Join us for our first work in progress session with Dr. Michael Falk, Lecturer in 18th-century studies, University of Kent

6 Nov. 2020 from 4pm

For zoom link and pre-circulated paper contact us at indigenousstudies@kent.ac.uk

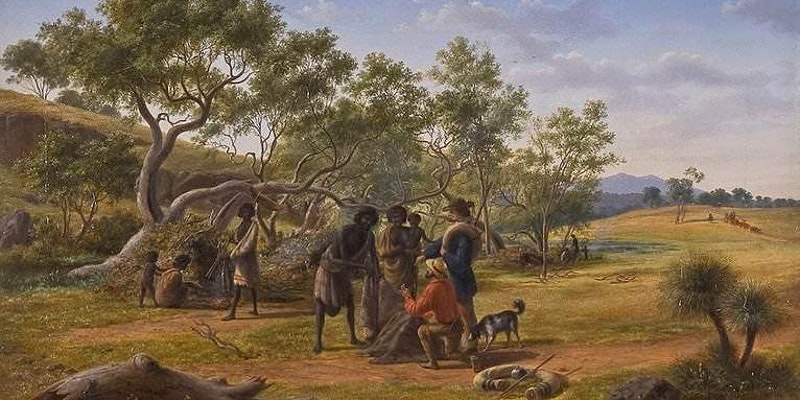

Nature was a great problem for the first British settlers in Australia, for many reasons. It was hard to grow European crops in infertile soils and with such varying rainfall. Fires, floods and venomous creatures threatened the unwary. And of course the land was already in the possession of Aboriginal Australians, who resisted European invasion by guile and force. But despite these hostile elements, the Australian environment was strangely welcoming to Europeans. The settlers rapidly acquired longer lives, greater wealth, and more robust and plentiful children than their British counterparts. Those same Aboriginal inhabitants who resisted their rule were also valuable allies, assisting the settlers as guides, stockmen, labourers, domestics, midwives, companions, or more distressingly as sex workers. Australia presented a complex and contradictory face to its new inhabitants.

This challenged the colony’s writers. How could they describe this environment using the language they had learned in Europe? Louisa Anne Meredith captured the problem beautifully in a passage on that most Australian of plants, the eucalyptus:

They are, however, evergreens, and in their peculiarity of habit strongly remind the observer that he is at the antipodes of England, or very near it, where everything seems topsy-turvy, for instead of the “fall of the leaf,” here we have the stripping of the bark, which peels off at certain seasons in long pendent ragged ribands, leaving the disrobed tree almost as white and smooth as the paper I am now writing on. (Notes and Sketches of NSW, 1849, p. 51)

Meredith hits on two problems the settlers had with Australian nature. First, there were Australia’s surprising, ‘topsy-turvy’ elements, which forced the settlers to rethink apparently familiar notions such as the ‘seasons’. Second, there was Australia’s uncanny blankness or indescribability. When the bark was peeled away, Australian nature was ‘as white and smooth as … paper’. It appeared to say nothing, to make no distinctions, to be without meaning. The settlers confronted an Aboriginal Nature, which sometimes seemed wordless, and sometimes spoke in a foreign tongue.

In this paper, I will show how the problem of Aboriginal Nature both inspired and warped Australian Romanticism. It was the core problem for Australia’s best early nature poets, such as Charles Harpur, Emily ‘Australie’ Manning, Eliza Dunlop and after them Henry Kendall. Aboriginal Nature broke down the Eighteenth-Century distinction between ‘nature’ and ‘art’. Were Aboriginal people, their songs, dances, words and stories, part of the natural environment or a human addition to it? Was Australia indeed a blank slate just waiting for a new poetry to be written on it, or was Australian poetry burdened from the start with a long and mysterious past? When Aboriginal people spoke through this English poetry—for instance, in Dunlop’s translations of traditional song—did their voice remain their own, or was it the voice of nature? Such questions invigorated the most creative poets, but the early Australian Romantics were also enmeshed in ugly imperialist realities that could warp their vision.