only reveals an uninformative circle of definitions that cycles between ‘humour’, ‘amusement’ and ‘funny’.

The Oxford English Dictionary provides a typical example:

humour (n.) The quality of being amusing or comic, especially as expressed in

literature or speech.

amusement (n.) The state or experience of finding something funny.

funny (a.) Causing laughter or amusement; humorous.

This circle of definitions reflects the common usage of the words ‘humour’, ‘amusement’ and ‘funny’ in everyday speech. Indeed, people often speak as though humour, amusement and funniness are roughly the same thing.

However, I argue that humour, amusement and funniness are three closely-related but distinct concepts. The dictionary’s uninformative circle of definitions must be untangled into an informative sequence of definitions in order to avoid being tied in conceptual knots. In this presentation, I do that untangling and produce the following sequence of definitions:

Amusement: Subject S is amused by object O if and only if O elicits from S both the

cognitive and affective components of amusement.

Funniness: Object O is funny if and only if O merits amusement.

Humour: Object O is humour if and only if O is intended to elicit amusement.

In order for this sequence of definitions to be truly substantial, definitions must also be given of the cognitive and affective components of amusement (e.g. superiority theory, incongruity theory, release theory, play theory). Though, nonetheless, this sequence of definitions provides a conflation-free foundation on which to build a theory of humour.

Mary-Ann Cassar: ‘Unpacking the Notion of Incongruity in the Analysis of Laughter-Provocation’

Most theorists of humour would agree that the perception of an incongruity is a crucial ingredient for the triggering of laughter, indeed a necessary factor. Noel Carroll in his provisional theory of humour lists as a first requirement for humans to be in a state of comic amusement that ‘the object of one’s mental state is a perceived incongruity’. His theory is ‘provisional’ as he acknowledges that there is some justice to the objection that ‘incongruity is too vague a concept to be of much use’.

In this paper I shall attempt to clarify the concept of ‘incongruity’ in the context of laughter-provocation. Starting from Aristotle’s position in Poetics 5 that ‘the laughable arises from an ugly, but neither traumatic nor lethal, misfiring’ as the focal instance that unifies all the other instances of laughter-provocation, I shall attempt to show how the concept of ‘misfiring’ may be replaced by that of ‘fallacy’, covering both formal and informal fallacies, and how these different types of erroneous reasoning underlie the ‘perceived incongruity’ in any type of laughter-provocation. I shall use Maurice Finocchiaro’s taxonomy of fallacies with some minor adjustments to identify the different types of erroneous reasoning and also show how these feature in literary texts to produce laughter-provocation in the works of authors such as Homer, Dante, Shakespeare and Freud.

Kate Lawton: ‘What Do You Think You’re Laughing At?: Laughter as an indicator of categorical boundary transgression in constructing identities’

I will explore the idea that laughter is triggered by the transgression of conventional categorical boundaries.

It is helpful to refer to the work of philosophers such as Freud and Bergson to introduce the idea of categorical boundaries, and laughter as the way in which we indicate to others – and also to ourselves – that we recognise their transgression for what it is. If someone slips on a banana skin, do we laugh in order to indicate that we would not do so ourselves? Comedy can form a frame of reference in its own right: ‘It is an ex-parrot’, for instance. The benefit of this semi-private language is the ability to identify ourselves as part of an ‘in’ group.

We also laugh alone. Encountering something that makes us laugh when there is no one around suggests that laughter also reinforces personal identities. We strengthen our impression of ourselves through our choice of humour. We laugh at things alone which we would not laugh at in company, and vice versa. Laughter is a public and a personal phenomenon, and performs an identity-forming function in each case.

I have for three years written sketch comedy for the BBC, and worked with the BBC New Comedy Show to encourage new writers. I am also currently studying for a PhD in philosophy at UEA. My thesis aims to understand historical thought using philosophy of history and philosophy of mind, and examine the possibility of historical knowledge about past emotional experiences.

I propose a discussion workshop shaped by a series of questions, and ideas from the group as they explore this topic. It may be useful to incorporate video clips to demonstrate the use of categorical transgression in comedy.

I would be very happy to be involved in a panel in conversation led by a philosopher.

Identifying the basis of the ‘perceived incongruity’ would hopefully contribute to making the notion less ‘slippery’ and more useful “in isolating […] the recurring variables in the leading structures of humour” in answer to Carroll’s call. Knowing the recurring variables in the leading structures of humour would certainly come in useful to theorists and practitioners alike.

Sully O’Sullivan: ‘The Ethics of Offensive Comedy: Punching Up, Down and Sideways’

The presentation will use a series of real world examples faced by stand-up comedians dealing with the issue of offence, and show how different ethical systems will yield contrasting moral judgements of their actions.

The presentation will then use relevantly adapted versions of the famous ‘Trolley Problem’ thought experiment to analyse our moral instincts concerning comedic offence.

The presentation draws the following conclusions:

- Offence is undesirable even when it is necessary collateral damage in the obtainment of a higher good.

- How we define the art form of stand-up comedy directly impacts how different ethical systems treat comedic offence.

- The moral obligations of the comedian and the audience, when it comes to the subject of offence, are not equal.

- The study of the ethics of offence in stand-up comedy.

Rebecca Davnall: ‘Doing Hate With Jokes’

We generally accept that jokes grounded in stereotypes about marginalised groups are disrespectful, but in what way? In this paper, I argue that such jokes operate similarly to archetypal uses of slurs; they update what David Lewis called the ‘conversational score’, by making use of historical oppressions to raise the status of some participants in an exchange and lower that of others. So just as a white person who utters an anti-black slur makes a grab for social capital by leveraging the fact that white people enslaved (and continue to oppress) black people, a white person telling a joke about a stereotype of black people uses laughter to leverage their continuing marginalisation.

A slur succeeds in updating the conversational score if its utterance is not contested by other participants in the situation. Changes to the conversational score are not merely unpleasant, they can have lasting consequences, including long-term, cumulative psychological harm as well as marking people as targets for violence. With jokes, however, the success condition is not merely assent (or silence), but laughter, because jokes designate their objects as appropriate targets for mirth. This means that jokes can take advantage of the social dynamics of laughter – laughter is not always voluntary, is often a non-cognitive response, is self-reinforcing and infectious – to secure changes in social status. These changes mark populations as ridiculous (as appropriate targets for ridicule i.e. laughter), which is unambiguously disrespectful. Thus, jokes are potentially a potent vector for hatred and marginalisation.

Michela Bariselli: ‘How to harm with humour: the harm of derogatory joking’

Humour is often used in a derogatory way, to offend, disparage or diminish. The Incongruity Theory of Humour claims that a necessary condition for comic amusement is the perception of an incongruity. This definition describes the object of amusement, but it leaves unexplained the fact that often humour is used in a derogatory way. Furthermore, when incongruity theorists address the morally dubious side of humour, they focus on instances of humour that employ derogatory stereotypes, and to which these instances appear to owe their badness1. However, humour can be used in a derogatory way without employing any derogatory stereotype.

This paper aims to fill the gap left by the Incongruity Theory and to provide an account of derogatory joking that is compatible with this theory. To fill the gap left by the Incongruity Theory, I discuss instances of humour as speech acts, and consider examples of derogatory illocutionary acts (i.e. acts done in speaking). For example, in using humour for derogatory purposes (‘making fun’) one might be performing the illocutionary act of ranking: by emphasising a deviation from a certain norm (incongruity), one ranks the butt of humour low on the scale of values associated with the norm disrupted. This understanding of the use of humour allows me to highlight a new type of harmful speech, derogatory joking.

Zoe Walker: ‘The Joke’s on You: Harmful Jokes and Moral Responsibility’

Sometimes jokes cause harm. When this happens, it is natural to consider whether those party to the joke should be held responsible in any way. Should we blame someone for telling a joke that hurts others? Should we blame hearers for enjoying the joke? I would like to propose a presentation on these questions concerning the relationship between moral responsibility and jokes, for a traditional workshop format.

I will start by offering a few examples of ways in which jokes can cause harm. I am particularly interested in what I will term ‘oppressive jokes’: jokes which can contribute to forms of oppression such as racism, sexism and homophobia. I take it that at a minimum, such jokes can make light of oppression in a way that obscures its seriousness. At worst, they may actually negatively change the beliefs and attitudes of hearers concerning the oppressed group in question.

My main project will be to explore the moral responsibility of joke tellers. Is a comedian’s responsibility solely to amuse? This seems naïve, but then what responsibility do they have to ensure that their jokes have no ill effects? I will answer these questions by discussing the intentions of the joke teller, reasonable expectations of audience uptake of these intentions, and how this is complicated by difficulties with satire and identifying the butt of a joke.

Finally, I will say a little about the moral responsibility of hearers. It is often thought that amusement is involuntary, and thus that those amused are not responsible for it. I would like to question both parts of this claim, drawing parallels with implicit bias and arguing that hearers ought to be held responsible for even involuntary complicity in oppressive jokes – though to a lesser extent than joke tellers.

Daniel Abrahams: ‘Winning Over the Audience: Trust and Humour’

In this paper I advance a novel way of understanding humour. I propose that the relationship between the humourist and her audience is understood by way of trust, where the humourist requires the trust of her audience for her humour to succeed. The humourist may hold (or fail to hold) the trust of the audience in two domains. She may be trusted as to the form of the humour, such as whether or not she is joking. She may also be trusted as to the content of the joke. Examples of this include what the point of a joke is, or its target; this is the question of who is being laughed with or laughed at.

This approach has two distinct virtues. The first is that it makes sense of partial successes. These are cases where the humour neither completely succeeds nor fails because the audience does not fully trust the humourist. The second is that it explains intuitions about ethically dubious humour and why certain classes of humour, especially those dealing in racialized and gendered identities, are more readily (but not necessarily) accepted from humourists of those identities.

The paper will have three sections. In the first section I establish how I will talk about humour. I present a social account of humour which understands humour as an interaction between humourist and audience, with the goal of the humourist standardly (but not necessarily) being the get the audience to laugh. In the second section I show how the standard account of trust maps on to the social account of humour, with both the reliance and reflexivity conditions of trust being met. In the third section I show how understanding humour through trust helps us understand ethically dubious humour.

Poppy Collier: ‘Audience and Ordeal’

I will explore the performance of stand-up comedy to an audience as an ordeal, using the concept of aesthetic risk. When talking about risk, we have to ask, what is at stake? I will present my experience as a performance artist (wearing bedsheets and singing into vacuum cleaners) against my experience as a stand-up comic (talking about being in love with an extractor fan) to explore the different risks, different tensions within each practice.

I will draw upon the concept of initiation and ordeal within Deleuzian philosophy as presented by Joshua Ramey and ask what the comedian is initiating themselves into. This will inevitably lead us to paddle in Freudian waters and will allow us to compare comedy performance to the earliest instances of lived experience: the inter-play between parent and baby as entertainer and audience, and the subtle change that occurs when the child becomes the entertainer and the parent the audience. Does the ordeal of performing funnyness free us from Oedipal fears of castration by transforming us into bodies without organs? And is the comedy audience a many headed, demanding, judgmental baby? If the parent and baby relationship is one of power balances, and the opposite of control is surrender, then I will posit that the concept of tension within a stand up performance, most eloquently described by Hannah Gadsby in Nanette, requires a comedian to oscillate between the two.

I will conclude by exploring the idea that performance is an attempt to create an-end all within a be- all: creating a finality around a lived moment so that it can exist outside of time. If we accept that a comedian’s persona is an exaggerated aspect of self, then is the stand-up comic’s ordeal thus one of killing an aspect of oneself in order to always preserve it? (And, seeing as we’ve gone through initiation, when do we get to start a cult?)

Ethan Nowak: ‘Humor, personal style, and self-cultivation’

Although the ‘big’ moral moments of our lives have traditionally attracted the most discussion, philosophers have sometimes called for attention to be paid to the significance of ‘littler’ moments as well. According to Confucian thought, for example, the truly remarkable moral qualities of the sage cannot be appreciated by asking what she would do if she came across a drowning child—after all, (essentially) everyone knows what to do with drowning children. Instead of moments of crisis, Confucius holds, the fullest expression of the sage’s moral character can be found in everyday life, where the range of plausible answers to the question of how we should proceed is essentially open-ended.

On the Confucian way of thinking, elements of which have resonated recently in moral philosophy and in aesthetics, the ever-changing circumstances of our daily lives constitute both a special challenge and a special opportunity. Since the multitude of choices we face every day about how to behave defy codification, responding appropriately to them requires our constant attention and reflection. For the same reason, those choices offer us the chance to express our moral sensibilities with a particularly high degree of resolution, and thus, to develop ourselves in distinctive ways as moral agents.

In this paper, I argue that similar considerations can be used to reveal the fundamental role humor plays in allowing us to cultivate our personalities and to structure our interpersonal relationships. The perpetual novelty and the tremendous variety of features of contexts and conversations that can be made targets of irony, wordplay, and other sorts of comic attention make humor into an especially fine-grained vehicle for displaying our intellectual and aesthetic sensibilities, and for engaging the sensibilities of those around us.

Chris Kehoe: ‘Just for laughs: A lawyer’s guide to comedy’

Two things are said to me more than any other – 1.”How do you defend someone who you know is guilty?” And 2. “Tell us a joke then.” Such is the lot of the barrister cum stand-up comedian. A third common refrain when people hear that I am a barrister by day and stand-up by night is, “That’s quite a difference.” But is it? Increasingly I think not.

Law can be defined at its most basic level as a system of rules, created and enforced through social or governmental institutions to regulate behaviour. In other words it is a means to systemic order. Comedy on the other hand is the subversion of order. Both require shared understanding of rules and social norms. Comedy allows us to poke fun at those rules; to say things we would or could not, and to explore the boundaries of acceptable behaviour in a relatively safe manner.

A functioning society requires both law and comedy. It needs regulators and clowns to keep each other in check. I will look at the mechanics of legal and comedic practise to outline the similarities between the two, from the linguistic dexterity vital to each, to the ribaldry of the robing and green room. Ultimately I will seek to show that comedy allows us to be tourists in an anarchic land in which really we would never wish to live.

Nicole Graham: ‘Laughing Gurus: Finding Meaning Through Jokes and Humour’

The pervasiveness of laughter in our lives often means there is an assumption of our innate understanding of it; as a result, its importance is often overlooked. However, this paper will argue that jokes, humour and laughter can play a central role in religious and spiritual experience and is a tool by which we might find meaning in our lives.

In general terms, laughter has historically been treated with suspicion by more ‘traditional’ religions of the West, and the association of jokes and humour with key religious figures has been actively discouraged. Instead the cultivation of a serious attitude and approach to life has been deemed more appropriate (see for example Morreall 1989, Gilhus 1997, and Schweizer 2017). In the East, there has been a greater openness to considering laughter as means of religious experience (see for example Hyers 2004) and humorous anecdotes are frequently used as a pedagogical tool. Indeed, the charismatic leader and self-proclaimed spiritual guru/mystic, Osho Rajneesh, declared that “life is a cosmic joke” (Rajneesh 1998, 77) and he sought to place laughter (and humour) at the centre of his spiritual philosophy.

I will argue that humorous anecdotes and jokes can play an important role in highlighting meaning in our lives, and that they have been used by various religious traditions throughout history to do just this. Thus, this paper will explore how laughter can be a contributing factor to religious experience and offer a deeper understanding of life.

John Ryan: ‘“Make them laugh, Make them listen”. A talk on the power of comedy.’

I believe that if ‘You make them laugh, You make them listen’ and use my humour to successfully raise awareness of health and social issues. It’s an effective social tool. A Babies proximity seeking smile encourages bonding. The Child grins and everyone gets overcome with emotion and smiles back. A feeling of warmth develops, and the infant learns the power of spreading joy. Smiling and laughter are universal behaviours, they lubricate social and working environments. For some of us, we realise that we not only have the ability to physically cause this reaction but also learn to put words together that start the process of group bonding via laughter. We are often the awkward person on the edge of the group noticing the nuances and idiosyncratic behaviours in others. We highlight these to create ideas, theories and characters that entertain and make us attractive to people. I worked in Community care for ten years and humour very often helped clients through dark times. I was always the office joker cracking gags and lightening the mood. Thus, Stand-up comedy became a natural progression for me and I now travel the world performing. We comedians, like philosophers ask “Why”, we challenge convention, we prick the pomposity of stuffiness and we mock authority. Our non-conventional thinking makes us ideally placed to operate outside the comfort of the comedy circuit. So, I use my comedic skills and work experience in projects around Men’s health, Student engagement, Ptsd and Mental wellbeing. The Laughter indicates it is funny and the feedback suggests it is effective. My humour draws them in, my words get them thinking and the interaction gets them talking. It is a powerful and successful way to destigmatise, raise awareness, challenge stereotypes and ultimately get people talking. They laugh, they Listen, they learn.

Charlie Duncan Saffrey: ‘The Stand-up Comedy Club as Philosophical Environment: How ‘Stand-up Philosophy’ has succeeded where Academia hasn’t’

Much has been written about jokes, and recently a handful of researchers have turned to phenomenology as a way to research the more specific philosophy of stand-up comedy. There is now also an extremely broad range of ventures into ‘popular philosophy’ (often used as a catch-all term for philosophy books, podcasts etc. in which philosophy can be found outside of academia).

However, little has been said about the specific potential of the stand-up comedy club as a place where philosophy itself might effectively be done. This paper will argue that the phenomenology of the comedy club itself lends itself to a public philosophy which is both imminent, fun, and of a higher dialectical quality than some might expect.

Three brief and interlocking arguments will be made. The first will borrow from the author’s work on the necessary and sufficient conditions of what ‘stand-up comedy’ is, which itself derives from an amended version of the conditions set out by Double (2005) on the definition of stand-up comedy. The second will adapt an argument from Cooper’s A Philosophy of Gardens (2006) which emphasises the uniquely gestalt phenomenology of gardens as a place of reflection, created out of more than the mere plants within it; parallels will be drawn with the environment of the comedy club as a place for critical dialectical exchange between performer/audience. The third will draw on the author’s own experience of founding a successful live comedy/philosophy event where philosophical arguments are critiqued and debated, to show that the educated general public are capable of participating in, and benefitting from, good philosophical dialectics in a way that ‘pure’ academic philosophy has not always understood.