A few months ago, whilst skimming through an edition of The Medical Officer journal from July 1964, I found an intriguing advert for ‘Johnson’s underpads’. This was a new commercial product developed by the American pharmaceutical company, Johnson & Johnson, to help manage urine incontinence in the home. By absorbing ‘500 c.c. of water’, it was claimed that these underpads would not disintegrate when wet and would ‘minimise’ leaks of urine onto bed linen and clothes, thus addressing ‘laundry problems’. Made of ‘non-woven facing material’ that was ‘easy to dispose of’, these ‘soft’ pads also ensured ‘greater comfort for the patient’ and could be prescribed by local authorities via Section 28 of the National Health Service Act.

Source: The Medical Officer, 3 July 1964, xviii

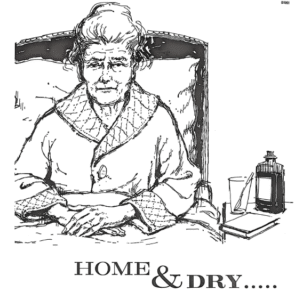

An accompanying sketch depicted an older woman sat upright in bed wearing a dressing gown, with her bony hands and long fingers folded in her lap. Her hair was pulled back in a bun with strands escaping from the sides, her face covered with wrinkles and brow furrowed in concern. A bottle of medication, an empty glass with a spoon and a book had been placed within close reach next to her on a bedside table.

This advert caught my attention for a couple of reasons. Firstly, I was interested by how it represented urine incontinence as a condition typical to old age, and secondly, in why this seemed to be gendered. Over the last months, I have explored the relationship between urine incontinence and old age through tracing the shifting medical discourses which surrounded the incontinent body in Britain over the period between 1870 and 1970. In the late nineteenth century, incontinence in old age was, somewhat paradoxically, seen by physicians as a consequence of retention. This was embodied in the enlarged male prostate and in pathological evidence of organic damage, tumours or bladder stones, and treated through surgical interventions, such as the catheter, which facilitated the controlled release of urine. These clinical, pathological and surgical techniques allowed physicians to develop contingent medical theories of urine incontinence through and in the older male body, with such leakiness becoming associated with age-related disease and decline. It was not however always easy for physicians to identify the causes of this ‘secondary affection’, which seemed in some older women to be linked to vague bodily signs such as a ‘pendulous abdomen’ or a history of hysteria, which were in turn less easy to treat.

But the meanings ascribed to leakiness in old age shifted in the early to mid-twentieth century, as incontinence became understood as a cause of bed-blocking and significant labour and laundry costs, and in turn as a focus of administrative, economic and medical concern in hospital provision for the ‘chronic sick’. As historians have shown, the majority of patients receiving such care were older women, whose bodies (and minds) became of medical interest and intervention to geriatricians seeking to make a case for their medical specialty within a health system poised to become the responsibility of the state. They pulled focus away from internal blockage, damage or disease in the body, towards the mind and to emotional upset caused by the neglect of older people, often women, in specific hospital and home environments, which were investigated by social workers and psychiatrists. Effective treatment and prevention now centred on ensuring that older people felt comfortable, happy and independent in these settings, and on controlling how they interacted with nurses and family members, who were also seen as responsible for their care in the way that a mother was for their child.

In this context, the disposable underpad emerged as a material alternative to the urinal, which had long been used to nurse older male patients in bed yet was less suited to women based on perceived anatomical differences and the risk of spillages. Seen to reduce shame and worry, as well as the labour of washing and replacing ‘soiled’ items, the underpad was invested with emotional and economic value from the perspective of geriatricians and became a vital aid to state-funded medical and nursing care, which by the mid-1960s was increasingly focused on bringing older people ‘home and dry’. As symbolised by the imagery of the Johnson & Johnson advert, we might also think of this as a model of care that hinged on a particular incontinent body, which was represented as old yet also childlike, depressed yet dependent, and arguably, as female.