Community-based volunteering in response to COVID-19:

The COV-VOL Project

PROJECT FUNDED BY: The NIHR Applied Research Collaboration (ARC), Kent, Surrey and Sussex

AUTHORED BY:

Dr. Julie MacInnes

Professor Patricia Wilson Rebecca Sharp

Professor Heather Gage

Dr Bridget Jones

Kat Frere-Smith

Dr. Vanessa Abrahamson

Tamsyn Eida

Sabrena Jaswal

January 2021

Introduction

In response to pressures on services, staff shortages and the number of vulnerable, older people required to self-isolate due to COVID-19, there has been an unprecedented response both in terms of requests for volunteers and also those signing up to offer support.[1] This mobilisation has been through nationally co-ordinated efforts, such as the GoodSAM platform[2] powering the deployment of volunteers for the NHS (in partnership with the Royal Voluntary Service) and other national charitable organisations, but also independent community groups supporting their local area. Despite evidence of the positive impact of volunteering[3], a previous study (OPEL)[4] identified significant concerns around community volunteering, including liability, health and safety, organisation and support, and risks to organisational reputation. The COV-VOL project addresses the following research question:

How can a community-based volunteer workforce be rapidly and safely implemented, and what is their impact on providing support for self-isolating and vulnerable older members of the community during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Methods

The study used a qualitative mixed methods approach. First, we conducted a rapid evidence review of published articles which addressed community-based volunteering in support of older people. We also sourced organisational documents on policies and procedures from Voluntary, Community and Social Enterprise (VCSE) organisations. We then conducted 88 semi-structured, telephone interviews with health and social care (H&SC) practitioners (12), volunteer organisers (25), volunteers (26) and older people in receipt of volunteer services (25), across the Kent, Surrey and Sussex region. The data were analysed thematically in order to identify key themes to support practice and policy-makers in ensuring the sustainability of the voluntary sector as a valued partner in our health and social care system.

Findings

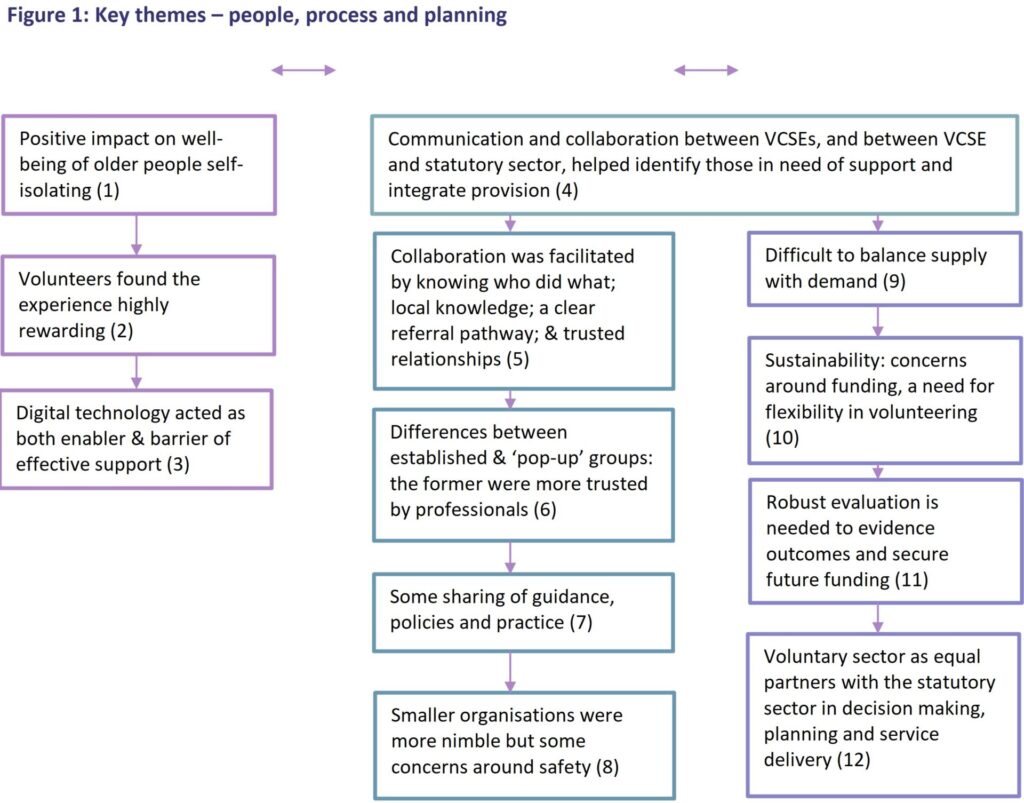

The following twelve key themes were identified (Figure 1):

Personal perspective |

1) Volunteers had a significant, positive impact on the well-being of older people self-isolating at home during COVID-19:

“I’d be absolutely stymied – I’d be in a right old pickle – I’d be forced then to go out to the supermarket and quite possibly get the virus” (Recipient, Male, 75)

“Its really important to say that the volunteers have been extraordinary and they have done something truly amazing…its made a massive difference to people’s lives…that army of people making 150 calls every week” (Volunteer Organiser)

“It’s been a great relief. To know there was a backup…really we just need to applaud them. They’re all volunteers. They’ve been so helpful and they have day jobs and families” (Recipient, Female, 76)

2) Volunteers described their roles as highly rewarding, contributing to their own sense of well-being and mental health:

“I feel I have benefited hugely…this is something I really wanted to do and I feel good about myself which sounds very self-congratulatory…I feel I am doing something for somebody else and I like that feeling…I find it very relaxing and therapeutic” (Volunteer, Female, 69)

3) The use of digital technologies was both an enabler and barrier of effective support. Communication was facilitated by online platforms such as Zoom. Conversely, a significant ‘digital divide’ between those older people who were able to use technology and those who were not, was highlighted:

“A student in, say once a week, to tell you things about mobiles and computers because the people I know have a crying demand for that – some don’t know a nything about it…and it will give you the contact with younger people. The lady [at the clinic] said, ‘ do Zoom’, and I said ‘what is Zoom – I’d never heard of it…it would be a great help for so many of us” (Recipient, male 82)

Process and Governance

4) Communication and collaboration between the VCSE organisations themselves and between Health and Social Care organisations, including local authorities, were key to identifying gaps in provision and avoiding duplication:

“We’re catching the people who are falling through the cracks and aren’t supported by the others” (Volunteer Organiser, local neighbourhood group)

5) Collaborative working between voluntary organisations and health and social care providers was facilitated by a shared understanding of what VCSE organisations could provide, robust mechanisms of referral between organisations, local knowledge of what support is available in communities, and trusted relationships.

6) There were perceived differences between established VCSE groups and so-called ‘pop-up’ groups who came together in response to COVID-19, primarily in terms of trust and governance arrangements. This was demonstrated by H&SC professionals being most likely to ‘signpost’ to established groups with well-developed audit, monitoring and governance processes and procedures in place, rather than newly generated schemes:

“I have got a little bit of concern, because I don’t know them, I don’t know what their regulation is like. We have to be a little bit more mindful” (Primary Healthcare professional)

7) There was some sharing of guidance, policies and practice through informal networks in order to spread learning and share ‘best practice’. Resources were also accessed from national organisations (e.g NCVO).

8) VCSE organisations were able to respond quickly to need due to fewer complex operational processes and procedures such as DBS checks. However this nimble way of working was balanced against concerns around safeguarding for both the volunteers and recipients:

“Quite often in the voluntary sector we can spend an awful lot of time planning and developing a project idea, and our telephone befriending service was set up in a couple of weeks in lockdown, whereas normally that would take 3-4 months. And it was put together quite well…so it does make you think what would we normally be doing in those 3-4 months! We must have wasted a lot of time in the past as a sector…we need to realise it’s okay to just take a gamble and just do something because it feels like it’s the right thing to do” (Volunteer Organiser)

“The fact that they [other organisations] didn’t do DBS checks on anybody, I thought was shocking” (Volunteer Organiser)

Forward Planning:

9) There was often a mismatch between volunteer supply and demand. Early on in the pandemic there was an excess of volunteers, whilst later, although demand for support decreased as government restrictions were lifted, there was a greater drop in the number of volunteers as people returned to work. Demand for support was variable and highly context dependent:

“I wonder how many people are in a similar position to me? – the altruism may have waned, the commitments may have increased, the ways to spend time have also increased” (Volunteer, Female, 32)

10) There are lessons to be learnt in terms of sustainability during the restart and recovery phase of the pandemic and beyond, in terms of i) the financial stability of VCSE sector as a whole and ii) maintaining the supply of volunteers.

a) Financial support for organisations was of significant concern.

“There is going to be a second wave and there is an expectation that the VCS will react in exactly the same way…but more than half of the VCS sector do not have the funding to do the same thing again, and they will go under before that” (Volunteer Organiser)

b) Factors that enhanced sustainability of the volunteer workforce were identified as: the opportunity to volunteer flexibly in terms of both time and choice of volunteering activities; having support from the VCSE organisation such as being able to share the emotional burden and raise concerns; understanding and supportive employers; and the development of strong personal relationships with recipients through careful ‘matching’ by the VCSE organisation.

11) Few voluntary organisations had a robust strategy for evaluating their services, which may have an impact on their ability to secure ongoing funding. Often, volunteers were also unable to describe the extent to which their support was effective in meeting the needs of older people .

12) Given the response of the voluntary sector to COVID-19, voluntary organisations want to be given a voice within integrated H&SC systems, with the opportunity to contribute as equal partners in planning, decision-making and service delivery.

Conclusion

Volunteers have made a significant, positive contribution to the health and wellbeing of older, self-isolating people during COVID-19. The pandemic has highlighted the importance of VCSE organisations as partners in health and social care systems. There is a now a unique opportunity to raise the profile of these organisations, putting them on an equal footing with statutory health and social care services in terms of strategic planning, decision-making and service delivery. This study identifies key themes which, going forward, are essential to support the on-going sustainability of both the volunteer workforce and the VCSE sector.

[1] Jones R (2020) UK volunteering soars during covid crisis. The Guardian. 26th May

[2] Royal Voluntary Service/NHS (2020) GoodSAM: NHS Volunteer Responders. Available at: https://www.goodsamapp.org/assets/pdf/GoodSAMNHSVolunteerinFAQs.pdf

[3] McGarvey A, Jochum V, Chan O, Delaney S, Young R, Gillies C (2020) Time well spent: volunteering in the public sector. VCVO

[4] Butler C, Brigden C, Gage H, Williams P, Holdsworth L, Greene K, Wee B, Barclay S, Wilson P. (2018) Optimum hospice at home services for end-of-life care: protocol of a mixed methods study employing realist evaluation. BMJ Open;8:e021192. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-021192