Sarah Smeed reflects on how Indigenous Studies is helping historians of Empire to open the archives of imperialism to a broader range of perspectives.

The study of colonialisms and Indigenous presence garners interest and insight from an eclectic range of disciplines. On May 25th 2020, a wide mix of historians, literatists, Indigenous studies scholars, and Americanists met to discuss Kate Fullagar’s recent work, ‘The Warrior, the Voyager, and the Artist’. One benefit of the current necessity of making such meet-ups digital meant scholars scholars from across the globe were able to join – including the author herself. What followed was an invigorating discussion on methodological approaches, the potential of speculative histories, and how non-Indigenous academics can engage with Indigenous stories.

The legacy of the British Empire is quite difficult to escape nowadays. Fuelled in part by the rise of right wing politics, Brexit, and even in the current situation with COVID-19, in Britain, it feels as though there is a significant renewed ‘Imperial Nostalgia’ for a time where we were seemingly in control. Of course, this is not without criticism – yet, the arguments and discussions surrounding this topic often devolve into a simplified ‘good vs bad’ narrative. Often forgotten from this line of thinking, are the realities of the ways imperial pursuits impacted individuals, and further, how it led to unlikely connections between people from across the globe. Kate Fullagar’s research in ‘The Warrior, The Voyager and the Artist’ serves to bring individual experiences to the forefront of the eighteenth century, providing in her words, “an experiment in New Biography…” Whereas ‘Imperial Nostalgia’ tends to lean heavily on the voices of white men, Fullagar’s work is particularly concerned with amplifying Indigenous voices through navigating the lives of Cherokee diplomat and warrior Ostenaco from the Tellico, and Pacific Islander Mai from Ra’iatea with his travels in the latter half of the century. Their respective visits to London in the eighteenth century were partly framed by meeting with, and being painted by, renowned artist Joshua Reynolds, whose own thoughts towards imperialism were never easily discerned in his career. By considering these three figures and mapping the way their lives were briefly interwoven, Fullagar complicates popular narratives surrounding the British Empire in the eighteenth century, and shows the complexities individuals faced in this era. In her words, a focus on such narratives allows advancement on understanding empire, and one “which should not be to indulge nostalgists but instead to go further in excavating empire’s culture.”[1]

Part of the way Fullagar seeks to do this is by focusing on the figures of Ostenaco and Mai, pulling Indigenous voices front and centre. The study of this period is often dominated by the views of white men – both in historians that write it, and those who author the sources. Indigenous responses are rarely included, and even when they are, they are scarcely the driving force. There is difficulty in attempting to do so, with a lack of written sources, and the moments when they are written about being overshadowed by the role of imperialists. Fullagar’s biographical approach works to limit these issues, portraying Ostenaco and Mai in their moments away from, as well as involved in, imperialism. The focus on individuals further highlights the actions Indigenous peoples took in this century, and how their histories are marked by adaptation, negotiation, and survival. There is a stress on understanding that these lives, whilst different from each other, where also different to lives lived now, and that there is a need to “honor…the diversity and dissonance of the past.”[2] Beyond documenting their respective upbringings, societies, and aims in their visits to London, Fullagar probes the questions of how they felt about their situations. Stipulations on the extent to which they reflected on their experiences are considered throughout. Did they think about Joshua Reynolds beyond when they were painted by him? Not likely. How did Mai feel about the way Reynolds portrayed him as an ‘everyman’ in his famous portrait? He probably understood it was a representation, but not an accurate reflection. How did Ostenaco feel about being a ‘celebrity’ in his 1762 trip? Definitely not fond of the constant staring. This approach allows for a fully rounded idea of who Ostenaco and Mai were, and what they presented to onlookers, as well as how their backgrounds informed them. With this, there is more revealed about the Atlantic and Pacific worlds and how imperialism interceded with both.

Portrait of Ostenaco, 1762, by Sir Joshua Reynolds. Currently on display at the Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

The dichotomy of likeness and difference, as well as identity, are central themes in the book, and ones that resonated with my own research into Native American facial appearance in the eighteenth century. The three men are presented as figures of difference, only united in the ways imperialism led them to cross paths. The title itself relates to this, each man marked by his primary occupation. Each inhabited different areas of the globe, and their experiences of growing up were defined in different societal structures. For Joshua Reynolds, his world was situated in a patriarchal and hierarchical structure, wherein his family’s place in the ‘middling’ part of society allowed him some room to manoeuvre, eventually to a place wherein he was interacting with the aristocracy. In exploring Reynold’s upbringing, Fullagar notes British society in the eighteenth century was marked by changing perceptions of the self – going from being defined by how others related to each other, to “the creation of a private individual soul.”[3] For Ostenaco, born in the 1710s of Tellico in modern day Tennessee, his Cherokee upbringing was matrilineal but not matriarchal, spiritual but not secular. Identity was tied to clanships, and much of Ostenaco’s stake in his diplomatic encounters were based around ensuring the survival of his clan. Mai, born in the middle of the eighteenth century in Ra’iatea, grew up in a society that was patrilineal and hierarchical, where understandings of religion and politics blurred together. Their appearance further solidified their differences. Ostenaco’s Cherokee identity was framed by the application of ochre on the face. For Mai, tattooing the body coincided with important events, the milestones of growing up and his achievements portrayed through ink. The clear pale faced complexion of Reynolds situated him in the Western world. Yet, as Fullagar addresses, “The things that seperate…soon lead to the things that bind.”[4]

Beyond the relationships each held with the imperial world, what prominently struck me throughout the book, especially in the biographical approach, were the markers of similarity that occured in each of the man’s lives. The processes of growing up, the ways in which milestones were recognised and celebrated, the discussions surrounding partnerships and marriages, their relationships with colleagues and adversaries, and ultimately their deaths were shared experiences. The start of the prologue begins with a speech by Reynolds given in December 1776 at Somerset House, with revolutionary warfare brewing in the American colonies. In the talk he emphasised the goal of art was to show “the “general truths” of humanity, which are all indisputably “universal.”[5] In some ways, this approach held some weight. Ultimately, though, imperial pursuits divided rather than united. The neoclassical style that Reynolds sought to emulate through his work focused on what a person could be rather than necessarily what they were, and this conflict of identity seemed prevalent in the visits by Ostenaco and Mai, and in Reynold’s own indecision with his country’s imperialism. To gain from empire was to adapt. Kate Fullagar’s research shows the imperial project in the eighteenth century was not straightforward, and it’s outreach and impact were far-reaching and on going. To better understand it, and to respect those whose lives were affected by it, it is necessary and important to focus on those experiences, and illuminate their voices. Importantly, in the case of Reynolds, Ostenaco and Mai, each created a legacy that involved and shaped the empire but was not wholly defined by it.

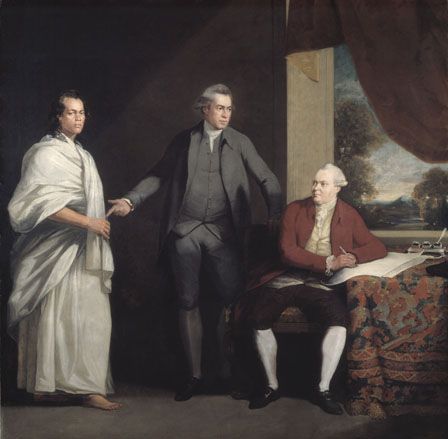

William Parry, Portrait of Omai (c.1753-c.1776/7), Joseph Banks (1743-1820) and Dr Daniel Solander (1736-1782). Image curtesy of the National Museum of Wales.

Discussion surrounding the book focused on methodological approach, and primarily how non-Indigenous scholars can navigate traditional archives and collaborate with contemporary Indigenous groups. As a PhD student investigating the ways Native American facial appearance was depicted from c. 1680 to 1830, hearing established scholars discuss the complexities of conducting such research was both helpful and reassuring. Conversation about Fullagar’s deployment of speculative history and what can be ascertained by an individual’s absence at an event or in conversation, allowed me to reflect on my own research and what there is to be said when appearance was not described. Reading into the silences or the gaps in the archival record can be just as telling as what is explicitly stated. Especially when utilising sources that do not feature Indigenous voices clearly, this is one way to further uncover narratives. Remaining connected has never been as topical as it is now, and so the chance for scholars from different backgrounds to find the links between disciplines and interests through exploring ‘The Warrior, the Voyager and the Artist’ was notable, highlighting the value of such discussions.

[1] Kate Fullagar, The Warrior, the Voyager, and the Artist: Three Lives in an Age of Empire (Yale University Press, 2020) p. 5

[2] Ibid. p. 5

[3] Ibid., p. 45

[4] Ibid., p. 4

[5] Ibid., p. 2

Sarah Smeed is currently a PhD candidate in American Studies at the University of Kent. Her CHASE funded project examines the role of Native American head and facial appearance in Euro-Indigenous relations c. 1680 to 1830. She is broadly interested in cultural encounters, textile history, and presentations of identity. She was recently a 2019/2020 recipient of the AHRC International Placement Scheme, conducting research at the Library of Congress.