This practice-as-research workshop gave me the opportunity to explore violence as it is brought to life on the early modern commercial stage. Using extracts from Thomas Middleton’s The Revenger’s Tragedy, The Lady’s Tragedy, and A Yorkshire Tragedy, and John Ford’s ’Tis Pity She’s a Whore, the actors, audience, and I examined the relationship between words and actions on stage, focusing particular attention on stage directions and deictic words as the descriptors of and impetus for movement. By putting a series of five scenes on their feet, we considered the intersections between rhetoric and performance, and investigated some of the ways in which language can inform staging.

My goal in this workshop was to create a collaborative environment where everyone felt comfortable asking questions and offering possibilities for staging. This included not only the actors but the audience. It was really important to me to get as much input as possible, particularly from those who didn’t have much experience with these plays. I asked the actors and audience to speak up if they heard cue words that we hadn’t utilized, if they thought the text called for a different kind of movement, or if anything was unclear.

For the purposes of this workshop, I removed all editorial and authorial stage directions from the actors’ scripts, so that we could pinpoint those moments when the text itself called for action. Some of this was through implicit stage directions in the dialogue, some through contextual information from other characters. There were places when the actors hadn’t consciously picked up on a textual clue, but acted or moved on some sort of gut instinct. These instinct-driven movements were perhaps the most helpful, when I could stop the scene and say “why did you move on that word or line? What prompted that response?” Often times it was because they were listening (quite intently) to the other actors; even when their character wasn’t directed to speak, there were still opportunities to react to another character’s words.

The first scene, from Middleton’s The Revenger’s Tragedy (1606), offered more opportunity for discussion than I expected. I chose this scene (2.1.10-47) as a gentle entry into the workshop mindset: Vindice in disguise as Piato propositions Castiza on behalf of the Duke’s son. She slaps him and exits, and Vindice expresses his delight at her steadfast chastity. I figured that this scene was relatively straightforward, with little opportunity for alternative readings, but we ended up spending at least 20 minutes discussing what kind of physical chastisement this was (a slap? A box of the ears or nose?), how many incidents of contact there were (is this a single slap or a one-two combination?), and where the contact should happen. We tried a variety of options, from having Castiza slap or punch Vindice before or after her line “[r]eceive that” (2.1.13), to adding an additional movement a few lines later when she says “I’ll reward thee for’t” (2.1.19), and exploring where exactly Vindice gets hit (playing on the ambiguity of his lines: “It is the sweetest box that e’er my nose came nigh, / […] I’ll love this blow for ever, and this cheek” [2.1.23, 25, emphasis added]).

Vindice is slapped by Castiza.

After exploring cue words in Revenger’s, we moved to two scenes from The Lady’s Tragedy (1611), where I was most interested in examining how language informs relationships and creates obstacles. In Act 3, scene 1, I chose to focus on Sophonirus’ death rather than the eponymous Lady’s, and how he transitions from being a threat to speaking about a threat as he dies. This was manifested in the actors’ use of props: by the time Sophonirus says “Well, you have killed me, sir, and there’s an end” (3.1.32), the actors determined that he should no longer be holding his sword. Somehow, in the scuffle with Govianus, Sophonirus must lose his dagger (a prop we decided he needed based on Govianus’ line “[f]all to, and spare not” [3.1.29]). Combined with the actor falling to the ground as if he had been stabbed, the loss of the prop dagger made it visually clear that Sophonirus could no longer be a danger to the Lady. This was a great reminder of the intersectionality of language and performance: we needed both aural and visual signals for the scene to appear coherent. Imagine the sense of disconnect an audience would feel if Sophonirus were to stand around, holding his dagger loosely and looking bored, while saying “Well, you have killed me, sir” (3.1.32) or “She cannot ‘scape, / No more than I from death” (3.1.38-39)! To state the obvious, the dialogue acts as an impetus for actions that make sense within the context of the scene.

Govianus and Sophonirus fight.

This was an idea we continued to build on in Act 5, scene 2 of The Lady’s Tragedy. This scene hinges on the understanding of words guiding action, making full use of deictic words and directional phrases. The scene begins with an exchange between the Tyrant and Govianus:

TYRANT Look on yon face and tell me what it wants.

GOVIANUS Which? That, sir?

TYRANT That. What wants it? (5.2.66-67)

“That” face is the Lady’s, who, although dead, is very much the subject of this scene and the stage object on which both men focus their attention. Every action the two male characters perform in this scene revolves around the Lady’s body, even when speaking about their own bodies. For instance, when Govianus says in an aside that a “religious trembling shakes [him] by the hand” (5.2.81), he is describing the effect of his interaction with his fiance’s corpse. The Tyrant likewise says that his “arms and lips / Shall labour life into her” (5.2.108-109), as he embraces the corpse. While working on this really tactile passage, I was delighted that the actors were finding possibilities for some dark humor — after the Lady’s body has been done up with poisoned cosmetics, the Tyrant orders someone (Govianus, perhaps, or a servant) to “keep her up, / I’ll have her swoon no more” (5.2.105-106), indicating that the body has fallen over in its chair. The actor playing the corpse took this directional phrase very seriously and the slumping corpse caused a number of those watching to… well, corpse. We ran this scene in parts and as a whole quite a few times, exploring different avenues for physical reactions and relationships between the characters. Where should the actor playing Govianus stand to watch the Tyrant die of poison? How much and in what ways should each character interact with the dead body?

Govianus and the Tyrant center their attention on the Lady’s corpse.

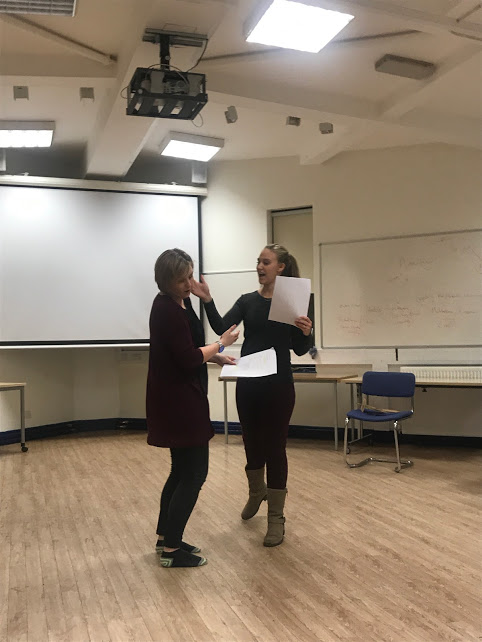

The fourth scene I chose, from A Yorkshire Tragedy (1605-1608), allowed us to consider similar spatial and physical questions. This scene (5.15-55) worked least well on its feet — all because in my effort to not push the actors to make specific movements in certain places and instead let them make organic choices, I didn’t give enough contextual information on the play and how this scene fits into the whole piece. As rough as that made things, I found this portion of the workshop was actually the most helpful. I have been writing about Yorkshire Tragedy for a number of months, digging into the grammar of performance, and this workshop gave me the chance to take a step back and analyze the play on a macro, rather than micro, level. As I guided the actors through this scene, taking a much more active directorial role, I had to be aware of every single prompt for movement given in the fast-paced dialogue. If the Servant says “[w]ere you the devil I would hold you, sir” (5.31), then they must be holding or physically restraining the Husband. The Husband’s lines “have at his heart” (5.24) and “perish, now be gone” (5.27) must motivate attacking actions, whether toward the younger son or the Wife. Physical cue words are especially prevalent in the second half of the passage, and we played around with the number of ways these cues could be interpreted. We tried variations on the scene: is the Servant armed with a dagger? When should the Husband lose his weapon and how? Should the word “between” (5.30) be performed as a spatial or metaphorical description? In each case, we supported the variants with clues from the dialogue. (It was particularly exciting for me when one of the actors said, “No, I wouldn’t move like that here, because I’ve just said [this].”)

Talking through the Servant and Husband’s fight.

One practical note on vocabulary, however. At future workshops, I need to be more mindful of my own vocabulary (particularly when in a directorial role). There were times during this exercise when I found myself asking if an action or a phrase felt “better” or “worse” than an alternative, and I’d like to reframe this as it implies that we should be working toward a definitively right or wrong answer. This is not the case. In the context of the workshop, where the purpose is to explore a variety of staging possibilities, the idea that something can be “right” or “wrong” should not exist as it restricts our ability to experiment. The fear of being wrong can stop us from trying things that seem off the wall or out of the box. Instead, I’d like to adjust how I ask questions, focusing not on right or wrong but on how natural a choice feels and why. If something feels unnatural, we can make adjustments; if something feels natural, we can use it to guide further exploration. Either way, we’re learning.

Because practice-as-research work can be a bit tricky to describe effectively, I welcome the chance to discuss this workshop further. Please do leave a comment below so that we can continue this dialogue about language and performance in action.