Martin Rowson

About

Martin Rowson was born in London on 15 February 1959, and is the adopted son of Dr K.E. Rowson, a virologist. Rowson began drawing as a small boy, copying Wally Fawkes’s cartoons of Edward Heath. He was educated at Merchant Taylor’s School and in 1978 went to Pembroke College, Cambridge, to read English. A self-taught artist, he began contributing cartoons and illustrations to Broadsheet whilst at Cambridge, and after graduating he published his first series of cartoons – “Scenes from the Lives of the Great Socialists” – in the New Statesman, where it ran from 1982 to 1983. It was later published as a book.

Rowson subsequently contributed to Financial Weekly from 1984 to 1989, and to Sunday Today from 1986 to 1987, and drew pocket and editorial cartoons for Today from 1986 to 1993. However, on Today his relationship with Rupert Murdoch’s editorial staff was not always smooth. “When I worked briefly as editorial cartoonist on Today,” he later recalled, “every rough for a cartoon I presented was rejected by David Montgomery as a matter of course, to keep me in my place with the rest of the hacks”: “It was clear that the maintenance of editorial terror was always more important than the contents of any cartoon.”

Rowson has also contributed to the Guardian (1987 to 1988 and editorial cartoons since 1994), Sunday Correspondent (caricatures and strips 1989 to 1990), Time Out (since 1990), Dublin Sunday Tribune (since 1991), Independent on Sunday (“Logorrhoea” strip since 1991 – renamed “Pantheon” 1994), Weekend Guardian (1991 to 1993), Independent Magazine (1993 to 1994), Tribune (political cartoons, covers, and “Blair’s Babies” strip since 1994), Daily Mirror (illustrations since 1996), Observer (financial cartoons 1996 to 1998), Daily Express (illustrations since 1998), The Scotsman (editorial cartoons since 1998), and the Times Educational Supplement (editorial cartoons since 1998).

Rowson’s style is visceral and deliberately offensive, and he sees himself as following in the tradition of the eighteenth-century satirists and cartoonists, such as Gillray. His resolute vulgarity has often brought complaints and resistance from editorial staff. In 1994, for example, Rowson provided an illustration for an article on yob culture in the Independent. It showed Michelangelo’s David farting, but the editor, Ian Hargreaves, felt in necessary to add a pair of Union Jack boxer shorts. In his own defence Rowson later recalled his contemporary response to the editor of Time Out, “when he complained about the amount of shit I was depicting to illustrate Tory sleaze: ‘If you can think of a better visual metaphor, kindly tell me what it is.'”

Even fellow cartoonists could be critical, and in 1997 Michael Heath attacked the new style of political cartooning that Rowson represented. “The whole thing’s a mess,” he said, “it’s cobblers”: “They say it’s going madly satirical. Rubbish. It’s just ugly. Worms coming out of John Major’s nose, that sort of thing. There’s no thought behind it.” As Rowson later observed, “I long ago worked out, from bitter experience amid the hate mail and death threats I’ve received from around the world, that while I see my work as a cartoonist as firmly in the tradition of William Hogarth and Gillray, everyone else sees it as breathtakingly vicious.”

Politicians have been equally critical. “What are the good things one can say about Martin?” commented Peter Mandelson at the opening of an exhibition of his work in June 1998: “Well, for one thing, he’s not Steve Bell”. A few days later Rowson’s Guardian cartoon of 13 July 1998 included a list of Mandelson’s platitudes, including “The Pope is Catholic…The Blairs shit in the woods.” One reader complained to his MP and to the Press Complaints Commission that this was a vulgar attack on the Blairs, and was “in extremely bad taste to say the least.” The Guardian made a half-hearted defence, saying that its cartoonists were “given as much freedom as possible and often tread a narrow path of acceptability”: “Their audience turns to them for this. This cartoon probably strayed over the boundary.”

Rowson likens his political cartooning to voodoo – “doing damage from a distance with a sharp instrument.” His portrayal of Tony Blair became increasingly unpleasant over time. “When I first started to draw Blair he was puppy-like,” Rowson acknowledged, “but he became more raddled with time. I used his teeth as a sort of political barometer.” As Rowson noted in 2012, the recurring figures in his cartoon commentary develop a symbolism of their own, and his cartoons “contain characters involved in an ongoing narrative – just because some of them bear a passing resemblance to real people is very often beside the point”.

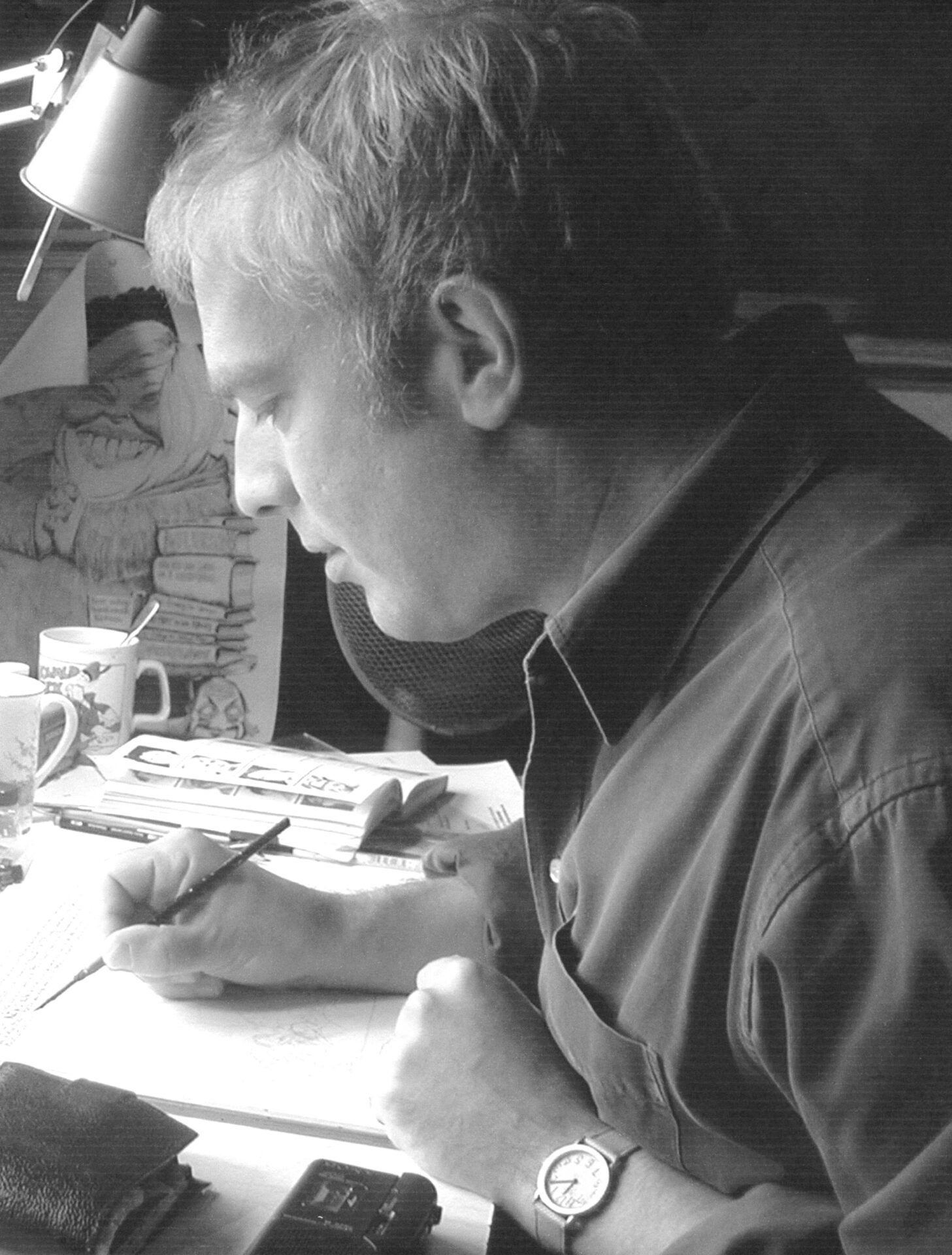

Rowson takes pride in the extent to which visual satirists can “get away with telling power that it’s stupid, it’s got a big nose and it should just bugger off.” He has no formal art training, but has never regretted it. “I don’t think of myself as any type of artist”, he noted in 2001: “I’m an artisan. I get crosser that we’re not taken seriously as journalists than I do that we’re not taken seriously as artists.” He regards himself as “a visual journalist”, and insists “that a leader page cartoon is more like a visual column than an illustration.” However, he delights in constantly learning new artistic skills. “Over the 20 years I’ve been doing it,” he told an interviewer in 2007, “I discover for myself new techniques every time I sit down to draw and find it really exciting.”

In April 2001 the Mayor of London, Ken Livingstone, appointed Rowson “Cartoonist Laureate for London”. “The last thing that politicians in this country can afford to do if they want to get re-elected is to admit they do not have a sense of humour,” Rowson commented, but added “I am glad there is a politician somewhere who is willing to allow a cartoonist inside the loop, however dangerous that could be.”

As Rowson admitted in 2001, “I’ve even had politicians phoning up and begging me to put them in a cartoon”: “There is nothing worse than a politician who never appears in a cartoon. Take Alan Milburn – I have never drawn him, mostly because I don’t know what he looks like, but also because I doubt very much whether my readers know what he looks like…and he can’t be happy about that.” Any appearance in a cartoon seemed better than none. “I’ve made people into toilets, pools of sick, pigs” Rowson observed in 2002: “What’s interesting is the way politicians react – they will quite often buy the cartoons as a way of defusing the magic, defusing the voodoo, taking back possession of themselves. I think they pretend they don’t mind, while cartoonists pretend they matter.”

Rowson considers the political cartoon to be “an oasis of anarchy in the topography of newspapers”, and is happy with controversy. After the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten published a series of cartoons of Muhammad in 2005, he produced a newspaper cartoon showing a bearded figure reading that issue of the paper and saying “It looks nothing like me.” This was not accepted for publication, however, and Rowson accepts that the internet “has changed things” for British cartoonists. Instead of addressing a single readership, they now “find their work being consumed, via the web, by people in nations who haven’t had more than 300 years of rude portrayals of the elite”:

When Steve Bell and I first had our cartoons for the Guardian published online, many Americans would recoil in horror at our depictions of their president. Steve and I got many emails pointing out that Bush was their head of state, deserved some respect, and then asked if we’d ever depict our royal family in the same disgraceful way. At that point, of course, you pull back the curtain on Gillray’s depictions of George III shitting on the French fleet…

Rowson has also worked as an occasional book reviewer for the Sunday Correspondent in 1989 and 1990, the Independent on Sunday (since 1990), and the Guardian, writes a column in Tribune and has been a council member of the Zoological Society of London since 1992. He is optimistic about the future for political cartoonists, although the newspaper cartoon may decline with the medium. As he explained in 2012, “we’ve been parasitizing on the back of newspapers, and when newspapers die, like any hideous sensible parasite, we’ll just jump off on to the next host.”

Holdings

2 Christmas card

1 unaccessioned original (Cartoonhub launch image)

3 ink sketches on acetate (used in lecture in December 1996)

1495 uncatalogued artwork

10 uncatalogued artwork

Digital artworks (2011-current)

References used in biography

- Evening Standard, 13 October 1994, p.31, “Rape and the Gettys.”

- John Windsor, “All Consuming; Good for a laugh”, Independent on Sunday, 10 May 1997, p.18.

- John Walsh “The New Bride of Frankenstein”, Independent, 6 July 1998, p.5.

- Mark Bryant Dictionary of Twentieth-Century British Cartoonists and Caricaturists (Ashgate, Aldershot, 2000), pp.193-4.

- Martin Rowson “Giants With No Honour”, The Times, 16 March 2001.

- Ian Mayes “The readers’ editor on… words that leave a bad taste in the mouth”, Guardian Saturday Pages, 21 April 2001, p.7.

- Brendan O’Neill “Me and my vote: Martin Rowson”, Spiked, 18 May 2001.

- Al Kington “Drawing on the power of cartoons”, Western Daily Press, 18 October 2001, p.26.

- Richard Marshall interviews Steve Bell and Martin Rowson, 3:AM Magazine, November 2001, at www.3ammagazine.com/litarchives/nov2001/bell_and_rowson_interview.html

- Lawrence Pollard “The Art of the Political Cartoonist”, BBC News Online, 18 August 2002.

- Michal Boncza and John Green “The truth told in jest”, Morning Star, 1 August 2007.

- Ali McConnell “Yankee doodles: Obama in cartoons”, 23 April 2009, news.bbc.co.uk/go/pr/fr/-/2/hi/americas/8004024.stm

- Martin Rowson “A rude awakening”, The New Review, 6 June 2010, p.35.

- New Humanist, July/August 2010, p.5, “Drawing a Line.”

- Helen Lewis “Ink-stained assassins”, New Statesman, 23 August 2012.

- Martin Rowson “Scarfe’s Netanyahu cartoon was offensive? That’s the point”, The Guardian, 29 January 2013.

- www.guardian.co.uk/discussion/user-comments/CartoonistRowson