Dr David Rundle, Natalie Tolentino and Jemima Bennett develop methods for manuscript fragment preservation to be applied in libraries and archives.

When Dr David Rundle studies a manuscript, he doesn’t just see an ancient document, he also sees a living, breathing connection to the past alive with possibilities in the present. Dr Rundle knows that for every manuscript he sees, many more have been lost. And like any good sleuth, he starts by asking questions: why did a particular manuscript survive? What was its original form? What has been lost, repurposed or recycled?

Dr Rundle believes expanding the number of manuscripts available digitally will have a significant impact on not only the study of these remaining works but also on the public’s appreciation and understanding of how, when and why these manuscripts were cannibalized for the purpose of creating new books and other items. Understanding the social and practical motivations for rejecting or recycling manuscripts can help us evaluate today’s patterns of consumption and disposal of items we use routinely.

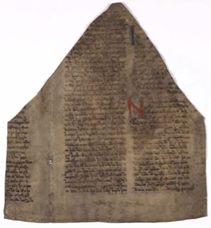

Manuscript fragments used to line a skirt.

Bishop’s mitre made from a manuscript fragment.

In the study of lost manuscripts, Dr Rundle underscores that manuscript fragmentation is not a past process; it is still happening today. Book buyers frequently pull apart 16th-century and later volumes to sell individual folios to collectors, thereby destroying the whole yet increasing access to knowledge of its parts. In the early modern period, to create a book often meant destroying a book or working with destroyed books which meant many manuscripts led plural lives.

University of Kent PhD researcher Natalie Tolentino is working with Dr Rundle and Canterbury Cathedral to uncover the previous lives of the Passional, which spans seven volumes and was written and decorated in the Cathedral’s scriptorium in the 12th century. Using a handheld UV light, she is discovering text that has been erased or otherwise lost. These discoveries are exciting, however, Tolentino cautions that while ruination seduces with the optimism of reconstruction, nothing can—or should—erase the many lives this manuscript has led.

UKC PhD researcher Natalie Tolentino working with the Passional.

Similarly, fellow University of Kent PhD researcher Jemima Bennett is studying the practice of using dismantled manuscripts as book bindings. Much like today’s practice of selling individual parts of books, Bennett’s research is revealing the use of fragments in the early modern commercial book trade, specifically their use as book bindings. By studying examples in the University of Oxford’s Bodleian Library, she hopes to unlock answers to why certain materials, such as liturgical manuscripts, were used for certain volumes and why the orientation of fragments changed between the 15th and 16th centuries. For example, in the later Middle Ages, fragments were generally bound upright, allowing the re-used text to be easily read. However, in the 16th century, fragments were bound on their sides or upside down, denying the textuality of the fragment by making it symbolically illegible and placing greater value on the parchment itself rather than the text.

UKC PhD researcher Jemima Bennett presenting her findings on fragments as bindings.

Working with Dr Rundle, both researchers’ discoveries will ultimately lead to guidance on best practices for fragment preservation that will aid librarians and curators in their efforts to protect these textual treasures and prolong their plural lives. [RG]