For over 350 years, South American cinchona bark provided the only effective cure for malaria known by the West, giving the cinchona tree global significance...

Rooted in the Greek words pharmakon [drug] + gnosis [knowledge], the study of pharmacognosy included understanding drug origins, identification, analysis and quality control: an essential skill for the medically trained. Quinology was a distinct subset of the discipline that evolved in the long nineteenth century. It focused upon the Andean native, fever tree (Cinchona spp.), the origin of the antimalarial drug quinine.

Cinchona bark and bark in a leather ’seron’, which protected it on the long ship journeys. Wellcome Collection.

For over 350 years cinchona produced the only effective cure for malaria known by the West and its importance cannot be overstated. The tree’s medicinal use developed sometime in the early seventeenth century after the Spanish colonists brought particularly virulent forms of malaria to South America. The bark of the local tree provided the cure and by the 1750s, it was being regularly exported to Europe and became one of the most in demand drugs. However, its remote origins, confusing botany, variable bark appearance, adulteration and slow development of effective dosage meant that there was suspicion around the bark’s effectiveness.

Spanish botanists and cinchona bark

Spanish botanist, Hipólito Ruiz López (1754-1816).

A major Spanish expedition, La Real Expedición Botánica al Virreinato del Perú (1777-1816), aimed to capture the botany of the colonies and helped to clarify some of the most pressing questions held by European scientists. It was led by botanists Hipólito Ruiz López (1754-1816) and José Antonio Pavón Jiménez (1754-1840) who had particular instructions to gather more knowledge on cinchona. They made large herbarium and bark collections of the tree, which now lie at Real Jardín Botánico de Madrid and the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

The front piece of Quinologia (1792). Wellcome Collection.

Ruiz and Pavón produced two publications on cinchona, the Quinologia (1792) and the Suplemento a la Quinologia (1801). Linking both titles was the Spanish word for the tree, derived from the Indigenous Quechua tribe’s name for the bark, Quina. Linked with the Latin suffix, ologia, meaning the ‘study of’, the works were botanical examinations of the tree attempting to clarify its species and link them to trade bark types. These publications planted a seed for quinology, but the discipline wasn’t yet fully formed.

Attempts at cultivation

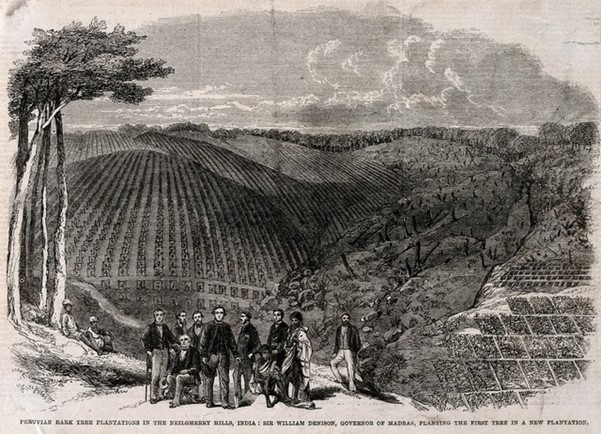

As more and more information accrued, demand for cinchona only increased. This intensified after 1854 when its use as a malarial prophylactic developed. Its control by European Empires therefore became more pressing as it was clear it could be used for protecting workers’ health in the ever-growing tropical colonies. Talk of its cultivation arose.

Cinchona is a problematic genus, it presents a wide variation in its morphology and chemistry depending on how and where it is grown. This caused much confusion amongst botanists and pharmacologists, with hundreds of species erroneously described. Attempts at cultivation by the Dutch in 1850 had already led to Javanese plantations full of a medically ineffective species. Therefore, focused efforts were required to target a tree with medicinally and economically valuable bark.

Cinchona’s active constituent, quinine, had already been isolated by the French pharmacists in 1820, who named it based on the French Quechua-derived name, quinquina. This event produced a tool for measuring which trees produced the most quinine-rich barks. Within a few years, quinology had emerged, combining traditional botanical knowledge with this novel chemical technique.

Sir W. Denison and others planting the first quinine tree in the Neilgherry hills, India. Wood engraving by M. Jackson, 1862. Wellcome Collection.

The development of quinology

Who practised this science? In 1866, Clements Markham, the man involved in taking cinchona from South America for British-Indian plantations bemoaned the difficulties in finding a quinologist to oversee the project:

‘I would not venture to express any further opinion respecting [appointing a quinologist] if it was one of an ordinary character, but in truth the number of men who are capable of filling it is so exceedingly small that the choice is narrowed, so far as I am aware, and I have made diligent enquiries, almost to one man. There are several learned quinologists in Europe, some like M. Delondre, in extreme old age, while others such as Dr. Phoebus, M. Guibourt, Mr. Weddell, Mr. Howard, Mr. Hanbury, Carl Zimmer & C. are not in a position to accept an offer of this kind.’

The list of seven names he gave was noteworthy: most are pharmaceutical manufacturers, located at the forefront of industrial research and development in the top chemical extraction countries of Europe: Germany, France, Netherlands and Britain. The discipline developed alongside the nineteenth-century alkaloid industry growth and the upscaling of drug production from pharmacy to factories.

John Eliot Howard (1807-1883), British quinologist. Permission of Tabitha Fox.

The British man on Markham’s list, John Eliot Howard (1807-1883), was a key quinologist who had built the largest known collection of cinchona bark. He hailed from a large-scale pharmaceutical manufacturer, Howards and Sons, which produced tons of quinine per year. Howard had the tools and financial backing to become established as a leading expert, developing specialist knowledge on the factory floor. He supplemented this with growing trees in his Tottenham garden and the maintenance of extensive correspondence networks across Europe and South America.

Cover of John Eliot Howard’s Quinology of the East Indian Plantations (1869-76) showing a branch of cinchona. Courtesy of Hindman Auctions.

Howard published profusely on the genus describing in-depth its botanical, chemical, microscopic and macroscopic analysis. This project culminated in two influential, full-colour quinological books, The Nueva Quinologia of Pavon (1862) and The Quinology of the East Indian Plantations (1869-76), distributed across Europe and to British-Indian planters. Interestingly, Howard’s skills overshadowed those of experts at Kew, and he became the acknowledged expert. This resulted in Howard consulting for the British-Indian government on which species to profitably grow.

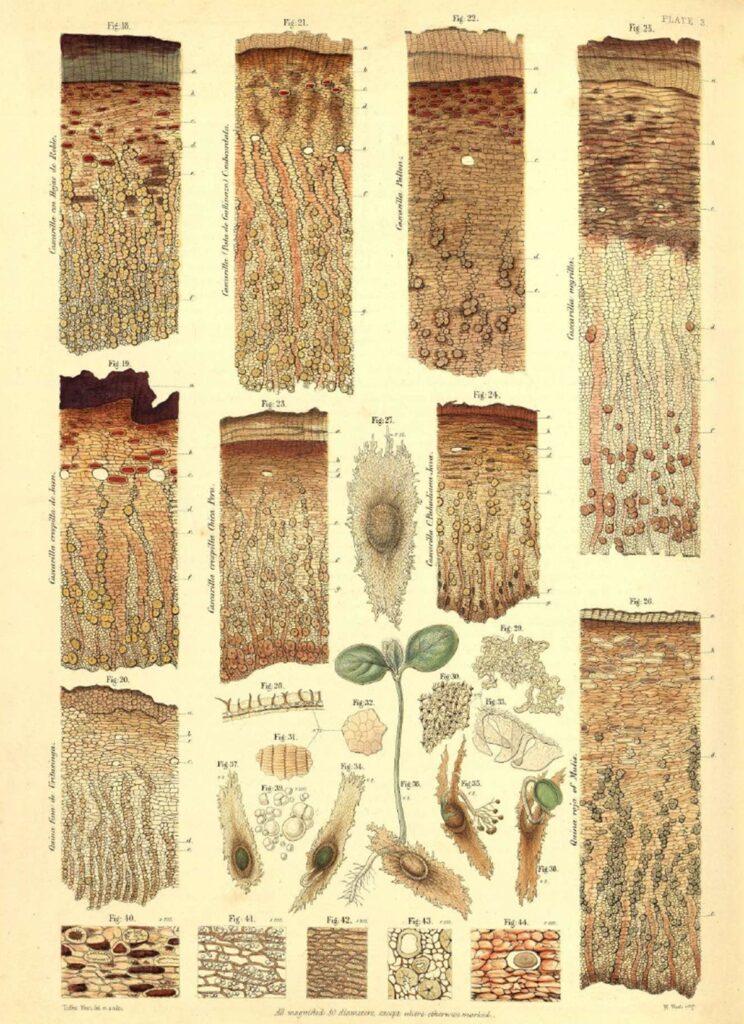

Microscopic analysis formed part of the tools of quinology. This plate was drawn by microscopist Tuffen West (1823-1891) for quinologist John Eliot Howard’s Nueva Quinologia of Pavón (1862), an analysis of the cinchona genus and its alkaloids. Wellcome Collection.

Gradually, the importance of quinology dwindled by the early twentieth century. However, the distinct subset of pharmacognosy developed in the nineteenth century at the intersection of histories of chemistry and botany and deserves more recognition of its impacts on imperial projects.

References

- Deb Roy, R. (2017). Malarial subjects: Empire, medicine and nonhumans in British India, 1820–1909. Cambridge University Press.

- Dhami, N. (2013). Trends in Pharmacognosy: A modern science of natural medicines. Journal of Herbal Medicine, 3(4), 123-131.

- Klein, W., & Pieters, T. (2016). The Hidden History of a Famous Drug: Tracing the Medical and Public Acculturation of Peruvian Bark in Early Modern Western Europe (c. 1650–1720). Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, 71(4), 400-421.

- van der Hoogte, A. R., & Pieters, T. (2014). Science in the service of colonial agro-industrialism: the case of cinchona cultivation in the Dutch and British East Indies, 1852–1900. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part C: Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences, 47, 12-22.

- Howard, J.E. (1862). Illustrations of the nueva quinologia of Pavon. Lovell Reeve & Co.

- Howard, J.E. (1869-76). The quinology of the East Indian plantations. Lovell Reeve & Co.

- Wallis, P. (2012). Exotic drugs and English medicine: England’s drug trade, c. 1550–c. 1800. Social history of medicine, 25(1), 20-46.

- Walker, K. (2023). The making of a quinologist: Cinchona, collections and science in the work of John Eliot Howard (1807-1883). [Doctoral Thesis]. Royal Holloway, University of London.

Author

Dr Kim Walker has recently completed a Doctoral Training Partnership between the Historical Geography Department, Royal Holloway and the Economic Botany Collection, Royal Botanic Gardens Kew. She works on the history of medicinal plants, with a focus on nineteenth century alkaloids. She is also the author or Just The Tonic, (2019, Kew publishing), a natural and social history of tonic water.

- Email: kwalker.research@gmail.com

- Twitter: @kim_wyrt

- Instagram: @kim_walker_research