Steve Bell

About

Steve Bell was born on 26 February 1951 in Walthamstow, London, where his father was an engineer. Bell was educated at Slough Grammar School, andwas a fan of cartoons from an early age. The family took the Daily Mail, and Bell recalled that it ‘had a superb cartoonist called [Leslie] Illingworth who was a brilliant draughtsman…and Trog [Wally Fawkes], who was big influence on me’: ‘My dad was a great fan of his strip, Flook, and I used to read it. I didn’t understand what it was about but I loved it.’ Bell was also influenced by Ronald Searle, and recalled that the Penguin book ‘Searle in the Sixties’, published in 1964, ‘changed my life’, encouraging him to ‘draw, draw, draw.’

From school Bell went to study art at Teeside College of Art in Middlesbrough, but, disillusioned with the College’s narrow definition of art, he left to study art and film at Leeds University. At Leeds he met Kipper Williams. Bell graduatedin 1974, and, after taking a teaching certificate at St Luke’s College, Exeter, went to teach artat a secondary school in Birmingham. He later remembered it as ‘hell on earth’: ‘The worst year of my life…I just wasn’t suited to it.’ Part of the problem was being in a position of authority. ‘I always hated authority’, Bell recalled, ‘I had no sense of my authority as a teacher, so I was hopeless at it.’

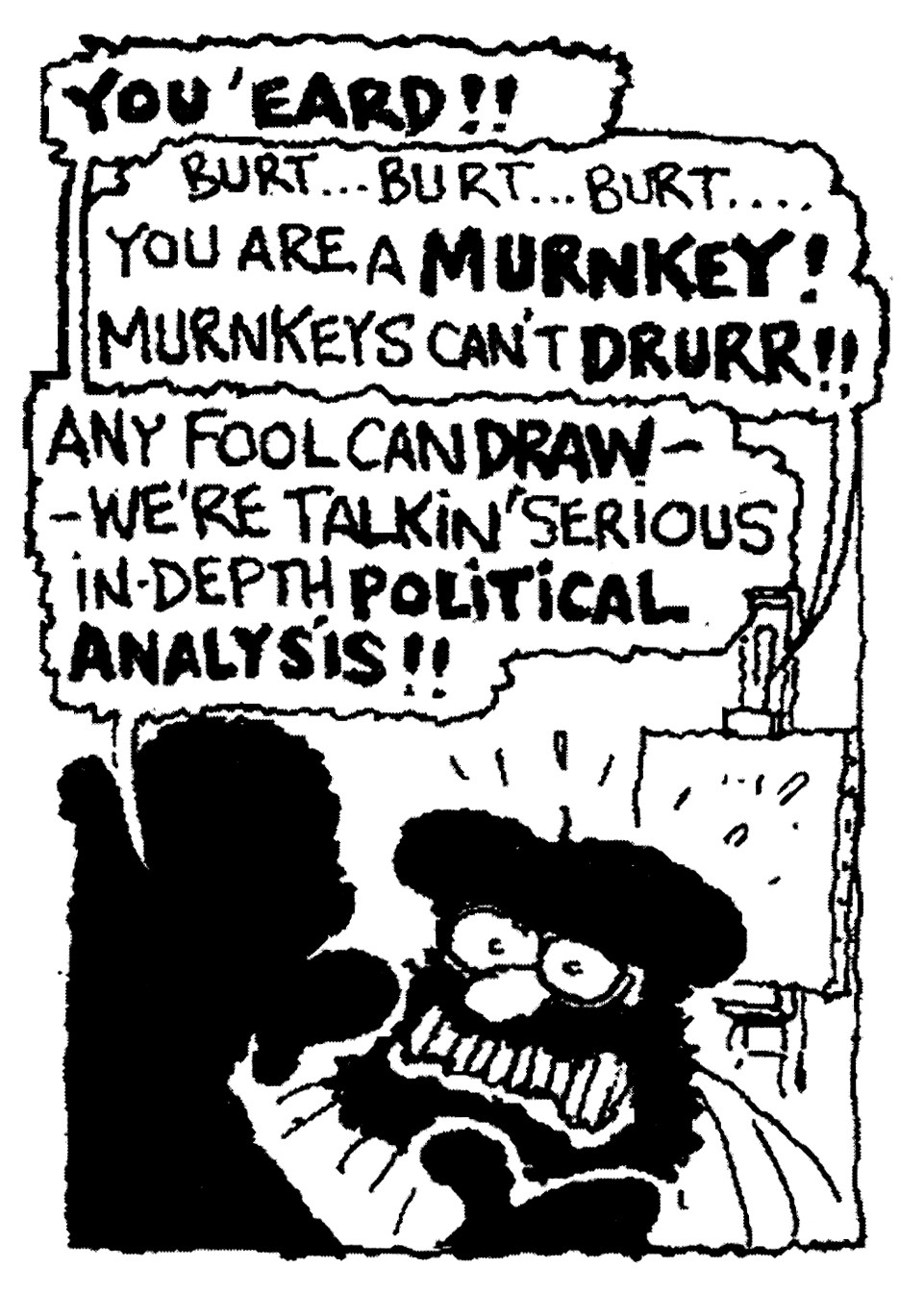

However, Bell had begun cartooning at Leeds, producing posters for the Film Society, and creating his alter ego ‘Monsieur L’Artiste’. In 1976, alongside his teaching, Bell also managed to do some unpaid work for the newly-launched alternative paper Birmingham Broadside, including a cartoon strip called ‘Maxwell the Mutant: Marauding the Midlands’, which he signed ‘S. Bell’.He secretly hankered to work for The Beano, whose cartoonist, Leo Baxendale, was a major influence on his work, but it was not to be – he carefully preserved The Beano’s rejection letter.

‘Maxwell the Mutant’ told the story of an ordinary man who gained the power to mutate intoother people, after drinkinga contaminated pint of mild in a pub called ‘The Whistling Pig.’ As Bell recalled, ‘his deadly adversary was Neville Worthyboss, a thinly veiled and rather inadequate caricature of the then Tory leader of Birmingham city council, Neville Bosworth.’ The strip’s success encouraged Bell to hand in his resignation in 1977, and to become a freelance cartoonist like his friend Kipper Williams. As Bell recalled, ‘I had no portfolio and no contacts, other than those Kipper gave me, and no plan.’

His first regular paid work was the short-lived ‘Dick Doobie the Back to Front Man’ for Whoopee! comic,which made twenty appearances from April to September 1978.In May 1979 his strip ‘Gremlins’, about a gang of misbehaving ink blots, began in the first issue of the comic Jackpot – alongside a strip by Norman Mansbridge. In the same year Margaret Thatcher became Prime Minister, and Bell learned from Duncan Campbell, the news editor of London’s Time Out magazine, that they were interested a political stripthat could attack the Conservative government. Keen to produce more political work, Bell began drawing ‘Maggie’s Farm’, aninspired political fantasy which was hugely successful, and later transferred to City Limits magazine. In 1980 Bell also began drawing the strip ‘Lord God Almighty’ for another left-wing magazine called The Leveller.

The driving force behind ‘Maggie’s farm’ was Bell’s intense dislike of Margaret Thatcher’s political beliefs and style of government. ‘I had this sense of total outrage right from the start because she was totally divisive,’ he acknowledges: ‘She was overthrowing everything I felt I believed in. If you were on the left in those days it was quite a bleak time because she swept in and changed politics to the way she wanted it.’ He saw her for the first time in October 1980, at the Conservative conference in Brighton, and confessed himself ‘horrified and intrigued.’ As he freely admits, during these years ‘I hated Thatcher and wanted her to die.’

Bell had already approached The Guardian and been turned down, but in 1981, with a mortgage and a family, he approached them again. He discovered that the paper was interested in a British strip cartoon which could run alongside Gary Trudeau’s ‘Doonesbury’. The Guardian’s design editor, Mike McNay, was a fan of ‘Maggie’s Farm’, and Bell was duly recruited to draw a daily strip for the paper called ‘If…’ The strip first appeared in The Guardian in November 1981, and Bell was given freedom to do what he wanted. ‘Evenat the earliest days I didn’t get any steer – do this do that’, he recalled: ‘I think the strip did take a few months before it established itself, and then with the Falklands Warit sort of took off – took on a life of its own.’

Steve Bell draws his cartoons to reproduction size and works on card or watercolour paper using John Heath’s Telephone Pen (Fine), brush and indian ink. The ‘If…’ strips were at first drawn in batches of six, and posted to London from Bell’s home in Brighton, or sent by train. But soon he was faxing them in, which enabled him to work to closer deadlines, usually the evening before publication. ‘I do my own editing’ he explained: ‘I don’t submit roughs to the paper. I couldn’t stand that – it would take years off my life…I decide what I’m going to do and do it. Generally it goes in.’

During the Falklands War, which broke out in April 1982, Guardian editor Peter Preston did refuse one of Bell’s ‘If…’ strips on grounds of taste, and there was another disagreement over a set of strips showing the Ayatollah and the Pope. As Bell admitted, ‘I dragged the Pope into it for no reason, and he (the editor, not the Pope) got stroppy about that’: ‘I didn’t want to change it, because there was nothing much I could change. What happened there was he just didn’t run them.’ In 1983 there were further problems when the Guardian was taken to the Press Council for Bell’s depiction of Henry Kissinger as a giant turkey with a German accent. In 1987 Bell’s ‘If…’ strip was characterised in the House of Lords, by a former Labour Foreign Secretary,as ‘a series of almost obscene lampoons on the President of the United States.’

‘I’m always coming up against the problem of taste and I freely admit, I do transgress,’ Bell told one interviewer: ‘I step over the line quite a lot but I think, well, you have to. It’s almost your duty to do it if you can.’ However, he admitted that the principal interventions in his Guardian work were small – ‘like a word change’: ‘I mean, I try to get fuck through…they always asterisk that one.’ One reason for the lack of intervention was that the Guardian editorial staff knew his importance to the paper – as did Bell himself. Peter Preston later recalled that conversations with him were ‘mostly laddishly jovial until they turn to money’, but an arrangement was reached that suited both sides. ‘I have a very free hand at The Guardian’, Bell acknowledged in 2009: ‘They don’t tell me what to do and I don’t tell them what I’m doing, I just do it and send it in.’

In 1990 Bell also began to work alongside Les Gibbard as the Guardian’s editorial and political cartoonist. John Major was elected Prime Minister in the same year, and Bell puzzled over how to represent him. While drawing him at Conservative Party conferences he had been fascinated by his upper lip – ‘he’s got what I can only describe as an ingrowing moustache’ – but eventually he devised a more enduring image of Major ‘as a crap Superman’, wearing his underpants over his trousers. After Bell’s caricature was well established, Alastair Campbell of the Daily Mirror revealed that the Prime Minister did actually tuck his shirt into his underpants – a sartorial gaffe that seemed to confirm the cartoon image. However, according to Major’s biographer, Anthony Seldon, the Prime Minister’s response to Bell’s caricature was that ‘it is intended to destabilise me and so I ignore it.’

Other politicians were less sanguine. In 1994 Bell, who had taken over from Les Gibbard as the Guardian’s political cartoonist,observed that ‘it’s not usually politicians who are bothered, but someone on the fringes of public life who is likely to sue.’ However, in June 1995 he drew a mock pieta with Margaret Thatcher as Mary and John Major with his head in her lap. Bell added Conservative Minister John Selwyn Gummer as the onlooker, and Gummer immediately wrote to the Guardian complaining that ‘to be forced to participate in Steve Bell’s perversions is degrading.’ Bell said afterwards that ‘I put Gummer in because he is a religious bullshitter…I have framed his letter like a commendation.’

Bell admitted that he ‘never really got Kinnock’, and Tony Blair ‘took a while’. He only developed his classic depiction of Blair after seeing him at the 1994 Labour Party Conference, when he made his first speech as leader. ‘I noticed he had a little mad eye of his very own’, Bell recalled, his right eye seeming to have a ‘psychotic glint’, while his left eye had a harder stare, giving a visual link to Margaret Thatcher.

By the time Labour won the 1997 General Election Bell hadperfected hislikeness of Blair. ‘He has sticky-out ears, receding hair, a flabby lower lip and those starry eyes,’ Bell noted soon afterwards: ‘That should be enough to be going on with.’ The Conservative Opposition proved less difficult. ‘Hague was easy!’ Bell recalled: ‘He came ready-made, an overgrown baby in schoolboy shorts. IDS [Iain Duncan Smith] was a joy too – too good to be true. Howard – I swore I’d never do that bugger again after Major’s government, but he was great. A vampire.’

Bell describes himself as ‘a socialistic anarchist and a libertarian’, and, though he rarely goes to The Guardian’s offices in London, still regards himself as a journalist.He sees cartooning as ‘an attacking medium’: ‘It’s not very good for saying positive things. You don’t attack someone you agree with.’ Blair’s Deputy Prime Minister, John Prescott, reportedly told a friend that if Bell came to the Labour Party conference he would head-butt him, but Bell takes that as a sign thathis work is succeeding. ‘You get a mild sense of disappointment when someone you are attacking says ‘ooh, I quite like that”, he admits: ‘You feel a sense of failure.’ The aim is to get beneath the surface: ‘Politicians put on a face, a mask, and you have to get under it.’ Bell admits that he was born cynical. ‘I have been lurking under the podium, drawing politicians so closely for so long, that I have almost come to like them’, he confessed in 2010: ‘These men and women are professional idealists and I take my hat off to them. Then I kick them up the arse.’

Bell has also contributed to Cheeky, Private Eye – including colour covers for Christmas issues from 1992, New Society, Leveller – the ‘Lord God Almighty’ strip, Social Work Today, NME, and the Journalist. He has contributed to the New Statesman, but in 1999 lost his job as cover illustrator after the deputy editor, Cristina Odone, told him she wanted ‘happy covers’. As Bell observed, ‘my cover depicting Tony Blair’s brain in a food-processor was dropped’: ‘Now I’ve been told that readers want politics with a small ‘p’ and cartoons must have bright and new colours.’ Bell has also made short animated films – with Bob Godfrey – for Channel 4 and BBC TV.He admires Beano cartoonist Leo Baxendale and David Low, but his all-time favourite cartoonist is Ronald Searle: ‘His draughtsmanship is wonderful and he’s very funny and astute.’

Cartooningis hard work,Bell argues, for ‘taking the piss is a business that demands considerable application.’ As he told one interviewer in 2001, it isn’t ‘an exalted art form’: ‘It’s lonely, low, scurrilous and rude. Its supposed to be.’ It is, he admitted in 2009, ‘a very solitary pursuit’:’You spend a great deal of time on your own, hunched over a drawing board, trying to think up jokes, trying to make yourself laugh.’ By that time he was producing eight cartoons a week for the Guardian, an outputwhich demanded four full days a week drawing at his home in Brighton and a fifth doing paperwork.As he admitted, it was ‘a horrendous amount of work, but…addictive.’ Bell was now scanning his finished cartoons and emailing the images to the paper, without any editorial intervention. As he admitted, ‘I never know what the editorial line is on anything’: ‘I never read the editorials, and I wouldn’t dream of trying to work out what they were.’

On 16 November 2012 the Guardian carried one of Bell’s cartoons showing Binyamin Netanyahu holding a press conference, with William Hague and Tony Blair as glove puppets. There were complaints that this cartoon embodied classic antisemitic iconography, and it was referred to the Press Complaints Commission as plainly antisemitic. Bell mounted a strong defence, arguing that It’s not antisemitic, it is focused on him as a politician, on his cynicism: It doesn’t generalise about a race, a religion or a people…it is a very specific cartoon about a very specific politician at a very specific and deadly dangerous moment. However, the Guardian published an editorial statement that the image of a puppeteer…inevitably echoes past antisemitic usage of such imagery, and argued that cartoonists should not use the language – including the visual language – of antisemitic stereotypes. Bell later said that this was a statement which I refute utterly.

As Martin Rowson wrote in 1994, ‘Bell is without doubt the finest political cartoonist working in this country’: ‘It’s not just that he’s almost unique among his peers occupying the leader pages of the nationals in coming from the Left, but also that he steadfastly pursues a personal political agenda often at variance with the editorials he rubs shoulders with. This is just what Low and Vicky used to do for Beaverbrook.’ ‘Steve Bell can stand shoulder to shoulder with any of his predecessors’, observed Nicholas Garland in 2005: ‘he creates a consistent parallel world – it is like ours, but full of strange creatures that can be machines or beasts or clouds and yet be politicians at the same time. And his work is always suffused with wild, even frightening, humour.’

Bell has a continuing faith in newspaper cartoons, observing in 2009 that ‘newspapers seem to be shrinking and reducing, and people say it’s a dying art form, and cartooning is an old-fashioned thing and maybe there’s no more need for it’: ‘I sort of feel differently. I think there’s more need for it, because the society we live in is so very visual, and visually driven. There’s a flood of images coming down the TV every day, and cartoons are a way of dealing with it…. I use that kind of imagery all the time…turning it over and twisting it in my own way.’

Holdings

1777 Uncatalogued originals plus photocopies (‘Maggies Farm’) ‘Lord God Almighty’ strip ‘If…’ [SB0001 – 2040] (1980s, 1990s, 2000)

Digital cartoons (1996-2020s)

References used in biography

- Steve Bell’s website and cartoon database at www.belltoons.co.uk [3] including autobiography at http://www.belltoons.co.uk/biography [4]

- Steve Bell’s video ‘sketchbook’ series for the Guardian – www.guardian.co.uk/world/series/steve-bell-s-sketchbook [5]

- Steve Bell video on the Iraq War – 10 years on http://www.theguardian.com/world/video/2013/mar/15/steve-bell-iraq-war-video [6]

- ‘Maggie’s farmer takes the penguin biscuit’, Guardian, 12 November 1983.

- ‘Cartoon Ruled Not Anti-Semitic’, Guardian, 7 December 1983.

- Hansard, House of Lords, 25 March 1987, Lord Stewart of Fulham speaking on Relations with United States and Soviet Union.

- Steve Bell ‘A Psychopath, a Mega-Nerd and now Bambi’, Guardian, 21 July 1994, p.22.

- CSCC Archive, John Harvey ‘Stiletto in the Ink: British Political Cartoons’, c.1994, pp.12-13.

- Martin Rowson ‘Funny peculiar, I’d say’, The Independent Sunday Review, 4 December 1994, p.42.

- ‘Disgusted of SW1’, Guardian, 15 June 1995, p.18.

- Steve Bell interviewed on 20 Jun 1995: http://web.archive.org/web/20000608225535/http://freespace.virgin.net/g.hurry/s_bell.htm [7]

- ‘Who’s Calling the Toon?’, Guardian Features, 4 January 1996.

- Simon Hoggart, ‘The Y-factor’, Punch 5-11 October 1996, p.12.

- Jack O’Sullivan ‘Can you recognise this man?’, Independent, 12 May 1997, p.6.

- Steve Bell ‘No Laughing Matter’, Guardian Media, 2 November 1998, p.3.

- Peter Preston, ‘His Nibs’, Guardian Unlimited, 1 May 1999.

- London Evening Standard, 26 February 1999, p.12.

- Alan Thompson ‘Saviour of Satire’, Sunday Herald, 19 September 1999, p.12.

- Mark Bryant Dictionary of Twentieth-Century British Cartoonists and Caricaturists (Ashgate, Aldershot, 2000), pp.20-21.

- Richard Marshall interviews Steve Bell and Martin Rowson, 3:AM Magazine, November 2001, at www.3ammagazine.com/litarchives/nov2001/bell_and_rowson_interview.html [8]

- Ollie Stone-Lee ‘Seriously Funny Work,’ BBC News Online, 5 November, 2001.

- Nicholas Garland ‘What makes cartoons great’, The Daily Telegraph, 15 February 2005, p.24.

- Guardian Unlimited, 7 December 2005, ‘Now for the difficult bit.’

- Will Henley The Art of Comedy: Steve Bell talks to SSP, Such Small Portions, 1 June 2007,

www.suchsmallportions.com/pg/news/suchsmallportions/read/473/the-art-of-comedy-steve-bell-talks-to-ssp [9] - Steven Vass Marching to his own toon, The Sunday Herald [Glasgow], 2 September 2007, p.78.

- Dave Harte ‘Steve Bell – The Birmingham Years’, 19 October 2008-daveharte.com/birmingham/steve-bell-the-birmingham-years/ [10]

- Anna Sussman Drawing the line between editorial and cartooning, Beirut Daily Star, 10 January 2009.

- Laura Davis The art of politics, Liverpool Daily Post, 15 May 2009, p.7.

- Steve Bell You must discover the character behind the face, The Guardian, 25 May 2011, G2 supplement pp.4-7.

- Jennifer Lipman ‘Antisemitic’ Guardian Gaza cartoon shows Jews as puppeteers, Jewish Chronicle, 16 November 2012.

- Chris Elliott The readers’ editor on¦ accusations of antisemitism against a political cartoon, The Guardian, 25 November 2012.

- Steve Bell on BBC Radio 4’s Today Programme, 29 January 2013 – http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-21241785 [11]