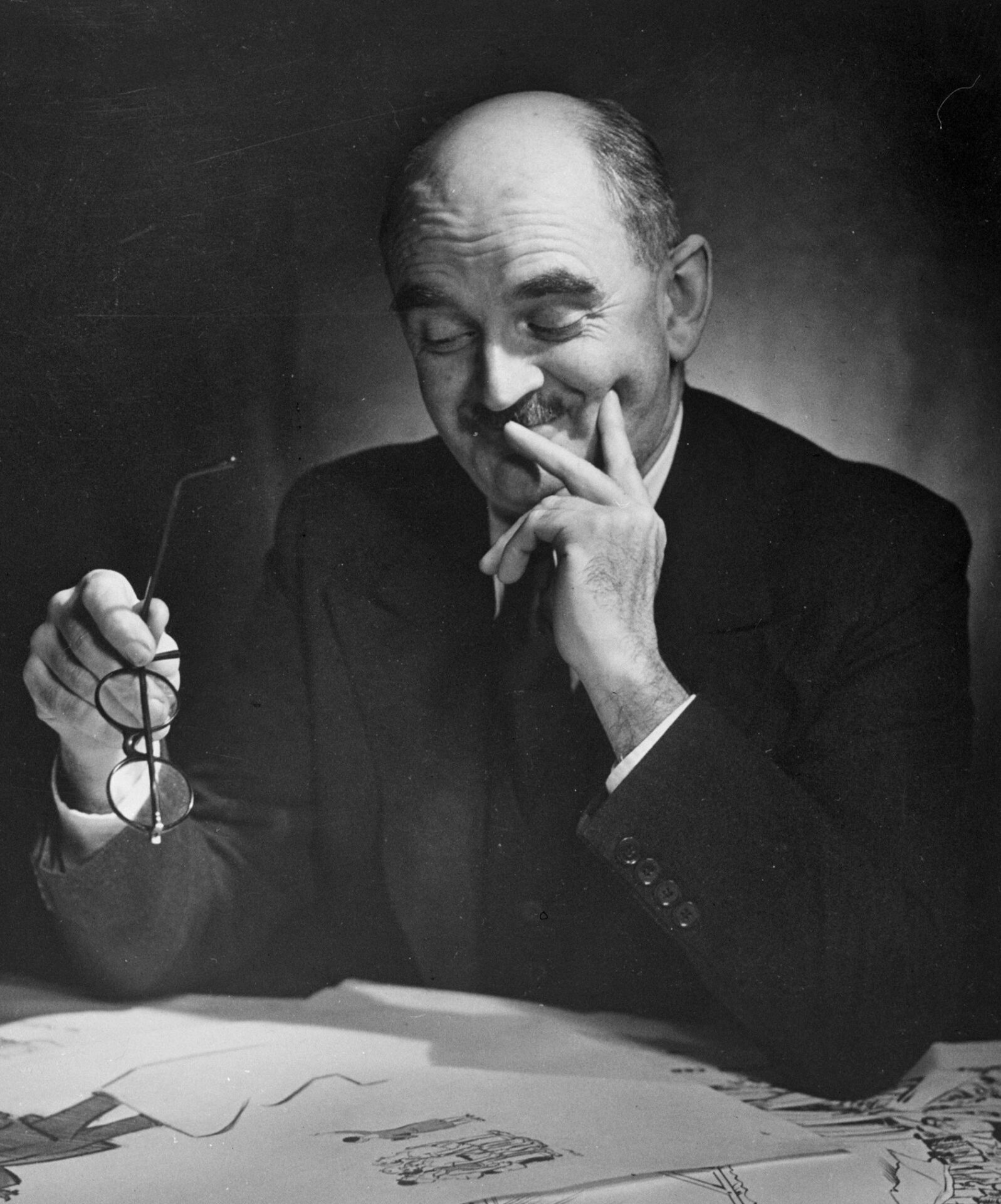

David Low

About

David Low was born in Dunedin, New Zealand on 7 April 1891, the son of David Brown Low, a Scottish-born journalist. He was educated at the Boys’ High School, Christchurch, and was attracted to caricature through reading English comics such as Chips, Comic Cuts, Larks and Ally Sloper’s Half Holiday. Early influences were also Punch artists such as Tom Browne, Keene, Sambourne and Phil May and caricaturists Gillray, Daumier and Philipon. Low was self-taught as a cartoonist, apart from a correspondence course with a New York school of caricature in about 1900, and a brief stay at Canterbury School of Art.

Low’s first strip was published in Big Budget at the age of eleven, and at the same time a topical cartoon was accepted by the Christchurch Spectator. He then began to win drawing competitions in the Australian magazine New Idea, and to contribute police-court drawings to New Zealand Truth. In 1907 he joined the Sketcher and in 1908 became the Spectator’s Political Cartoonist – his first full-time job. In 1910 he moved to the Canterbury Times, and from 1911 to 1919 worked for the Sydney Bulletin. At the Bulletin his technique benefited from the influence of Will Dyson and Norman Lindsay. His first cartoon to be published in Britain was a syndicated Sydney Bulletin drawing from 20 October 1914, which was reprinted in the Manchester Guardian on 4 January 1915.

In 1918 Low had great success with the publication of The Billy Book, which lampooned the Australian Prime Minister Billy Hughes. It became a bestseller and drew praise from Arnold Bennett, who wrote that “if the Press-lords of this country had any genuine imagination they would immediately begin to compete for the services of that cartoonist and get him to London on the next steamer.” Low did indeed leave for Britain, arriving in London in August 1919, and starting work for the Liberal evening paper the Star, in opposition to Percy Fearon (“Poy”) on the Conservative Evening News. He changed his signature from “Dave Low” to “Low”, and began pressing for extra space in the paper, which he got.

In 1922 and 1923 some of Low’s drawings were used on Liberal Party election posters. In 1924 Lord Beaverbrook invited Low to join his Conservative Evening Standard, but he refused. Beaverbrook repeated the offer in 1927, and this time Low accepted, becoming the paper’s first-ever political cartoonist, drawing four cartoons a week. The Standard had a smaller circulation than either the Star or the Evening News, but was a base from which his cartoons could be syndicated to a hundred and seventy journals worldwide. Despite warnings from friends, Low managed to forge a working relationship with Beaverbrook, who did not share Low’s political outlook but respected his ability and his circulation value.

During the 1930s Low was a fierce opponent of Hitler, and Mussolini, and of the policy of Appeasement. Perhaps his most famous cartoon creation, “Colonel Blimp”, first appeared in the Evening Standard in April 1934, and continued to make confused and childlike pronouncements on current events. “With the sympathy of genius”, wrote The Times in 1939, “Low made his Colonel Blimp not only a figure of fun, the epitome of pudding-headed diehardness, but also a decent old boy.” Low also contributed to Picture Post, Ken (large double-page cartoons), Graphic, Life, New Statesman (of which he later became a director), Punch, Illustrated, Colliers, Nash’s Magazine, and Pall Mall Magazine – in which the satirical ‘The Modern Rake’s Progress’, based on Edward VIII, had first appeared in September 1934.

Low’s work was now in the Tate Gallery, and his waxwork was in Madame Tussaud’s. He helped to create the reputations of those he cartooned. “In general,” he told one interviewer in 1942, “politicians like to figure in caricatures and cartoons”: “We help to ‘build up’ their personalities…Sir Austen Chamberlain asked me once, when he was posing for me, ‘Need I wear my monocle? I can’t see with it very well.’ ” At the height of his powers, Low was offered a knighthood, but turned it down.

In 1948 Low’s Evening Standard cartoons were cut from four columns to three, and at the end of 1949 he resigned from the paper. He was invited by the Editor of the pro-Labour Daily Herald, Percy Cudlipp, to succeed the cartoonist George Whitelaw, and began work in February 1950. The contract was for Low to draw three cartoons a week for £10,000 a year – the same salary he had been getting on the Evening Standard. Low’s old job was offered to Gordon Minhinnick, political cartoonist on the New Zealand Herald, but he turned it down. However, Low did not really settle at the Daily Herald, and moved to the Manchester Guardian in February 1953. The paper had previously used syndicated cartoons, including some of Low’s, but he became its first staff cartoonist.

Low continued to work at the Guardian until shortly before his death. He was still highly regarded, but Ralph Steadman, who met him in 1957, recalled later that he “was my bete noir”: “Something turned me off him as the voice of authority…He was the insider playing the maverick, hand-in-glove with Lord Beaverbrook.” In 1958 Low received an honorary doctorate from the University of New Brunswick, receiving similar honours from Canada in the same year, and from Leicester in 1961. In 1962 he was finally knighted.

Low was perhaps the most influential political cartoonist and caricaturist of the twentieth century – he produced over 14,000 drawings in a career spanning fifty years and was syndicated worldwide to more than 200 newspapers and magazines. He also created a number of memorable comic characters, including the walrus-moustached Colonel Blimp, the TUC carthorse, and the Coalition Ass. He drew in pencil for two famous series of political and literary caricatures published by the New Statesman in the 1920s and 30s, but otherwise worked mainly in ink using a pen and brush.

While at the Standard he worked from his studio in Hampstead and did not submit roughs but drew a single very detailed pencil sketch which he would then transfer to a clean sheet, spending five to eight hours on the finished drawing which would be collected by the paper at 5.30 pm each day. When James Friell (“Gabriel”) went to the Evening Standard in 1956, David Low advised him not to work at the office: “‘You don’t want to get too friendly with editors,’ he said, with that twinkle in his eye. ‘Gives them ideas above their station.'”

A member of the Savage Club and the National Liberal Club, Low always regarded himself as “a nuisance dedicated to sanity”. He died on 19 September 1963.

Holdings

- 2 boxes Low cuttings, 1938 – 45

- Low to Martin letter Drawer M

- 58 originalsDLNZ0001-DLNZ0058

- 1 catalogued original DL3151

- 1 catalogued print DL3150

- 1 catalogued artwork DL3152

- 3 catalogued originals Giles Collection GAX00098-100

- 4 photographs of Low and family

- Small sketchbook

- Wax hands

- 32 prints (plus duplicates) published in New Statesman

References used in biography

- Percy V. Bradshaw They Make Us Smile (London, 1942), p.65.

- James Friell “Time to Talk”, BBC Radio 4, 8 November 1968.

- Colin Seymour-Ure and Jim Schoff, David Low (1985)

- Mark Bryant (ed.), The Complete Colonel Blimp (1991)

- Les Gibbard “Gordon Minhinnick: Art of Rude Noises”, The Guardian, 18 March 1992, p.39.

- Ralph Steadman “The pen is mightier than the word”, Observer, 27 February 2000, p.6.

- A digital version of David Low’s autobiography is online at www.archive.org/details/lowsautobiograph017633mbp

Image: Yousuf Karsh – [1] Dutch National Archives, The Hague, Fotocollectie Algemeen Nederlands Persbureau (ANEFO), 1945-1989 bekijk toegang 2.24.01.04 Bestanddeelnummer 902-2079, CC BY-SA 3.0 nl, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=37129837