‘Memoranda of my stricture’ by Michael Hughes, 1858: Thoughts on a Source

The patient is often an elusive historical figure. But as historians of medicine have long recognized, diaries, notes, memoirs and other records written by patients can aid the uncovering of different health regimes, diseases and their treatments at given points in time. ‘Memoranda of my stricture’ by Michael Hughes (1810-1886), a copper industrialist of St Helen’s, Merseyside, provides an unparalleled record of one well-to-do man’s struggles with the rather painful, socially embarrassing and emasculating disorder of urethral stricture in the mid-nineteenth century. Although little explored by historians, urethral stricture was both a complaint common to the nineteenth century (particularly among men) and an incredibly dangerous one. Some form of blockage or infection (including venereal) caused the urethra to narrow meaning that urine was retained in the bladder; this retention could be fatal.

Held at St Helen’s Archives as part of the Sherdley Estate papers, the estate Hughes had inherited from his father and where he lived for some of his life, Hughes’ 30-page memoranda provides a detailed account of his experience of stricture between March 1858 and August 1859 when aged 48. Hughes’ first entry highlights his concern about urinary flow: ‘I can not remember the time when my stream of water was a full natural size. It is probably nearly 30 years since.’ And while his unnatural ‘stream’ had long been a concern to him, as well as the fact that urine would trickle from him involuntarily, it was the complete retention of urine over a 24-hour period in February 1858 that made him seek medical treatment.

The fact that Hughes did not seek medical help before crisis point and had put up with his unnatural urinary flow for years is hardly surprising. Treatment for stricture consisted of the not-inconsiderably painful procedure of dilation; this involved passing long metal or rubber rods of varying shapes and sizes called bougies down the urethra and into the bladder, which, on removal, would allow the urine to flow and eventually stretch the urethra to ‘normal’ size.

Bougies in Catalogue of surgical instruments & appliances, aseptic hospital furniture and surgical dressings, etc., etc / manufactured and sold by S. Maw, Son & Sons. In copyright. Source: Wellcome Collection.

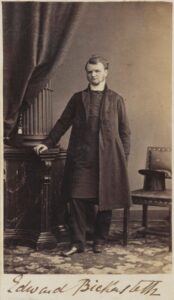

The first practitioner Hughes consulted, a surgeon local to St Helen’s who may have untaken dilation before but was certainly no specialist, gave him opium but was unable to pass any size bougie into his urethra. The subsequent 3am call to Mr Edward Robert Bickersteth (1862 – 1924) of Liverpool, a well-respected urological surgeon, again highlights the serious nature of the condition but also suggests the levels of discomfort and pain experienced by Hughes. Hughes reports that at 3.15am, Bickersteth was able to pass a bougie, size number 3, into the urethra and thus relieving the urine retention.

Edward Bickersteth

by Unknown photographer

albumen carte-de-visite, early 1860s

NPG Ax9613

Following this initial success, Hughes then recorded his twice weekly visits to Bickersteth’s private practice on Rodney Street, Liverpool, for urethral dilation. Across the next 18 pages of his memoranda and over the next two months, Hughes recorded the progress of Bickersteth (or ‘Mr B’ as Hughes begins to call him) and the varying ease or difficulty Bickersteth experienced in passing bougies of ever-increasing sizes. At times, it is clear that dilation led to Hughes experiencing great pain, inflammation and the release of bloody urine. But by mid-April, Hughes expressed delight that Bickersteth was able to pass a number 9 size bougie.

What made Hughes record his experiences of stricture and his frequent trips to Mr B? The intimate and painful nature of the procedure (as well as its possible links to venereal disease) has evidently led to a dearth of similar recorded experiences, particularly in this level of detail; others of course may not have had Hughes’ level of literacy. But individual instances of dilation are also pretty mundane, and the recording of such instances over a long period of time may not have been considered significant. However, Hughes meticulous records of each procedure in a memorandum, each written in a detached and medical style, are clearly not for anyone else’s benefit, but as a record for himself: he is learning from Mr B how to be his own surgeon.

On Saturday 22nd May, Hughes recorded that he ‘took out the number 9 myself for the first time,’ while being observed by Mr B. The following Tuesday, Mr B told Hughes to purchase two Symes’ bougies himself, the numbers 8 and 9, from Mr Young, Edinburgh’s surgical instrument maker. Hughes’ first attempt to pass his own number 8 failed on 29th April, but he was subsequently able pass numbers 8, 9 and 10. His inexperience in conducting the procedure on himself over the next few weeks evidently resulted in inflammation and thus Mr B was required again to pass the bougies. On 29th June, Hughes recorded that he passed the number 9 bougie into the bladder and that Mr B was present ‘and assisted me with his advice but did not operate at all.’ On 6th July, Hughes is confident that he no longer needs Mr B’s assistance as he can successfully pass his own bougies, although by the 15th, he visits Mr B again seemingly panicked about not being able to pass a number 10. Mr B calmed him down by telling him ‘that I might expect this to occur occasionally’ and that a general rule is ‘not to attempt a larger bougie when the preceding instrument feels tight in drawing out.’ Thereafter, Hughes’ memoranda turns into a 5-page list that repeats ‘I passed numbers 8, 9 and 10’ on a weekly basis until Sunday 8th May 1859. On this date, Hughes records his ‘first failure since leaving Mr B’s care in July 1858. I cannot give any sufficient reason for this,’ although he continues to blame his ‘own unskilful attempts.’ His attempt apparently succeeded on the Monday, whereafter he continued to conduct the procedure on himself on a weekly basis until August 1859. Hughes’ last entry in August records his final visit to Mr B, who considered him completely cured.

What can we make of Hughes memoranda then? It is clear that Hughes learned from Mr B how to become his own surgeon, demonstrating an interesting interplay between expert/non-expert knowledge and patient experience at a time when medical professionalisation and specialisation was taking off. It was clearly in Bickersteth’s financial interest to keep the financially-well off Hughes as his patient, but instead Bickersteth encouraged Hughes to purchase his own instruments and becomes skilled at ‘the operation’ himself at home. Given his excellent reputation as a urinary specialist, perhaps Mr B was overwhelmed by patient demand! But in this instance, not only does the patient’s experience not disappear from the medical encounter with increased medicalisation (as famously suggested by Nicholas Jewson among others) but it becomes integral to the patient’s eventual cure. Indeed, Hughes’ continual reference to Bickersteth as Mr B throughout suggests the friendly relations between practitioner and patient (although it was also easier to record too).

There are, no doubt, many more examples of self-operation – tooth pulling and boil lancing, for example. And there are other less detailed examples of self-dilation (see Inskip & Muir 2023 for an excellent analysis of the use of clay pipes as catheters in the nineteenth century); I’d be interested to know how others experienced it and how these experiences inevitably differed by class and gender. Is this lack of evidence the reason historians have long neglected such a procedure or indeed, any modern urinary disorder? The abundance of contemporary textbooks on the urinary system, and the bougies, catheters, dilators, irrigators, trocars, cystoscopes, lithotrites and all manner of other instruments aimed at their treatment that were both widely sold in the nineteenth century and that crowd the stores of medical museums throughout the world today suggest that this isn’t the case. Is it that historians simply find urinary disorders too uninteresting or unimportant? If so, why? Retention of urine was often fatal, and Hughes certainly considered his condition important enough to dedicate 30-page memoranda to it. Is it that urine and penises are too unsavoury and trivial to be subjects of foci? Likely. But I would like more historical attention paid to the messy, leakiness of the material body. It is after all this messiness that makes us human.