The Christine and Ian Bolt Scholarship was set up in memory of Christine Bolt, Emeritus Professor of History at the University of Kent. The award supports postgraduate students working across Social Sciences and Humanities whose area of research has a significant American element to undertake a period of research in the United States. Shelley Angelie Saggar, a PhD researcher in the School of English/Centre for Indigenous and Settler Colonial Studies was awarded the scholarship in 2021. In this post she reflects on her experience.

Last spring I was awarded a Christine and Ian Bolt scholarship to support a research trip to the United States as part of my PhD in English Literature. My doctoral project examines how Indigenous writers and filmmakers from Turtle Island/North America and Aotearoa/New Zealand have represented the ethnographic museum. As part of my research I was keen to spend time in the institutions that my primary texts allude to and, at times, directly address, in fiction, poetry, and film. After many Covid-related delays, I arrived in New York in May 2022 to begin a busy six weeks of meetings, museum visits, and writing.

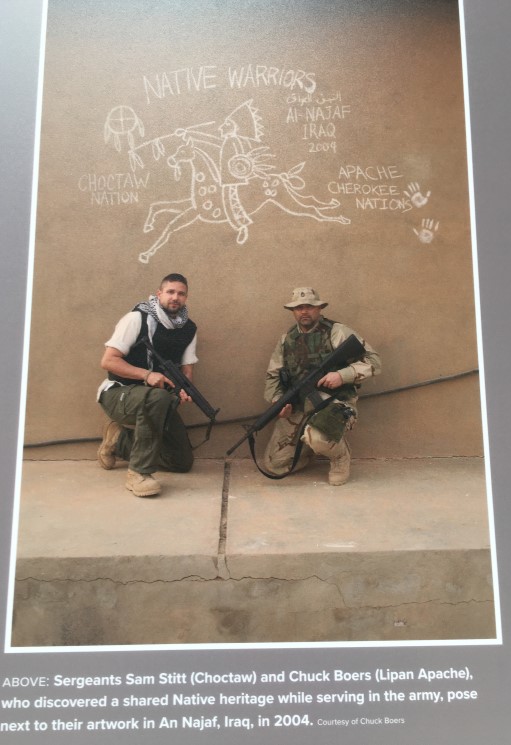

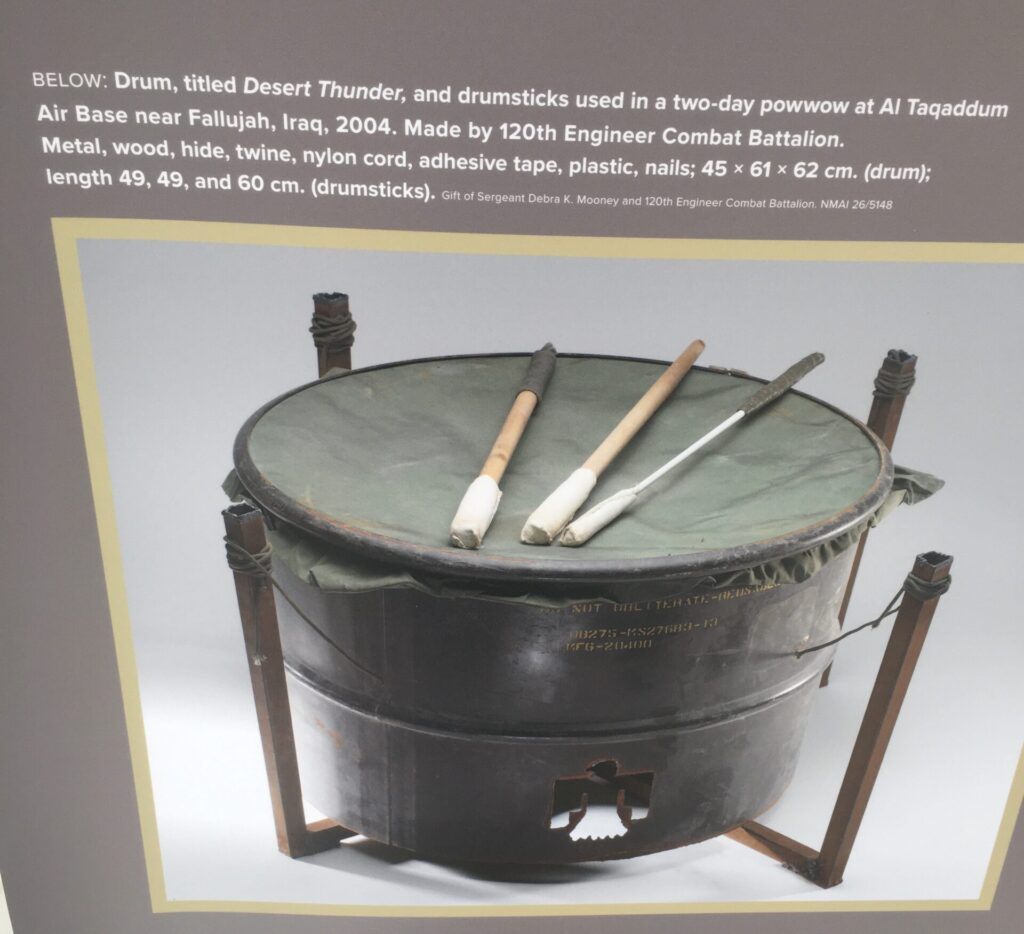

My itinerary was influenced by the focus of the texts I study. At times, there seemed to be an infinite number of potentially crucial places to spend time in, however, after much refining, I narrowed my plans down to three sites: New York, Washington D.C., and the East Bay. In New York, I met with Sarah Khan, Artist in Residence for the Art HX project which explores visual and medical legacies of British colonialism, and Dr Robbie Richardson, previously at the University of Kent and now an Assistant Professor at Princeton University. I visited most of the large galleries, many of which hold permanent collections of Native American material, in addition to the National Museum of the American Indian’s NYC campus, which is housed in the Alexander Hamilton Customs House – an impressive and thought-provoking setting for the museum’s collections. My main interest, however, was determined by Ojibwe poet Heid E. Erdrich’s ‘Not Seeing Ground Zero in 2005’, a poem from the 2008 collection National Monuments. The poem describes a visit to New York City in the aftermath of 9/11 and the first chapter of my dissertation reads ‘Not Seeing’ in light of the disparities it highlights between the dismissive and often disturbing treatment of Indigenous ancestral remains in museum collections and the veneration of those killed in the September 11th attacks. As such, the NMAI’s Why We Serve exhibition, which opened in 2020 and has a small feature in the NYC campus, was intriguing as an illustration of the tensions between Indigenous critiques of American imperialism (such as those made in Erdrich’s poem) and the complex relationship Native American peoples have with military service.

Sergeants Sam Stitt (Choctaw) and Chuck Boers (Lipan Apache) pose next to their artwork in An Najaf [sic], Iraq, in 2004. Photo author’s own.

Drum, titled ‘Desert Thunder’ that was used in a powwow near Fallujah in 2004. Image author’s own.

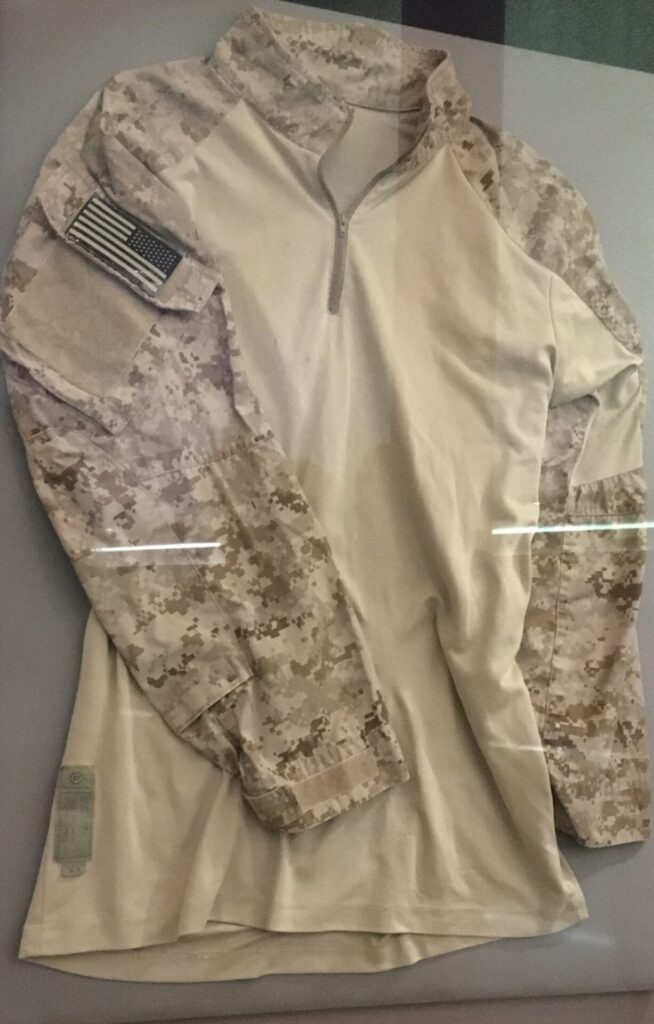

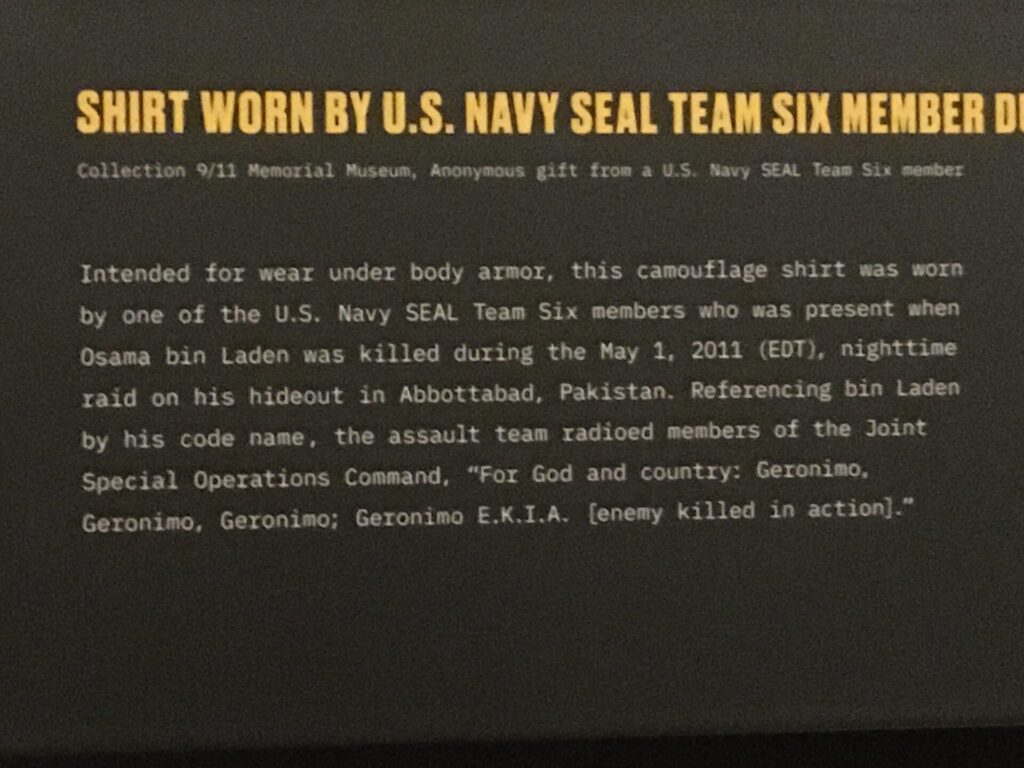

Building on my research interest in Indigenous perspectives on the War on Terror, I headed to both the National September 11 Memorial & Museum on Greenwich Street and the 9/11 Tribute Museum, located just around the corner from the former Ground Zero site. The two museums, which take strikingly different curatorial approaches, highlight Native American narratives in divergent ways; whilst the Tribute Museum attempts to incorporate stories of Kahnawake Mohawk ironworkers into an account of multicultural cohesion in the wake of disaster, the National Memorial & Museum features just a single allusion to indigeneity; a camouflage shirt worn by a member of the Navy SEAL team who was part of the raid on Osama bin Laden’s Abbotabad compound in 2011. The shirt is displayed with a reference to bin Laden’s codename: “Geronimo”; the intimation serves as an example of what Chickasaw theorist Jodi Byrd describes as ‘the transit of Empire’ – the ways in which “Indians” function and feature in the U.S. imperial imaginary across various military contexts.

Photograph taken in the 9/11 Memorial & Museum of a shirt worn by a U.S. Navy SEAL Team Six member during the raid on Osama bin Laden’s House. Image author’s own.

Photograph of a museum label taken in the 9/11 Memorial & Museum. The caption reads: ‘Intended for wear under body armor, this camouflage shirt was worn by one of the U.S. Navy SEAL Team Six members who was present when Osama bin Laden was killed during the May 1, 2011 (EDT), nighttime raid on his hideout in Abbottabad, Pakistan. Referencing bin Laden by his codename, the assault team radioed members of the Joint Special Operations Command, “For God and country: Geronimo, Geronimo, Geronimo; Geronimo E.K.I.A. (enemy killed in action).”‘ Image author’s own.

From New York I took the train to Washington D.C. Visiting the Smithsonian complex was top of my list and the National Museum of the American Indian, the National Museum of African American History and Culture, and the National Portrait Gallery were particular highlights. I was lucky to be in town at the same time as Allison Morehead, an Associate Professor in the Department of Art History and Art Conservation at Queen’s University, who was in D.C. as an Ailsa Mellon Bruce Visiting Senior Fellow at the Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts at the National Gallery of Art. Professor Morehead had invited me to participate in a curated panel at the Art HX ‘Curative Spaces’ symposium earlier in the spring, and it was great to finally meet in person.

The East Coast portion of the trip was always planned to be packed with as many meetings and visits as possible. In California, I was keen to slow the pace down and focus on writing. Until I left London I had been drafting the first chapter of my dissertation, a section of which discusses the treatment of Indigenous ancestral remains in Heid Erdrich’s National Monuments. The ‘Kennewick Man’ sequence is primarily set on the campus of the University of California’s Berkeley campus. Bringing together my research into the representation of Native Americans in New York City’s 9/11 memorials and museums with the experience of working from the UC Berkeley campus, I spent the final weeks of the trip in the Ethnic Studies Library, where, with the brilliant help of the librarians, I wrote an article on the themes of national violence and neocolonial mourning in Erdrich’s collection, which is currently under consideration by the Studies in American Indian Literatures journal.

Overall, it was a privilege to be able to travel to the US for such an extended period of time. On returning, I feel better equipped with an atmospheric understanding of the spaces that feature in the texts I work on. As a result of connections made and cemented during the trip, I have been invited by the Art HX team to take up a virtual Interpretive Fellowship for the 2022/23 academic year. During this, I will produce a critical-creative response to the project’s object database, relating to the one of the initiative’s three areas of focus: ‘Cultivating Care’, ‘Pathologies of Difference’, and ‘Medicalized Space’. This is a brilliant opportunity to work more closely with a fantastic group of scholars and creative practitioners and I am so grateful to the Christine and Ian Bolt Scholarship for making these connections and research constellations possible.

You can read more about Shelley’s research project here.