The sator square, not only migrated geographically, but through belief systems and across time periods, demonstrating the enduring grip it exercised on the classical and medieval imagination, its power both medical and social...

The use of charms, a genre of spoken or written formulae, used for healing and other purposes, was a common practice throughout medieval and early modern Europe. The surviving corpus of charms from England from this period share strong commonalities with those circulating on the continent, both in terms of purpose, that is, what they were used to treat, and motif, for example the key people or characters they referenced, biblical narratives they drew on, or the specific formulae of their invocations. As charms migrated from the continent to England and vice versa, there is evidence that they underwent both casual change and careful repetition.

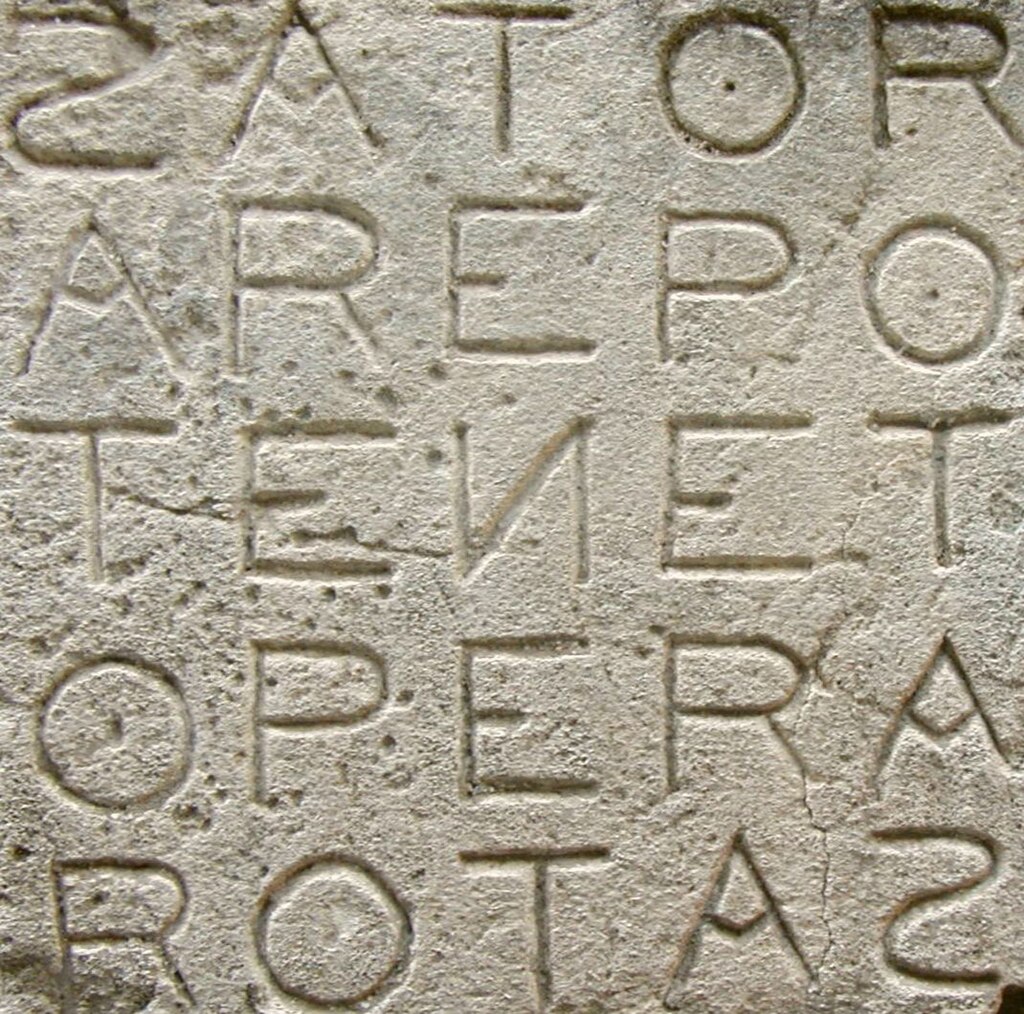

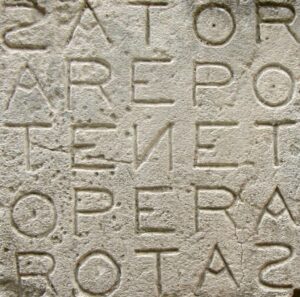

A Sator Square etched onto a wall in the medieval fortress town of Oppède-le-Vieux, France. Taken by M. Disdero.

This blog post will explore how such change and repetition, preservation and adaptation, are evidenced by one particularly famous charm known as the sator square. It will show how formulae that were thought to be effective were not only disseminated widely, crossing geographical borders, but were also adapted, for example to address additional concerns and anxieties.

The sator square is one of the most well-known magical formulae. It has even inspired Hollywood movies such as Christopher Nolan’s film Tenet released in 2020 and was recently described by The Daily Telegraph as ‘a meme of the ancient world’. The Sator Square inspired the film’s title, the character names of Sator and Arepo, the location of the opening sequence (Opera), and the name of Sator’s security company (Rotas).

The origins of the sator square

A palindromic square, it is made up of five words, sator arepo tenet opera rotas, and was originally thought to be a Christian symbol, particularly when, in the 1920s, it was discovered that the words in the square were an anagram of Paternoster, written out twice in cruciform, with the additions of the letters A and O representing the Greek Alpha and Omega.

The Christian significance of the word square, however, was undermined by the discovery of the palindrome scratched into a column in Pompeii. This has been dated to between 50 and 70 AD, and before there was any known Christian presence in Pompeii. The most likely explanation for the formula may therefore be that it was simply a clever palindrome which became widespread due to its particularly pleasing nature.

While the word square’s origins are likely pre-Christian, and the anagram of the Paternoster is a particularly extraordinary coincidence, by the sixth century the formula was definitely being represented in a Christian context. A sixth century bronze amulet from Asia Minor, now held in a Berlin museum, features the sator square in Greek characters, accompanied by two fish and the word ICHTHUS which stands for Christ.

A migrating charm

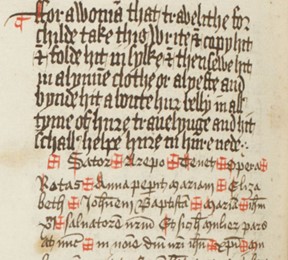

The sator formula migrated, not only across Europe, but throughout the world, and serves many purposes. In Germany, for instance, it is particularly associated with the ability to extinguish fires, but in England, it is most commonly found in medical collections as a charm for childbirth. The earliest attestation of the formula in an English manuscript serves just such a purpose. In the eleventh-century manuscript Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 41, in the margins of an English translation of Bede, are a number of charms, including one for childbirth. Here, the sator arepo formula is inserted where the name of the Trinity would usually be expected, has been fully integrated into a Christian belief system. The words could work as part of a spoken formula, but more often they were written out and tied to the labouring mother’s body, as in the below fifteenth-century example.

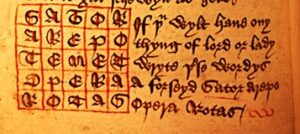

The sator formula for childbirth, San Marino, Huntington Library, MS HM 64, fol.111v.

Towards the end of the medieval period, there is evidence that the sator square, in textual amulet form, was being adapted into a ritual to address social, rather than medical concerns. Two surviving texts in late-fifteenth century English manuscripts include instructions to draw the square on a piece of virgin parchment using the blood of a bird, and carry it upon your body. One, in English, instructs the practitioner to leave the parchment on an altar for two days, sprinkled with holy water, after which the bearer will have anything they ask for from a lord or lady. The other, in Latin, suggests that carrying the word square will give you grace in the eyes of everyone you meet. The efficacious magical formula of the word square has been retained, but the ritual is now intended to address a social, rather than a medical concern.

If þou wylt have ony thing of lord or lady wryte þesse wordys a forsayd sator arepo opera rotas wit the blod of a dowe and þanne strenkele þer-on haly water and þanne ley it ii deyes on an auter and þanne bere it wt þi right hand and what þou axe rightfully thou xal have it wt owtyn dowte.

London, British Library, Additional MS 12195, fol. 126v.

This short overview of how the sator square, not only migrated geographically, but through belief systems and across time periods, demonstrates the enduring grip it exercised on the classical and medieval imagination. Its pleasing palindromic structure and the – almost unbelievable – way that it spells out the Paternoster lent it an esoteric quality that enhanced its perceived power. This power lies at the root of both the preservation and adaptation of the sator square throughout the centuries and as it moved across continents. While the efficacious formula itself was carefully retained, the way in which it was used, and even the ritual components associated with it, underwent creative adaptation. If the words, repositories of numinous power, could put out house fires or ease the pain of a woman in labour, why could they not win their bearer love and favour? Like many other charms from the medieval and early modern period, as this formula circulated its users sought to harness its power but apply it to other situations, and provide solutions to some of the other problems, concerns, or desires that preoccupied the premodern populace.

References

- Smallwood, T.M., ‘The Transmission of Charms in English, Medieval and Modern’, in Charms and Charming in Europe, ed. by Jonathan Roper (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004), pp. 11–31.

- Jones, Peter Murray, and Lea T. Olsan, ‘Performative Rituals for Conception and Childbirth in England, 900–1500’, Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 89.3 (2015), 406–33.

- Sheldon, Rose Mary, ‘The SATOR Rebus: An Unsolved Cryptogram?’, Cryptologia, 27.3 (2003), 233–87.

- Skemer, Don C., Binding Words: Textual Amulets in the Middle Ages, Magic in History (Philadelphia: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2006).

Author

Heather Taylor is a final year PhD candidate in the Centre for Medieval and Early Modern Studies at the University of Kent. Her research, funded by a Vice Chancellor’s scholarship, examines ‘non-medical’ charms and experimenta in late-medieval manuscripts, with particular focus on those which seek to control aspects of social relations. Her research explores what these reveal about the prominent concerns of the period and how they resonate with our broader understanding of social attitudes and anxieties in the Middle Ages.

Email: hat5@kent.ac.uk

Twitter: @het_tay