The FEW meter_ Bogotá

Featured stories

Case studies

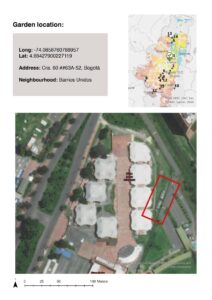

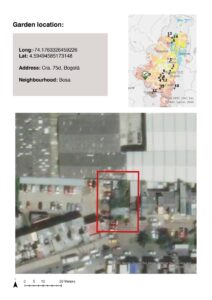

G. started his hydroponic garden in 2018, after being involved for many years in community garden programs around the city. He recalls the hardships of managing urban gardens in public areas as they can get vandalised, hence he is very satisfied with his current garden arrangement, as it is located in the premises of “Plaza de los artesanos”, a multipurpose venue hosting the local artisan market, which guarantees him exposure, access to water, and safety. This venue is located in the district of Barrios Unidos, characterised by a medium-high social stratum index (3 and 4), nearing some of Bogotá’s most renown parks (such as the Bogotá Botanical Garden, the metropolitan Park Simón Bolívar, the “El Salitre mágico” amusement park, the park of “Los Novios”). These parks create a green citadel covering an area of 5 square kilometres, with heavily trafficked boulevards cutting through it. Given the monumental scale of these spaces, people mostly reach them by car or public transport. The premises of Plaza de los artesanos are delimited by perimetral fencing and access is granted only upon identification at the checkpoint gate. These security features, which may seem strict to a western observer, are quite the norm for Bogotá. The venue consists of several buildings and a huge, covered square, all built employing the typical “ladrillo”, a recurring feature in Bogotá’s facades. This facility is employed to host big scale temporary or permanent events.

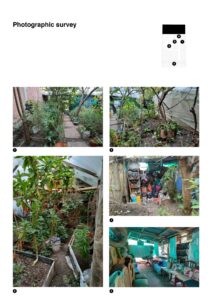

The hydroponic garden is located in the green space behind one of the wings of the covered square, next to flowerbeds and other fenced gardens. The garden is installed under three canopies covering a total of 250 square meters. Two canopies, equal in size, host two pairs of “A” frames, each supporting 22 PVC tubes. Each tube is six metres long and can host up to 33 plants. The two structures are served by 3x 500 L water tanks, which are filled periodically through the venue’s water system. The plants in these two structures are watered through the Nutrient Film Technique (NFT) method, whereby plants are irrigated by a constant flux of enriched water circulated through the tubes. In an adjacent tent G. also grows edible mushrooms through aeroponics, another soil-less technique which requires plants to be fed by water vapor. Through this method, he can grow a good amount of lettuce, onions, basil, and mushrooms, which he sells to direct buyers or in the nearby market. He is willing to keep the prices low so that his business gains momentum. His main clients are nearby restaurant and bars who discovered his garden thanks to its proximity to the event centre.

This garden also fulfils a social purpose, as G. committed himself to employ two collaborators with physical impairment; moreover, he regularly trains volunteers and receives visitors who want to learn about soil-less techniques. This garden regularly collaborates with the nearby Botanical Garden for educational workshops and weekly markets.

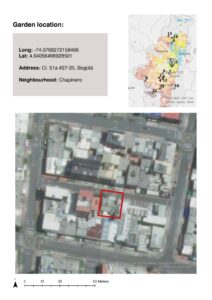

Huerta Mundo Verde Corazón Verde is a terrace garden of approximately 30 sqm located in the district of Teusaquillo. This district has a high social stratum index (predominantly 4), has a mixed land use and medium density. Its built environment is characterised by residential areas alternating with a mixture of neighbourhood shops, bars and clubs. The layout and moderate size of its streets make this area, which is quite central and well served by public transport, easy to walk. The buildings have a modern and well-kept appearance. Some of them are separated from the street by tall metal fences, while their façades are often framed by an intricate network of electric cables.

C. is a building administrator who was tired of looking at grey Eternit roofing from her terrace. It is for this reason that she decided to start growing plants on her rooftop with the aim of bringing back pollinators and birds in this area of the city. The L-shaped space is covered with containers of various designs and sizes, many of them from reused waste, resulting in a total of twenty-five raised beds in the open-air terrace and the self-built greenhouse. C. remarks that one of the most important aspects for a successful harvest is sun exposure and add that the highland equatorial climate that characterises Bogotá guarantees a constant supply of rainwater alternating with good sun exposure and moderate temperatures; it is intuitive how this factor works in favour of urban farmers, who may sometimes not have the means or time to irrigate their gardens on an ongoing basis.

Irrigation is done through rainwater harvesting, whereby the water gets collected and filtered in a tank in the communal ground floor garden from where it gets reconveyed to the terrace through an electric pump. C. is helped by an architect and a designer who assisted her in the construction of canopies, greenhouses, raised beds and the irrigation system of this garden. The two met C. during an urban farming event in a nearby park and were invited to join her activity. Although this vegetable garden is attended by two people from outside C.’s household, it is still classifiable as a home garden since it is located on the roof of her house. It is always C. who provides access to her two friends and the food produced within this space goes to her family. This condition may change soon as this space, started as a small recreational family activity, is currently gearing up to become part of the network of educational gardens in the area and has to its credit two workshops. The hybrid features displayed by this and other case studies may be linked to the informal nature (even in formal urban contexts) of urban farming.

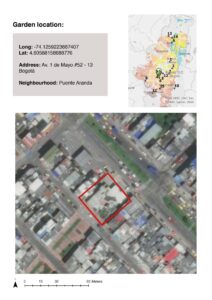

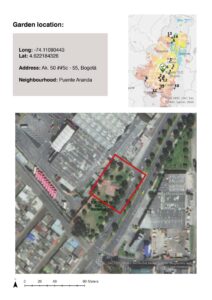

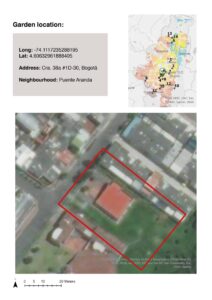

This garden is a workshop on the rooftop of the building for the Junta de Accion Comunal (JAC) of the Barrio of Sant Eusebio. The garden was founded in 2016 and serves to educate the community on urban agriculture, food harvesting and promote sustainable lifestyles. The organization and lessons of this classroom are managed by I. and D., who coordinate various urban agriculture projects in Puente Aranda.

The Puente Aranda district is located in the central part of Bogotá and is characterised by a medium social stratum (3). The industrial origins of this district emerge in its layout, where specialised commercial blocks are separated by medium-income residential areas by large road arteries marked by the monumental Transmilenio stations, the local Bus Rapid Transit system (BRT). Although there are several neighbourhood parks, these seem to be residual spaces between buildings, rather than the result of conscious urban planning. The JAC in the San Eusebio district is a small concrete building on one of the area’s busiest streets, Avenida 1° de Mayo. The building is flanked by a number of petrol stations and car washes and has a run-down appearance. To enter it, it is necessary to open a heavy gate that prevents unauthorised access. Once inside, a concrete staircase at the side of a lightwell leads to the flat roof of this one-storey building, part of which is occupied by the educational garden.

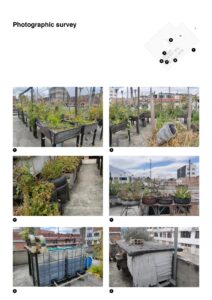

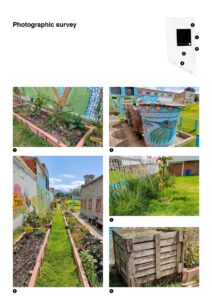

This open-air classroom of only 24 square metres consists of a series of containers arranged in several rows with regular intervals between them. In this way, all sides of each planter can be accessed, thus allowing up to four people to interact with each container. Furthermore, movable raised beds are employed to accommodate the needs of its older participants.

The garden features 24 raised beds (0.8×0.8 m), 5 larger raised beds (1×1.2m), 3 smaller raised beds (0.6×0.6 m), 6 tyre vases (0.6 m diameter), and 2x 1 m3 water tanks used for aquaponics. The whole area is covered by a canopy of 5×10 meters. All the equipment of this garden comes from repurposed materials.

This organisation is committed to promote more sustainable livelihoods through the teaching of organic agriculture and recycling. The organisers also manifested their interest in changing the common perception about local varieties of plants that are commonly regarded as basic staple for the lowest strata of the population by educating people about their use. The food produced for demonstrative purposes by this garden, which has one of the highest yields among the case studies, is either distributed between the participants to the workshops or consumed by the garden managers.

In spite of this garden being acknowledged by the local authorities and supported by the Botanical Garden in many of its activities, it was recently given an eviction notice and is currently relocating. This constitutes a temporary setback for a garden that should not be considered in its individuality, but as part of a rhizomic network of initiatives, places and individuals, promoting alternative lifestyles in the district. In fact, this garden liaised with ten other community and educational gardens in the Puente Aranda area with the aim of creating a network of actors, called “HuertoCircuitos”, pursuing an agenda of socio-environmental reconnection through artistic, cultural, and gastronomic initiatives.

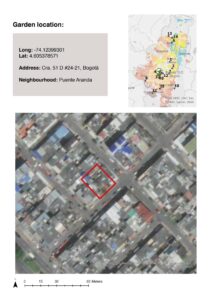

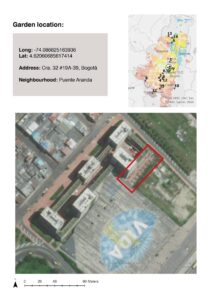

Huerta Enverdesiendo is a home garden run by D. and I., a high school professor and a zootechnician, who are also the managers of several urban agriculture initiatives within the Puente Aranda area, with CS3 being one of them.

As mentioned for CS3_ Junta de Accion Comunal San Eusebio, the district of Puente Aranda alternates industrial and commercial spaces with residential constructions of medium extraction, where green spaces seem to be in short supply. The house of D. and I. is not far from the JAC San Eusebio and is located on a side street of Avenida 1° de Mayo. The street front is a mix of neighbourhood shops, car washes and private houses. Their height varies from two to three storeys above ground and their entrances are often protected by gates that take up their entire façade. The façades of the buildings are constructed with good materials but have no particular aesthetic qualities. The most commonly used materials are bricks, cement and tiles. Urban greenery is scarce, apart from a few flowerbeds found at the edge of pavements.

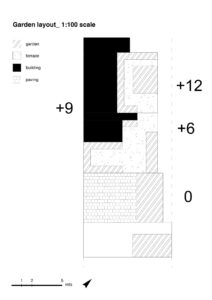

The house of D. and I. is an exception in this sense, as its entire façade is framed by ornamental plants, vines, and trees. Throughout the years, the couple has converted several hard surfaces of their family home into productive spaces through raised beds, in-soil agriculture, and pottery.

At the street level two in-soil allotments can be found: one within the premises of the property, where several types of edible plants are grown, the other on the adjacent sidewalk, where decorative plants can be found. Reaching the top floor of the house we find a first terrace garden that features pottery and raised beds, various types of edible and ornamental plants, an aquaponic fishpond and a container where vermiculture is practiced. The top roof hosts raised beds, a composter, a water tank that is refilled through the city’s supply network, together with several beehives.

The farming skills and dedication to the cause of sustainability of both I. and D. allow this small home garden to attain great yields. The food produced in this garden is for self-consumption. It is worth noting that the presence of beehives on the rooftop of the property certainly favours the pollination and growth of the plants of this garden. Lastly, this home garden is also the official headquarters of the “Fundacion Biosferas”, an organisation funded by the couple with the aim of creating strategies for the participation and integration of the community around proposals for collaborative social pedagogy on environmental issues. “Fundacion Biosferas” is involved in the “HuertoCircuitos” network mentioned in CS3,4,7,8,12.

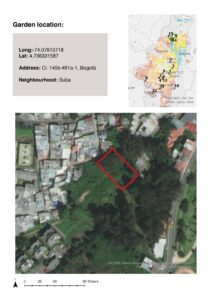

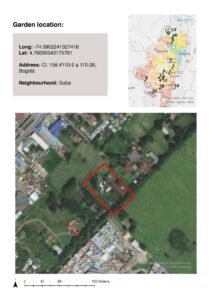

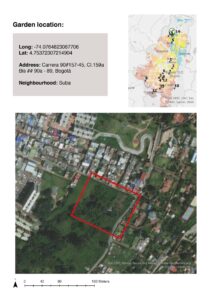

Huerta San Francisco was founded in 2019 thanks to the support program of the Botanical Garden, after a group of neighbours asked for a training on the topic of food sovereignty. The community garden “La Huerta de mi barrio-parque San Francisco” serves as a collective open air learning experience for the whole neighbourhood. This community garden is located next to a playground in a neighbourhood park, which acts as an edge between a low stratum neighbourhood and an affluent one in the district of Suba.

The district of Suba expands towards the rural areas northwest of Bogotá and is characterised by a diverse built environment ranging from semi-informal settlements (Social Stratum Index 2) to affluent estates (Social Stratum Index 6). To get to CS5, we walk towards the Suba hill from the “21 Ángeles” Transmilenio BRT station, crossing an area of prestigious residential buildings protected by guarded fences, with neat façades in “ladrillo”, a type of brick characteristic of the Bogotá area. Halfway up the hill the built environment changes abruptly, the houses become small and made of raw materials, the bricks used are no longer finely crafted, but those that are commonly seen in informal settlements across Latin America; the dwellings can be directly accessed by the street. The clashing aesthetics of this neighbourhood are likely due to an ongoing process of gentrification, triggered by the construction of the BRT station which increased the property value of these once peripheral areas.

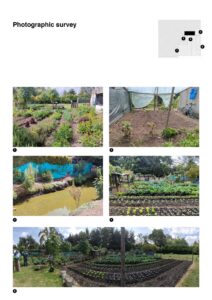

Taking a side street where luxury buildings face small, modest houses, we arrive at San Francisco Park, a green pocket on the side of the hill. The park is well maintained and features a playground, several benches and a pathway that runs around its perimeter. Alongside this path we find “Huerta de mi barrio”, which includes five flowerbeds identified by signposts, along with a dozen composting mounts.

A community of neighbours, made up by families and individuals of various age and gender, meets here on a weekly basis to take care of the plants, attend workshops, or collect food waste to produce compost. It is worth noting that although this space is not particularly productive in terms of food, which is distributed among participants, it has a tremendous impact on the lifestyle of an entire neighbourhood, as its members often replicate in their home gardens the sustainable farming practices they learnt together in this community garden.

Although the yield of this space may be low from a conventional standpoint, this garden is highly productive with regards to food waste recycling, which is attained through the use of the “paca digestora Silva” method. This methodology allows to produce big amounts of compost with low effort through the compacting of layers of kitchen scraps and dry offcuts in a cubic mould of 1 meter side. The community is very active in this sense and, by bringing food waste from their kitchens and processing it on-site, has made a dozen blocks of compost thanks to this method.

“Huerta la Libelula” is a community garden located in a public park in the Puente Aranda neighbourhood. The mainly industrial character of the Puente Aranda district (already described in CS3 and CS4) is particularly evident in the case of this garden, which is located near the “Distrito Grafiti”, an area of commercial warehouses. Thanks to the support of the municipality, this block, consisting of tall hangars with a hostile and unattractive appearance, has been transformed into an open-air gallery for street-art. The use of murals to beautify the built environment while conveying socio-political messages is common in all the urban districts of Bogotá, regardless of their social stratum. The municipality welcomes this type of manifestation, which is seen as a way to democratise art, regenerate problematic areas, and stimulate tourism.

Socio-political engagement and spatial upgrading are two themes that we also find in this garden, created in 2020 after a youth collective decided to recover the local park, which was at the time used for illegal dumping and squatting. The park is located on the side of the heavily trafficked avenue Avenida Carrera 50 and features a skate park and a playground.

Following their motto “Desde las raices Puente Aranda Renace” (From its roots Puente Aranda is reborn) this group of activists progressively cleaned out the area and begun experimenting with urban agriculture. At present, the site is composed of several circular plots where the main produce is herbs (aromaticas), two areas with vermiculture and compost beds (paca digestoras). Several signs display the varieties of plants harvested, along with politically motivated messages (such as ‘the land belongs to those who cultivate it’ or ‘re-evolution’) and references to the local ancestral culture. Watering is done manually through a small tank that the gardeners re-fill at a carwash nearby; in some cases, the community members water the plants with water they carried from home; rainwater is also a source of irrigation, however it is not stored (hence cannot be measured).

There is no security in place for the garden, nevertheless it remains in good conditions and the manager noticed that on some occasions people planted something after they harvested under no supervision (as in the case of the avocado trees that were planted by passers-by). This garden does not seem to contribute in a significant way to the sustainment of gardeners and locals as the quantities harvested are too small. Interestingly, although aromatic herbs were observed during on-field measurements, these were not reported in the farmers’ diary. This may suggest that, for this garden, aromaticas only fulfil an aesthetic or symbolic function.

While food production is not a priority for this garden, this space provides an opportunity for people to socialise. This is confirmed by the garden manager, who mentioned that this neighbourhood has been subject to great immigration fluxes and people are looking for a way to create a community. Immigrants’ newfound sense of belonging to a community and children’s environmental education are among the contributions of this space to the social cohesion of the neighbourhood.

The “Plaza de la Hoja” social housing intervention, inaugurated in 2015, wanted to tackle the housing deficit in the city centre for rural migrants who, as we have seen, are often relegated to the outskirts of Bogotá. The original project envisaged a series of residential buildings complemented by multifunctional spaces to make this intervention accessible to the public: a community development centre, a cultural centre, a kindergarten, commercial spaces, an office tower and a public square. However, the project was not completed according to plan by the sponsoring public institutions, who decided to build only the residential blocks and a kindergarten. Due to security concerns, the permeable parts were fenced, thus undermining the effectiveness of the commercial spaces that are now abandoned. To date, this uncompleted social intervention is considered one of the ugliest and most dangerous places in Bogotá.

The collective garden “Hojas de Esperanza” was started in 2015 on the rooftops of the residential blocks of Plaza de la Hoja by some residents who wanted to improve their community while preserving their cultural heritage. Unfortunately, the garden had to be closed as the roof was not fitted to host plants which, when irrigated, caused leakages. The idea of a collective garden was taken up again at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic when some residents felt the need to increase their food security. The long strip of land that runs along one side of the perimetral building fence, nearby the communal parking inside the residential complex, was chosen for this purpose.

Terracing was necessary to optimally use this space, where dirt and debris had been piled up during the construction works. The garden is managed by 4/5 volunteers and the food produced is shared among the residents of the estate (1kg per family). Watering is done through rainwater harvesting tanks placed on the highest level of the terracing and, occasionally, with water from the establishment during the dry season. The garden serves as a complementary support to the inhabitants’ diets and has become the catalyst for initiatives on environmental awareness and recycling. In particular, the garden is very active in composting food waste through the “paca digestora Silva” method. This composting method, which has already been illustrated for CS5 and CS6, is being practiced outside of the premises of the building, in an adjacent unsupervised area that the garden managers have reclaimed for the purpose. This garden also takes part to the garden network of Puente Aranda HuertoCircuitos (see CS3,4,8,12)

Although this garden has a social agenda, it was classified as home garden since the activities that mainly take place on its premises entail solely food production, with few people taking part in them. Albeit this classification was necessary for the apprisal of the impact of urban agriculture on Bogotá at the city scale, we are aware that some gardens have hybrid features that make them fall into a gray area. What clearly emerged from this exercise is that urban gardens in Bogotá often fulfil hybrid functions while pursuing everchanging agendas.

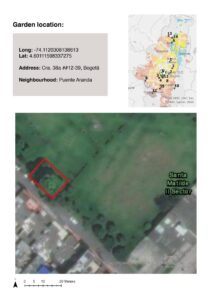

“Huerta Santa Matilde” was founded in 2021 by a group of neighbours who wanted to re-claim the public space in the eponymous park located in the southern part of the Puente Aranda district. This part of the district is mainly composed of residential buildings with a medium Social Stratum Index (3) and shops (see the case studies 3,4,6,7 for further details).

Santa Matilde Park stands on a brownfield that was put up for sale as construction site in 2021 by the private company that owned it. Residents have mobilised to prevent this space from being destroyed, as it has been a meeting and recreational place for the community for more than 60 years. The park has a surface area of 5,800 square metres and is surrounded by trees on its perimeter, while featuring a football pitch and some paths provided with night lighting. By creating the Santa Matilde urban garden, the local community wanted to manifest its presence within the park. This gesture is particularly significant as it shows how, in an area lacking green spaces such as Puente Aranda, citizens are mobilising to have their environmental rights recognised.

The community garden is located on the southern corner of the park and consists of a small plot of 6 by 4.1 m cultivated with edible vegetables as well as aromatic herbs, surrounded by several micro-interventions, such as individual plants and “pacas digestoras”.

Despite its contained dimensions, this garden is very active within the network of urban gardens “HuertoCircuitos”, coordinated by the organization “Fundacion Biosferas”. The network often organizes collective activities, such as training workshops and exchange trips between gardens. This space aims at strengthening the cohesion of the local community, while generating sensitivity towards environmental issues such as sustainability and self-production.

Although food production is a secondary concern for this garden, its produce gets divided among its participants. This part of the Puente Aranda district is relatively safe, yet it is worth noting how this community garden has been established near a police checkpoint and its managers monitor it through vigilance cameras that are part of the neighbourhood watch program.

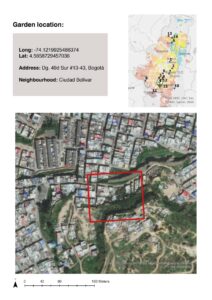

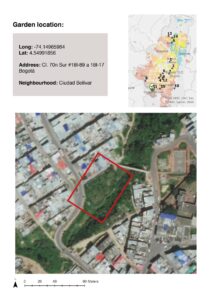

The La Estancia district of Ciudad Bolívar is located in the southwest of Bogotá’s urban territory, on its border with the province of Cundinamarca. The Autopista Sur, the multi-lane highway from which freight trucks enter the city, is the main road axis in this area that divides the District of Bosa from that of Ciudad Bolívar. This area is characterised by a low Social Stratum Index (1 and 2), with low-cost social housing blocks towered by the informal settlements spreading on the steep hills behind them. Buildings are modest or run-down in appearance, and air quality is poor, given the proximity of the major road artery. The green spaces of this area have been completely absorbed by the uncontrolled expansion of informal settlements.

The educational garden “PIWAM_alimentos para la vida”, located at the side of a carwash in a street near the Portal del Sur Trasimeno bus station, was created in 2012 by an old lady who wanted to strengthen the bonds within her community using urban agriculture. The garden has subsequently been taken up by various managers and is currently run by D., who is helped by his fiancée and an elderly lady.

The garden is delimited by a high fence and accessible through a gate guarded by the employees of the neighbouring carwash. It is composed by various areas that fulfil different functions: after passing the gate, we come across a workshop space equipped with chairs and tables; through this area it is possible to access an open-air garden, which in turn contains a green house, a composting area, a vermiculture tank, a recycling area (which is not currently being used), and a food waste recycling system (consisting of stacked filtering buckets). Water is supplied by the neighbouring carwash, while little or no electrical power is being used, similarly to what happens in the rest of the case studies.

The commitment of the community to this garden varies over time, which explains its fluctuating productivity. In April 2022, D. collaborated with the local university Uniminuto by running educational workshops with students on a weekly basis. This space has both educational and productive purposes (for self-consumption) and is one of the few that sells ams and sauces, albeit very little revenue is generated.

This garden has also created a seed bank to maximise its productivity and emancipate itself from seed trading companies. D. decided to take action after noticing that the seeds purchased at the local markets generated plants that could not easily survive in the urban context. If the plants survived, they would often produce sterile seeds. D. attributes this to a specific strategy employed by seed trading corporations to maintain their monopoly on the market and keep the demand for their products high. To tackle this issue, D. systematically crossed plants grown from market-purchased seeds that would adapt well to the urban context, while maintaining a good reproductive rate.

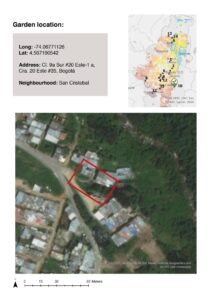

The “Altofucha” area is situated within the district of San Cristobal, southeast of the urban territory of Bogotá, and identifies the upper part of the Fucha river (Muisca word for dancing girl), which flows from the Andes towards the city. Although this area is only two kilometres away from the city centre, the steepness of the Andes has halted Bogotá’s expansion in this direction. That is why Altofucha, as well as the entire area east of Bogotá, has retained most of its natural heritage.

The steepness of this area prompted the municipality to declare many of its territories as Non-Mitigable High Risk for construction. The territories were to become “Protection Soils” thus fulfilling environmental functions. In doing so, however, the municipality ignored the rights of the informal settlers who already lived in the territory. J. and her parents moved in the Altofucha area in the neighbourhood of Laureles around 30 years ago, after their bought their plot from who they thought to be the legal owners of the land. This proved not to be true and they, like many others, were considered illegal squatters that invaded the border of the city, despite having purchased their land.

The Laureles neighbourhood has a strong rural character, sprawling along the steep green slopes of the Fucha river basin. The houses were all self-built by the inhabitants and display the classic features encountered in the informal settlements of Bogotá, such as un-plastered brick and cement façades, sheet metal roofs, and partially paved streets. The supply of water and electricity is guaranteed throughout the area and road improvements are currently underway. The settlement is connected to the city centre through a shuttle service, which is judged inefficient by the inhabitants.

The inhabitants of the settlement cherish their rural lifestyle and feel deeply connected with the natural entities of the Altofucha reserve, which they pledged to protect.

There are three parties that are currently disputing over this territory: firstly, the city council, who claims that J.’s community is invading a natural reserve; secondly, the “illegal” community of settlers; thirdly, the developers who were officially authorised to build luxury apartments up to 12 floors of height in the same area where the community of Altofucha currently resides. This reveals the different attitude of the municipality towards stakeholders with different purchasing power.

In spite of these hardships, J.’s community decided to reclaim its role as guardian of the Altofucha reserve; this was the premise that led to the creation of the collective “Huertopía”, a group of residents who practices urban agriculture to sustain themselves and strengthen their community through the sharing of traditional knowledge, youth education activities and the pursuit of an eco-friendly lifestyle. The garden where this collective was born is located between a retaining wall and J.’s house. It has a triangular footprint and features several flowerbeds made of “guadua”, a local type of bamboo. Urban agriculture seems to be at times a pretext for this community to gather and consolidate itself through various forms of activism. The workshops organised by J. often deal with women’s rights and the prevention of gender-based violence, addiction management and treatment, and the promotion of constructive individual expression among the youth.

M. runs her home garden in the neighbourhood of Manitas, which is located in the southeast of the city in the district of Ciudad Bolívar. This settlement developed informally as a result of the constant fluxes of immigrants that have been reaching the city from the countryside; the newcomers settled on the steep hills that surround the Tunjuelo river and created a densely populated neighbourhood, characterised by rudimentary buildings with exposed brickwork and winding roads that are hardly accessible by public transport, which is the reason why a cable car infrastructure servicing three stations was recently installed in the area.

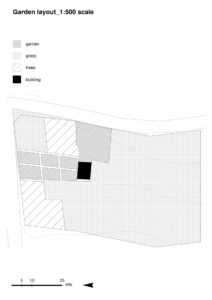

M.’s garden is located at five minutes’ walk from the Manitas cable car station, in a 25×50 m allotment in the premises of a “quebrada”, a ravine formation typical of the Bogotá area. M. started her garden about 18 years ago to provide for herself and her children, while taking care of the area surrounding the quebrada, which at the time was a dumpsite; some areas of M.’s garden are part of the quebrada, which explains the remarkable dimensions of this garden. In spite of her contribution to the environmental recovery of the area, over the years M. has been facing eviction threats from the local water authority, as quebradas are protected areas by Colombian environmental regulations and her activity was deemed as illegal.

Despite these pressures, M. has maintained her intent, creating a lush garden in which she grows food for her subsistence (albeit she sometimes gifts it to the neighbours), and ornamental plants of various kinds. The garden is not fenced, and M. has complained about how pots have sometimes been stolen by the local recyclers, which is why she now prefers to employ plastic bags as containers for her plants. When it doesn’t rain, she waters her garden with water from her house, through a hosepipe that arrives directly in the garden. Although her garden has no direct social or commercial purpose, M. is a local leader in the Manitas community, often engaged in activities aimed at implementing the sustainable development and social cohesion of her neighbourhood; this suggests that even if she does not manage a physical space for the community, her home garden fulfils a symbolic function of representation for urban agriculture in Manitas. Furthermore, M.’s ecological vocation also has economic implications, as she from time-to-time sells bags woven with recycled plastic and sauces produced with vegetables from her garden.

“Huerta villa Ines” is a community garden built within the premises of a JAC (Junta de Accion Comunal) community building in the district of Puente Aranda. Conversely to other parts of the district, the Villa Ines neighbourhood is particularly green due to the presence of the Santa Águeda park, which covers half of its area. This residential neighbourhood is of medium socioeconomic status (with a social index stratum of 3). The buildings are low in height and have a neat appearance, with plastered façades or decorative “ladrillos”. This section of the district does not face any main arterial roads, unlike those presented in the other case studies, which contributes to its more peaceful and tidy appearance.

JACs are community action boards created by groups of citizens who want to address issues that have arisen in their neighbourhoods. In Bogotá there are more than 20,000 of these non-profit community organisations, with their own legal status and assets. The municipality provides community halls and spaces on public land to JACs that apply for a physical location to host their activities. This is the case of the citizens’ group that created “Huerta Villa Ines”, in the eponymous neighbourhood.

This garden was founded to improve the aesthetics of the space surrounding the JAC community hall, which was full of debris from the construction of the building. Technicians from the Botanical Garden were contacted to assist the community in the planning and start-up of this garden. The managers of the site understood the food production potential of this space and began to engage in workshops provided by the Botanical Garden to learn agricultural techniques. This garden thus became both a place of food production, social cohesion, and environmental education.

The community garden currently comprises 22 beds of 0.8X 3.22 m plus a composter of 1 m3 that employs the “paca digestora” technique. The garden also includes a tool shed with a vermiculture area (measures of shed: 2.10x 4.2 m) and a line of fruit trees (5.8x 1.5 m). Irrigation is delivered through three rainwater collection tanks (3x 2000 litres each) that feed into a roof reservoir (1 x 1000 litres) from where the irrigation network spans. All the ameliorations to this site were achieved through the awarding of funds for a project proposal made by this active group of neighbours. It is worth noting that the safety of the area is ensured by the fencing that runs around the property perimeter. The produce of the garden is divided between the participants, a group of elderly ladies from the surrounding area, who also engage in environmental training courses, recycling and awareness campaigns at schools and cultural group activities. Finally, this garden collaborates with the HuertoCircuitos network of gardens in Puente Aranda, already presented in other case studies (CS3,4,7,8).

The district of Alaska is located at the edge of Bogotá’s urban territory in the Suba district, which covers the north-west of the city. Although it is only a few kilometres away from the Portal Suba terminal of the BRT Transmilenio service, this area has strong rural features. Separated from the more urbanised areas by the “Humedal de la Conejera” wetland, the Alaska neighbourhood develops around the main street (Carrera 111), connecting the city to the peri-urban area, where florists, golf courses, boarding schools and farms alternate seamlessly. The focal point of this low income neighbourhood (with a Social Stratum Index of 2) is the Corpas University Hospital, whose presence has led to the establishment of numerous cafés and bars for medical personnel in its vicinity. Entering one of the side streets of Carrera 111, we take a dirt road that runs alongside a boarding school and leads us to a series of enclosed farm fields, where our case study is located.

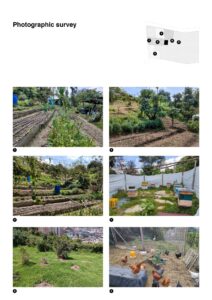

Seven years ago, the owner of this land was looking for a family that would look after his farm, which had been abandoned for several years. M.I. used to run a bar nearby and was growing tired of dealing with drunk customers. Given her rural origins, she decided to turn to urban agriculture to provide for her family; she proposed to the owner of the farm to become business partners, whereby she would have given him 50% of her earnings in exchange of the free occupation and use of his farm. After cleaning the land from debris and waste, M.I. and her daughter A. started cultivating the land, but soon realised they needed more specific knowledge to yield the most out of this garden.

They subsequently applied to receive trainings and support by the Botanical Garden, and they were assisted and included in their dedicated market networks. In her orchard of about 600 sqm M.I. grows leafy greens, fruit trees, medicinal herbs, various kinds of potatoes and cabbage. She keeps rabbits, chickens, cows and geese and has a water pond that supplies the whole area for irrigation. Maria Isabel stated that she does not employ artificial fertilisers or pesticides, thus making the produce and products from this garden organic. Together with five other gardens (CS14 being one of them), this garden is included in one of the agroecological routes inaugurated by the Botanical Garden to encourage ecotourism around urban and peri-urban agriculture, support the trade of local products, generate economic benefits for farmers and consolidate urban gardens as actors for environmental education.

This case study recently took part to the programme “Mujeres que reverdecen” (women who thrive again), organised by the Botanical Garden, in which women from vulnerable social groups work in urban farms to learn skills to emancipate themselves.

J. is a qualified forest engineer who, when faced with scarce employment possibilities within his sector, decided start farming the plot of land in front of his parents’ house, located between the Salitre and Santa Maria neighbourhoods within the district of Suba. The Salitre area is located at the bottom of the Suba hill, which in this area is called “La Conejera”, and is characterised by social housing and workshops. Conversely, the Santa Maria neighbourhood designates the area at the top of the hill, where we find luxury single-family villas. It is possible that La Conejera hill was initially a luxury residential area outside the city. With the rapid expansion of Bogotá over the last 60 years, all areas around the hill have been occupied by low-value housing, given its distance from the city centre. This would explain the considerable difference in the social stratum of these two areas (Salitre has a Social Stratum Index of 2, while Santa Maria’s is 4).

Our case study is located along the hillside of La Conejera, in the transition zone between these two realities. To reach it, we take a side street departing from the main road that crosses the Salitre neighbourhood, passing through workshops to reach a dirt road that leads to modest houses. Taking a steep road that climbs the hillside between informal housing and green meadows, we arrive at the entrance of the “Cobà” garden.

The site has an area of 1250 sqm and is built on a sloping terrain that has been terraced to improve its stability and facilitate agricultural activities within it. From the entrance gate, we walk along the central terracing for its entire length, until we reach a covered area used as a tool shed. A second shed is present on our right, while behind this, going down the hillside, we find several fruit trees. If we continue beyond the central tool shed, we encounter an area used for animal husbandry. Finally, in the southernmost part of the site, there is an area for breeding bees.

Crops vary from fruit trees to herbs and leafy greens. This urban farm also breeds various animals, such as chickens, geese, cows, bees. Irrigation is done through rainwater harvesting and the local supply network; J. has been meticulous in estimating his water consumption and consequently regulating the amount of used water. Although J. did not take part in the workshops organised by the Botanical Garden, he has attended several university courses to learn how to improve the productivity of his garden, which he only fertilizes organically. Parallel to urban agriculture, J. also took on the production of honey, which is traditionally practiced in this area, by restoring the beehives initially created by his grandfather and currently managed by his father, which is why J. called his garden “Cobà: the home of bees” (according to him the word Coba translates into “mossy water” in Mayan language). This garden is included (together with CS13) in one of the agroecological routes created by the Botanical Garden to encourage ecotourism and knowledge about more sustainable lifestyles. Similarly to CS13, this garden is taking part to the mentoring programme “Mujeres que reverdecen”, which aims at empowering vulnerable women.

Huerta “As.Chircales” was born 15 years ago in the Socorro neighbourhood, within the district of Rafael Uribe Uribe. Before the city expanded southwards, this area was used as a site for the extraction and processing of building materials. This is where the famous “ladrillos” bricks, which make up the façades of many buildings in Bogotá’s upper-class neighbourhoods, came from. The clay extracted from the hills surrounding this neighbourhood was moulded in bricks and baked in on-site kilns (which in Spanish are called “chircales”). During Bogotá’s expansion, rural immigrants settled mainly in the southern parts of city, considered to be of lesser value and therefore still occupiable. The landscape of Socorro bears the signs of this uncontrolled exploitation, with scarred hills covered by informal settlements, barren public parks, surrounded by a demised built environment.

When the city council of Bogotá declared illegal the manufacturing of bricks in kilns on environmental and geological grounds, A.’s family, who had been involved in this activity for generations, decided to turn the kiln site near their house into a garden. The initial intent was to create a beautiful space with ornamental plants, but the orchard quickly started producing enough to support A.’s family of six. As years passed by, the garden became more and more a reference point for the whole neighbourhood; A.’s family decided to create an association for the promotion and development of former kiln sites and currently their garden hosts a program featuring several social activities for the local youth.

The garden is created in the earthwork space between A.’s family home and the hill from which the clay was extracted to produce the bricks. From a small door at the end of a courtyard surrounded by informal-looking houses on the side of Diagonal 97, we climb a steep flight of steps lined with plants and shrubs. We find ourselves in front of a small veranda with benches surrounded by a small garden. On our right side, a walkway leads to a chicken coop and toilets. To our left, we find a self-built counter with an open-air kitchen, used by A.’s family to prepare meals and snacks for the young guests of this educational garden. Continuing to the left we find a community hall paved with the last bricks produced by the kiln, covered by a sheet metal canopy. Beyond the community hall, the garden expands into three sectors: an area with a fake well and concentric flowerbeds featuring herbs, an area with flowerbeds bordered by water-filled bottles featuring various vegetables, and a composting area. At the side of a water collection tank, behind the community hall, we descend to the lower level of the garden, where A. is setting up a greenhouse. Throughout the garden we encounter plaques and signs with positive messages inviting visitors to pursue a sustainable lifestyle.

Every Saturday children and adolescents from the neighbourhood gather at this community garden to learn about sustainability through educational gardening, recycling, food waste transformation, community events, animal husbandry, and cooking. Through these activities these children become promotors of sustainable lifestyles within their families thus contributing to the dissemination of social and environmental practices. This garden offers several services, such as the consolidation of local social networks and the protection of vulnerable subjects (such as children) from the influences of gangs, the implementation of recycling initiatives that have significant impacts on the neighbourhood, and the promotion of ecotourism models. The garden has steady relations with the Botanical Garden and benefits from their workshops and equipment supply.