Last weekend (15-16 June), Cultures of Performance hosted two workshops at the 2018 MEMS Festival. While upcoming blog posts will highlight the individual workshops, I wanted to note some parallels between the workshop material and one of the paper presentations I was able to see during the Festival.

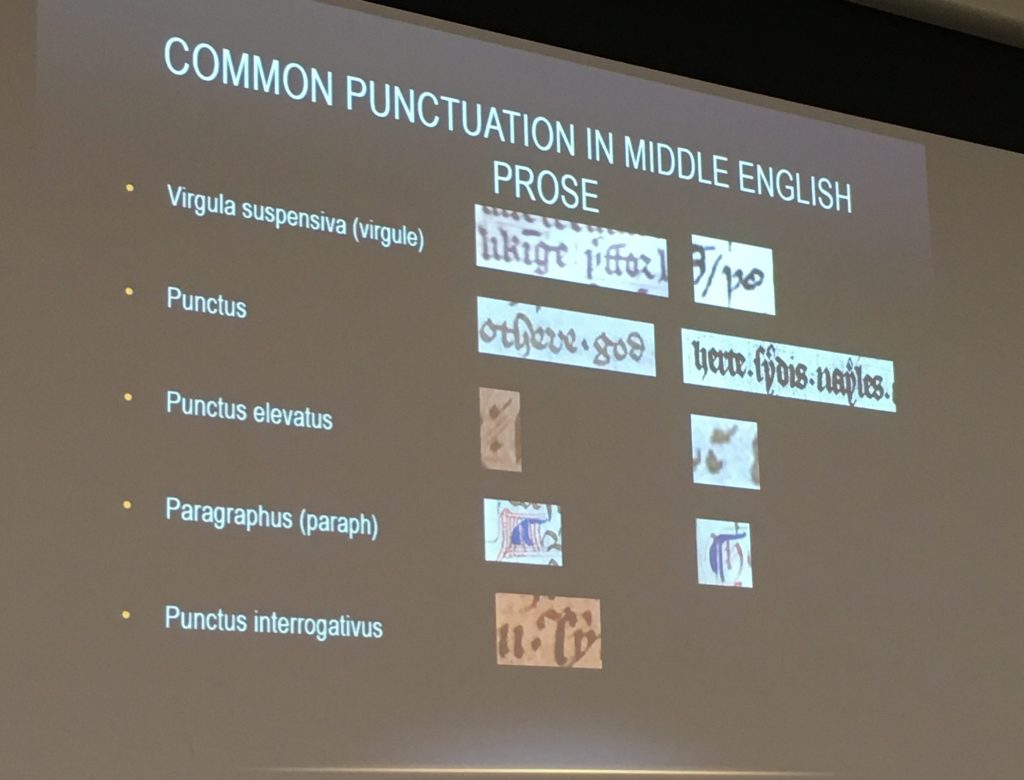

I’m less familiar still with the medieval period, so Dr Ryan Perry’s workshop on Middle English punctuation and the effect it has on reading as performance was largely new material for me. Ryan took us through five common types of medieval punctuation marks: the virgula suspensiva (or virgule), punctus, punctus elevatus (also known as the punctus’ snobby friend), paragraphus (or paraph), and punctus interrogativus. (Live-tweeting this workshop proved to be quite difficult, as the names of these punctuation markers played absolute havoc with my phone’s autocorrect function.)

PowerPoint slide from Dr Perry’s workshop, “Pause, and Effect: Performing Medieval Prose”

While Ryan had a few pictures of these marks in use, the bulk of the workshop was devoted to “clean” copies of the three prose manuscript texts. He asked us, the attendees, to take on two roles during the workshop: that of scribes, helping to punctuate these texts ourselves, and that of active listeners, hearing these texts read aloud. We were able to hear each text twice, with their original punctuation and the punctuation we chose for them. It was fascinating to hear the ways in which different punctuation “changed” these texts — the second versions that we helped to create had completely different flows than the originals. While we punctuated them based on our modern sensibilities, the original manuscripts seemed almost able to do more with less. They were not overly punctuated (in fact, text number three had no original punctuation!) but they sounded direct, pauses and breaths fell in natural places, and the texts didn’t feel in any way awkward, structurally incorrect, or unsound.

Ryan noted in his abstract that modern editors often change and reposition the punctuation marks used in these medieval texts. I think we, unknowingly, were guilty of doing the same. However, hearing the texts challenged and changed my approach to them. What we often say about dramatic texts proves true of these Middle English prose texts as well: they were meant to be performed. While we inserted punctuation into these manuscripts in our small groups, the texts sounded flat and really only existed on the page. When read aloud, however, the performative quality they gained shaped our comprehension of the texts and the stories they told. This is partially a credit to their reader, fellow MEMS doctoral researcher, Jon-Mark Grussenmeyer (who will be blogging about his experience in the workshop). But it’s also a credit to many of the scribes who wrote or copied these manuscripts — just not the scribes from text three, they were completely unhelpful. These scribes were writing with a keen attention to performance and the performative rhythms of both a reader’s delivery and an audience’s reception of this prose. This maps onto the goals of this research cluster perfectly: we aim to study a range of performance events, and this is not limited to medieval and early modern drama.

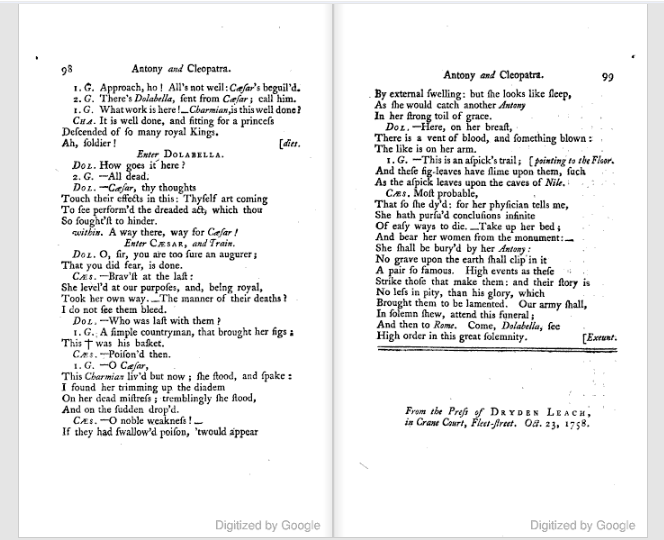

Having said that, I’m now going to discuss one of the Festival’s papers on dramatic, theatrical performance. On the second day of MEMS Fest, Dr Ivan Lupić (Stanford University, Department of English) gave a paper on Edward Capell and David Garrick’s “restoration” of William Shakespeare’s plays. In discussing Capell’s “acting edition” of Antony and Cleopatra, Ivan highlighted a system of punctuation-like symbols, used by Capell and Garrick to put theatrical meaning onto the printed page. There were marks for a change of address, asides, gestures, and even irony. These symbols were apparently

intended to replace stage directions (both original and editorial), unless further clarification was needed. This text then has multiple purposes: it used the printed page as a performance script — this edition was specifically “Fitted for the Stage” according to the title page — but was also available in print for commercial purchase. It was meant to guide actors in a stage performance, but presumably could have been used to shape private readers’ performance as well.

The final two pages of Edward Capell’s edition, with punctuation symbols and stage directions. (Photo credit: Google Books)

I was struck by this serendipitous through-line from the 14th century to the 18th century drawn by our workshop on Middle English prose and this paper on Shakespearean editing for performance. Even with so much distance between them (as, for example, different types of texts and disparate subject matter, not to mention their time periods), they were all four formatted to help readers navigate the text. In the three manuscripts and this printed edition, forms of punctuation were used to encode performance, whether by readers or actors. This is certainly something I’ll be keeping an eye on, going forward in my own research; both this workshop and paper were excellent, timely reminders of the kinds of questions I should be asking when approaching a play-text: where are the natural breaks in lines of verse when read aloud? Do they necessarily match the punctuation? Is this punctuation “original” (with all the authorial and scribal baggage that accompany that term) or inserted by a printer or editor? And most importantly, am I reading this text with a mind towards its performance? As I reflect on these questions, I’m aware of how greatly I appreciate the fact that they were approached collaboratively at MEMS Fest. These are not questions or reminders that we are each thinking about solely on our own, rather we’re discussing them and picking them apart as a research cluster, as willing workshop participants, and as engaged conference delegates. After this past weekend, I’m very much looking forward to collaborating on these questions (and developing new and further questions) during our future Cultures of Performance workshops.