‘Invaluable in all cases of incontinence of urine, and… indispensable for long journeys by railway!’

The above quote comes from an advert published in 1882 for an intriguing device then sometimes referred to as the ‘travelling urinal’. In the nineteenth century, these urinals seem to have become a regular feature in contemporary newspapers and surgical catalogues, with different models developed and sold by instrument makers in places like London and Bristol. Though each urinal was either adapted for use by men or women, most models were formed of a long bag made with ‘solid vulcanised India-Rubber of the best quality’, which connected to a small reservoir that either sat in between the legs or fitted directly onto the penis. Adverts claimed that these urinals could be fixed to the body with a belt and hidden under clothing, and therefore ‘worn with great comfort, ‘without being perceived by anyone’. Prices also often varied depending on the model: one instrument maker sold their female urinal for 18 shillings and sixpence, whilst a male urinal was priced lower, at 15 shillings and sixpence.

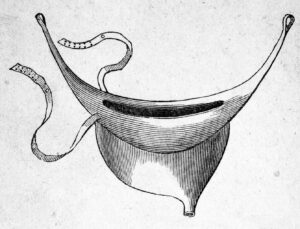

Credit: India rubber urinal for railway travellers, invalids etc.; winner of the Great Exhibition prize medal 1851. Wellcome Collection. Source: Wellcome Collection.

As the opening quote shows, by the late nineteenth century these devices were presented as a necessity for anyone wishing to partake in new forms of rail travel. Though travelling by train had made it possible for people to move across the country faster than ever before, some early train carriages were not equipped with toilets. As acknowledged by British physician J. Milner Fothergill in 1885, a travelling urinal was therefore ‘almost unavoidable in these days of fast trains, with long runs and brief stoppages’, particularly for ‘old persons and invalids [for whom] this haste is a trial’. However, the same urinals were also often specifically marketed as the solution for coping with incontinence of urine, both for those living with this condition but also those caring for them. These urinals were therefore in turn sold to the ‘Medical Profession, Unions, Infirmaries and Hospitals, [and] supplied on the Lowest Terms.’

These adverts arguably show how the development of the nineteenth-century travelling urinal was guided by the rise of rail travel but also the dynamic medical marketplace, giving us a fairly basic understanding of what these devices were and where they came from. But mysteries remain. It is much more difficult, for example, to definitively establish how these devices were used, who by, and moreover to appreciate the ways in which this was likely mediated by gender, race and class. As with many of the devices used to treat urine incontinence, in the past and the present, these urinals were marketed on how they allowed people with this condition to manage it privately and in secrecy; personal accounts of how it felt to use one whilst travelling, leaving the home or receiving care in bed in an institution, are therefore hard to find.

Do you know anything about travelling urinals and their history? Have you also seen them referenced in medical journals or periodicals, perhaps even in personal diaries or journals? If so, get in touch, we’d love to hear from you!